Before Seeing Wicked, Read Gregory Maguire’s Very Weird, Very Adult Oz Novels

The long-awaited big-screen adaptation of Wicked, the multi-million-selling Broadway musical, finally arrives on our screens this month (or, at least, the first half does.) Cynthia Erivo and Ariana Grande star as the witches bad and good who get to tell their side of the story that was omitted from L. Frank Baum’s beloved Oz novels. Wicked is perhaps the single most iconic musical still running on Broadway following the closure of The Phantom of the Opera. It enthralls musical die-hards and casual visitors alike with its showy production values, series of earworm-worthy tunes, and a central narrative about female friendship, love, and finding your true self. One could argue that, for the youngest generation, the story of The Wicked Witch of the West is more thoroughly defined in their imaginations by Wicked than The Wizard of Oz.

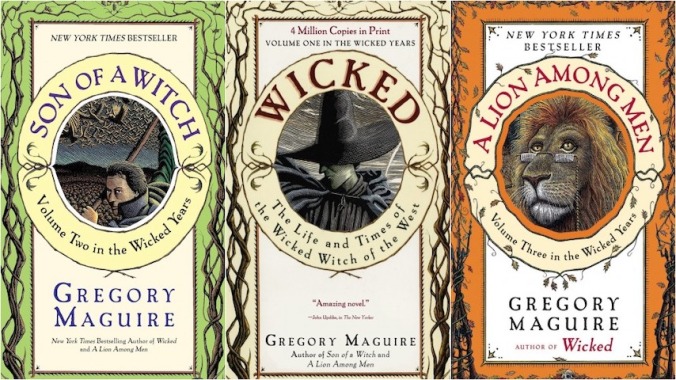

Creatives have plundered Baum’s work for decades, finding ways to adapt, reinvent, or straight-up rip off the Oz mythos. Wicked, however, isn’t technically a Baum adaptation. It’s based on a very strange and very serious adult novel that used the Oz story as a platform to explore the origins of human evil. That book is also a far pricklier creature than the toe-tapping tale of empowerment that’s still running on Broadway.

Published in 1995, Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West was never intended to be read by kids. Author Gregory Maguire was a children’s author who had begun to think about issues of good and bad while watching news coverage of both the first Iraq war and the murder of baby James Bulger by two pre-teen boys. He wondered if evil was something one was born with or if it was created through circumstance. Using this age-old conundrum as his foundation, he turned to Baum’s Oz books, which he was a lifelong fan of, to further tease out his ideas. Why was the Wicked Witch so wicked, and did she get a bad rap from young Dorothy Gale and her friends?

Wicked is a very weird book. It’s a dense political thriller about an eco-terrorist who becomes the patsy of a corrupt government trying to avoid a civil war incited by their enforcement of an Apartheid system. And yes, it has witches and munchkins and talking lions.

The witch Elphaba (named after the author—L. Frank Baum = ElPhaBa) is a green-skinned daughter of an alcoholic who was date-raped. She was raised by a self-loathing bisexual preacher alongside her sister, who becomes the mystical version of Pat Robertson. At university, she meets Glinda, the future good witch of the north, and they become embroiled in a plot to help the Oz government retain its iron grip on the masses. Elphaba, however, revolts, calling out the two-tier system of inequality that the nation’s anthropomorphic animals live under. This leads to her being declared an enemy of the state and their convenient scapegoat.

The Elphaba of the book is a far pricklier protagonist than the one in the musical, who is mostly an outsider who finds herself through love, a cool BFF, and a banging end-of-act-one song.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-