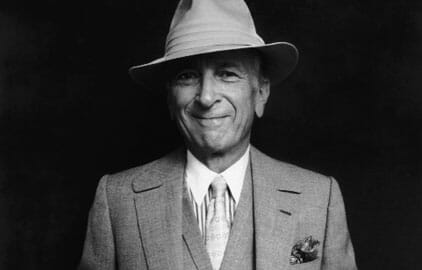

Gay Talese – A Writer’s Life

Other People’s Stories: A great reporter disappears from his own memoir

No one who’s ever published a book should review one, because empathy for the victim—the author, rather—undermines objectivity.

Suppose you’re renowned journalist Gay Talese. You’ll soon be 74 and your memoir, A Writer’s Life, will be published in April. At the very moment your proofs go out to reviewers, your wife the famous editor is buried up to her bifocals in the James Frey-memoir scandal, the first in a chain of breaking scandals that promises, at least, to re-introduce truth-in-labeling to the literary marketplace—humble truth, a porous levee against the blood-dimmed tide of mangy, redundant memoir threatening to wipe out literature altogether.

Talese is not the first author cursed by wretched timing and cruel coincidence; a friend of mine published the best book he ever wrote on Sept. 11, 2001. So I feel Talese’s pain acutely. And I swear I opened A Writer’s Life with high hopes. But it’s one of the strangest damn books I’ve ever read.

Talese provokes none of my usual prejudices. He’s not an autobiographer who experiences his own life as an intoxicating epic. If anything he’s the opposite, a celebrity mildly surprised he’s someone from whom the public might expect a memoir. He leaves the peculiar impression that he was tempted to write one but lacked the stomach for it.

Still, he’s hardly shy. When he needs help with a story in Beijing, Talese calls Henry Kissinger—no response—and the president of Nike, Philip Knight. But like many celebrated reporters, he ?nds introspection intimidating, and admits it. “I had no idea what my story was,” he writes. “I had never given much thought to who I was. I had always defined myself through my work, which was always about other people.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-