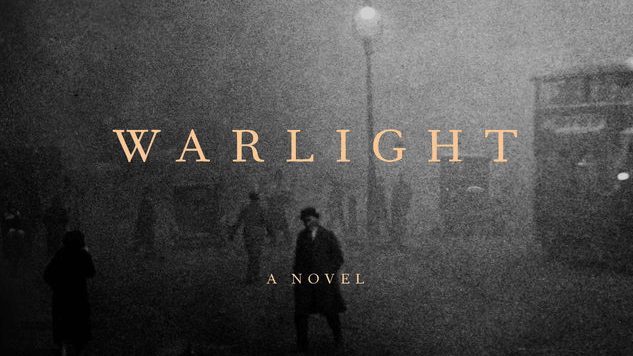

The Cinematic Appeal of Michael Ondaatje’s Warlight

Alicia Huberman (Ingrid Bergman) is in a sour mood. Hungover, embarrassed, harangued by American agent T.R. Devlin (Cary Grant), the daughter of a newly convicted Nazi spy stirs from her latest bender with the nauseous spin of the camera, its Alka-Seltzer twirl. So it’s no surprise she resists Devlin’s proposal: to infiltrate a ring of Nazi industrialists in Rio by seducing one of its leaders and then to “smoke them out.”

She’ll relent, by degrees—first as Devlin plays a recording of Alicia arguing against her father on America’s behalf, and later as she falls in love with her handler—but here, in the opening stages of Alfred Hitchcock’s Notorious (1946), she bears the burden of the cynic, confident that no motive is pure. “I don’t go for patriotism, or patriots,” she snipes. “Waving the flag with one hand and picking pockets with the other, that’s your patriotism. Well, you can have it.”

Though it’s absent the glamour of Bergman swanning through grand salons and palatial foyers, Michael Ondaatje’s absorbing new novel, Warlight, inhabits much the same milieu: the demimonde of hustlers, informants, soldiers and spies that the filled the cracks left by an interminable conflict. Its protagonist is Nathaniel, a researcher for the U.K.’s Foreign Office reflecting on his wartime childhood from the relative safety—that’s the word he’d use—of the late 1950s. Abandoned by their mother during the Blitz, Nathaniel and his now-estranged sister, Rachel, fell under the care of men with names that might’ve been plucked from one of Hitchcock’s prewar capers: the Moth, their mysterious third-floor lodger, and his friend the Darter, a former boxer turned two-bit criminal with a series of alluring girlfriends. Through his description of life in the shadow of the Second World War and his investigations in the National Archives, Nathaniel learns that his mother was a British government agent in those years of transition, though he never quite satisfies his yearning to know the reasons for her departure. It’s certainly not so pure as fealty to king and country: Warlight doesn’t go for patriotism, either.

Though it’s absent the glamour of Bergman swanning through grand salons and palatial foyers, Michael Ondaatje’s absorbing new novel, Warlight, inhabits much the same milieu: the demimonde of hustlers, informants, soldiers and spies that the filled the cracks left by an interminable conflict. Its protagonist is Nathaniel, a researcher for the U.K.’s Foreign Office reflecting on his wartime childhood from the relative safety—that’s the word he’d use—of the late 1950s. Abandoned by their mother during the Blitz, Nathaniel and his now-estranged sister, Rachel, fell under the care of men with names that might’ve been plucked from one of Hitchcock’s prewar capers: the Moth, their mysterious third-floor lodger, and his friend the Darter, a former boxer turned two-bit criminal with a series of alluring girlfriends. Through his description of life in the shadow of the Second World War and his investigations in the National Archives, Nathaniel learns that his mother was a British government agent in those years of transition, though he never quite satisfies his yearning to know the reasons for her departure. It’s certainly not so pure as fealty to king and country: Warlight doesn’t go for patriotism, either.

In this, Ondaatje draws on the tradition of Graham Greene, the writer of one of the most delightfully jaundiced films to come out of Europe after the war: The Third Man (1949). Directed by Carol Reed, the film stars Joseph Cotten as Holly Martins, an author of dime-store Westerns who alights for occupied Vienna at the behest of his old friend, Harry Lime—only to find himself at his poor pal’s funeral, still holding his small valise. Holly soon embarks on an investigation of his own, becoming smitten with Harry’s girlfriend, Anna (Alida Valli), and tangling with a member of the British Army Police (Trevor Howard) in the process. While he ultimately discovers that reports of Harry’s death have been greatly exaggerated, the plot is almost incidental.

That the details are interchangeable might, in fact, be the point. As Ondaatje perceives, following Hitchcock, Greene and Reed, the postwar period—world-weary, urbane, slightly seedy—is defined by this dissolution of boundaries, this globalization of grief. Remix the particulars—their wine cellars and skeleton keys, fingerprints and cuckoo clocks, smuggled greyhounds and empty flats—and the fog of war scarcely lifts. In these stories, the postwar setting is signaled by mood as often as it is the time or place, a setting in which “peace” is a brief disruption in hostilities and every city is its own Vienna.

On a thematic level, the heart of Warlight is its reconsideration of this postwar moment, a mystery at once among and about the “revisionist histories,” as Nathaniel explains, that were “the repercussions of peace.” In the course of his work—the assessment, classification and, in some cases, destruction of documents related to the British war effort—he learns that the embers of conflagration kept glowing long after V-E Day. They’re fanned by operatives, including his mother, working from one end of the continent to the other—actions subject, via waves of “apocalyptic censorship,” to erasure.

For Ondaatje, though, reclaiming the period also means reconstructing it, and one of the foremost pleasures of Warlight is its cunning spin on the postwar aesthetic. For one, its chronological slipperiness captures the nebulousness of the term “postwar” itself. Though there are firm points of demarcation—1945, in the novel’s first sentence, when the Moth and the Darter come into Nathaniel’s life; 1959, in the first sentence of Part Two, when Nathaniel purchases a home in the village where his late mother had lived—Warlight is full of quiet shifts between and within multiple periods of action. For another, Ondaatje laces the novel with the sort of dramatic situations in which one tends to picture matinee idols: a chase sequence on a London bus, an assassin approaching a remote cottage, a chess match at the opening night of Bellini’s Norma. There’s even brief reference made to a writer from one of the colonies with an unpronounceable name, as if Ondaatje had cast himself in one of Hitchcock’s cameos.

If these fillips of invention are reminiscent of Notorious—with its elongated zoom in on Alicia’s hand from the top of a spiral staircase—or The Third Man—with its canted compositions and impossible silhouettes—they’re also self-aware gestures at “postwar” film and fiction as both a reflection of the era and a genre in its own right. “I suppose there are traditions and tropes in stories like this,” Nathaniel admits in the opening pages. “Someone is given a test to carry out. No one knows who the truth bearer is. People are not who or where we think they are. And there is someone who watches from an unknown location.”

But such stories’ most essential trope isn’t the setting, or the international cast, or the set pieces; it’s the sense of depletion, of illness, of bone-deep fatigue that suffuses so much postwar art, resigned to the faint notion that war cracks us open but cannot heal. When Holly Martins finally comes face to face with Harry Lime (Orson Welles), after all, the latter justifies his sale of deadly, diluted penicillin by sounding much the same note as Alicia Huberman does. “Nobody thinks in terms of human beings,” Lime sneers from a Ferris wheel, pointing out the human specks on the ground below. “Governments don’t. Why should we? They talk about ‘the people’ and ‘the proletariat.’ I talk about ‘the suckers’ and ‘the mugs.’ It’s the same thing. They have their Five-Year Plans, and so have I.”

The closest Warlight comes to a firm definition of “postwar” so poignantly echoes Alicia Huberman, Harry Lime,and the other shadowy figures of the era’s films that it deserves to be quoted at length:

“It was a time of war ghosts, the grey buildings unlit, even at night, their shattered windows still covered over with black material where glass had been. The city still felt wounded, uncertain of itself. It allowed one to be rule-less. Everything had already happened. Hadn’t it?”

As long as I’ve been enraptured by Alfred Hitchcock and Carol Reed, by the Italian neorealists and the Germans in Hollywood, by the French noirs of the 1950s and the Ealing comedies, I’ve thought there must be something to my affinity for the period—some connection among these disparate stories to the flag-waving, pocket-picking, imperfect present in which I came of age. I had never found a term that might encompass all the films I love the most, or, for that matter, the perpetual “after” in which I first encountered them. Until reading Ondaatje, that is.

Warlight is the color of the postwar cinema and, indeed, the temper of our times.

Matt Brennan is the TV editor of Paste Magazine. He tweets about what he’s watching @thefilmgoer.