Lapvona Is a Morality Tale With an Empty Heart

Recent studies of medieval literature, language, and history have argued for a more connected understanding of preindustrial, pre-capitalist societies and post-industrial ones. While there has often been an emphasis on modern capitalism’s differences from medieval (European) feudalism, the two have plenty of similarities—the exertion of human power on natural landscapes, responses to natural disasters and economic fallout, and the use of labor in convoluted and exploitative ways. Despite obvious and important differences, medieval relationships to capital, or labor, or nature often overlap with our own in significant ways, including in an understanding of humankind as entwined with nature, but ultimately powerless to control it. In his Environmental History of Medieval Europe, Richard Hoffman demonstrates this with an anonymous medieval lyric:

A man may a while Nature beguile by doctrine and lore;

And yet at the end will Nature home wend, there she was before.

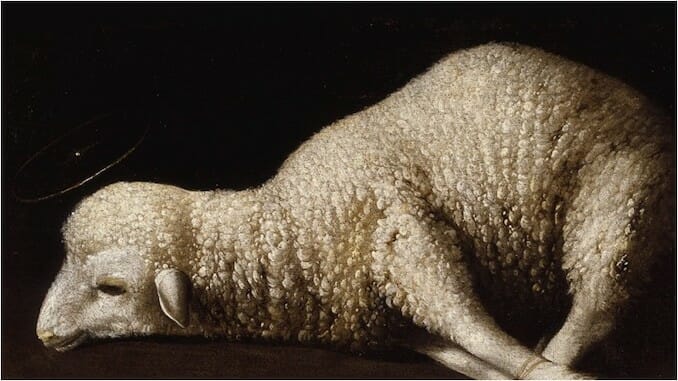

Lapvona, Otessa Moshfegh’s newest novel about a medieval town haunted by deceit, seems to be a product of a similar shift. It aims to present a feudal society grappling with its own relationship to extractive practices and subjugation of nature. Its larger goal is to make these practices resonate with late capitalist instances of the same: the ways the Global North’s relationship to nature has grown from twisted roots deep in European history.

Lapvona itself, the town the novel is set in, is a vibrant but unsettling place. Only a little of the book covers its existence before the drought begins hanging over the landscape: “It was all gray. The trees were bare. The roads were nearly white with arid dirt.”After this transition, strange things begin to happen in Lapvona: thirst-induced visions, cannibalism, flower beds springing from the cracked dry earth. As a character, Lapvona is more interesting than many of its inhabitants: it is a piece of traded land “wanted for its dirt”, it is an unstable home to hundreds of people, and it is the site of several natural disasters unfolding over the four seasons the book is divided into.

Moshfegh’s previous work is so good because it works from deep familiarity with its subject matter and. most particularly, its setting. New York in My Year of Rest and Relaxation, Moshfegh’s magnum opus about a woman sleeping through her life, is not just accurate but sparkling; the several-block radius its narrator lives in comes alive through bodega trips and laundry runs done with sleep-crusted eyes and Xanax-induced dissociation. The town of Lapvona, though beautiful and terrible, is more of a dream than a place. It’s a container for the various supernatural events that occur; tracing its geography beyond the basics is impossible and beside the point.

One of the novel’s main plots follows shepherd’s son Marek’s move from Lapvona itself to the manor that sits above it. After his involvement in a gruesome crime, he is selected by the lord of the village to come and live with him as his son, and to take part in the rituals of gluttony and self-debasement that life in the manor carries with it. In the same way, Lapvona’s harshness comes through, so does the manor’s depraved excess, which Marek adjusts quickly to: “He couldn’t bear to revisit the old world of nature. He felt too ashamed, and too guilty, and too superior all at once.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-