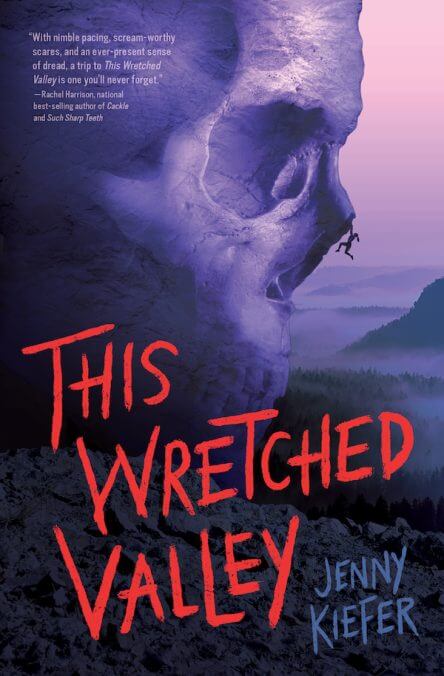

The First Chapter of This Wretched Valley Promises Chilling Wilderness Horror

The great outdoors is certainly beautiful, but its pristine vistas and lush forests can often hide dark and frightening threats underneath. And Jenny Kiefer’s upcoming horror novel This Wretched Valley leans fully into the scariest aspects of the wilderness—the sheer terror of the unknown.

Described as perfect for fans of Yellowjackets and the horror novels of Alma Katsu, This Wretched Valley is inspired by the infamous Dyatlov Pass incident, which saw a group of Soviet mountaineers freeze to death in the Ural Mountains in 1959 under the sort of mysterious and inexplicable circumstances that inspired conspiracy theories for decades afterward. (Several had skull injuries, others were missing eyes, some were naked and there were traces of radioactivity on their clothes.) This story is set in the uncharted woods near Kentucky’s Red River Gorge where four twentysomethings set out to find an unscalable rock formation, but what the group discovers is something much darker—and a whole lot bloodier.

Here’s how the publisher describes the story.

This is going to be Dylan’s big break. Her friend Clay, a geology student, has discovered an untouched cliff face in the Kentucky wilderness, and she is going to be the first person to climb it. Together with Clay, his research assistant Sylvia, and Dylan’s boyfriend Luke, she is going to document her achievement on Instagram and finally cement her place as the next rising star in rock climbing.

Seven months later, three bodies are discovered in the trees just off the highway. All are in various states of one body a stark, white skeleton; the second emptied of its organs; and the third a mutilated corpse with the tongue, eyes, ears, and fingers removed.

But Dylan is still missing. Followers of her Instagram account report seeing disturbing livestreams, and some even claim to have caught glimpses of her vanishing into the thick woods, but no trace of her—dead or alive—has been discovered.

Were the climbers murdered? Did they succumb to cannibalism? Or are their impossible bodies the work of an even more sinister force? Is Dylan still alive, and does she hold the answers?

This Wretched Valley won’t hit shelves until January 16, 2024, but we’re thrilled to be able to give you a first look at the book’s first chapter right now. (Which, let’s just say from the jump is not for the faint-hearted.)

![]()

OCTOBER 2019

Lacy Baugher Milas is the Books Editor at Paste Magazine, but loves nerding out about all sorts of pop culture. You can find her on Twitter @LacyM

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-