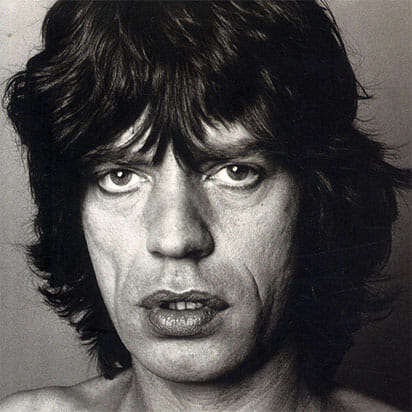

Mick Jagger by Philip Norman

Still Searching For Satisfaction

Mick Jagger – written by Philip Norman, who has previously authored books about John Lennon, Buddy Holly, Elton John, and the Rolling Stones — adds yet another entry to the seemingly endless chronicles of the Stones. 2012 marks the group’s 50th anniversary, and there may not be another musical entity in history that has been as well documented.

Over the years, directors have put together countless documentaries, from all stages of their career – Gimme Shelter, depicting their famous Altamont concert, where four fans were killed; Cocksucker Blues, grainy footage from famous photographer Robert Frank that floats around the Internet displaying the Stones at their most hedonistic; Shine A Light, where Scorsese shows the Stones in post-82 mode (1981 being the year of their last good album, Tattoo You) playing to baby-boomers with booming bank accounts. This year added two more entries to this list, Charlie Is My Darling, which shows the band on tour in Ireland back in 1965, and Crossfire Hurricane, out recently on HBO, which contains scenes of the band in various decades.

We also have the photo books, full-band histories, cultural accounts of the ‘60s and ‘70s, fact books, Life magazine compilations, and Playboy interviews. And of course biographies and autobiographies, a few of which focus on the Stones’ less-famous members: Brian Jones, one of the founders, who died in 1969; Charlie Watts, drummer; Bill Wyman, bassist; Ronnie Wood, the band’s third lead guitarist. Naturally, the lion’s share of the bios focuses on the Stones’ two heads—“the glimmer twins”—guitarist Keith Richards, who famously works with great success to look more like a member of the undead every year, and lead singer Mick Jagger, who attempts with less success to try to maintain his youthful, swinging-fashionista persona.

Jagger and Richards have been at odds frequently throughout their careers. In that life-long competition, Richards’s score (point total, not the kind of score that preoccupied him for much of his life) went up in 2010, when he released his much-lauded autobiography, Life, which often described Jagger as a vain primadonna with less talent than his guitarist. The people in the Jagger camp may have noticed this and worried their boy was falling behind. They increased their Mick production as a result; a quick search on Amazon indicates that four new Jagger-centric books came out in 2011 and 2012, including this one.

Author Norman suggests that Jagger cultivates a slippery blandness with the media that allows him to avoid “months boringly closeted with a ghostwriter, or answer[ing] awkward questions about his sex life.” (According to Norman, Jagger put together a draft of an autobiography in 1983, but the “manuscript was pronounced irremediably dull by the publisher and the entire advance had to be returned”.) Thus, since Jagger has bowed out, either unable or purposely unwilling to talk about himself, it becomes Norman’s duty to write this book.

Mick Jagger begins with a series of hyperbolic and hagiographic statements. Norman writes that “despite all the proliferating genres of ‘new’ rock ‘n’ roll, everyone knows there is only one genuine kind and that Mick Jagger remains its unrivaled incarnation,” and, “Without Mick, the Stones would have been over by 1968.” These assertions appear not just disputable, but unnecessary – does Jagger really need Mr. Norman’s endorsement?

Norman then invites the reader to fantasize:

Jagger’s reputation as a modern Casanova is unequaled. . . looking at the craggy countenance, one tries but fails to imagine the vast carnal banquet on which he has gorged, yet still not sated himself. . . the unending gallery of beautiful faces and bright, willing eyes. . . the countless brusque adjournments to beds. . . the ever-changing voices, scents. . . the names instantly forgotten, if ever known. . .

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-