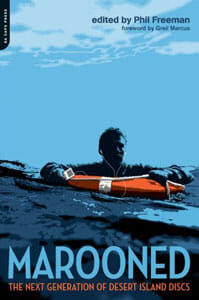

Phil Freeman (ED.)

The Sand and the Fury

Music critics sound off on every audiophile’s favorite hypothetical

There’s a lively debate going on in music circles today, and it’s not about which album you’d choose to spend the rest of your life with if washed up on a deserted (meaning: tourist-free, condo-free, shirtless-Matthew-McConaughey-jogging-down-the-beach-free) tropical island. The pressing question is: Would your chances of surviving on such an island—foraging in the brush for cockroaches and spiders to eat, sparking a fire using twigs and dry grass, slurping coconut milk—be any better than the album’s chance of surviving the hyper-convenience of our digital-delivery age?

Any artists who are remotely tech-savvy can record a song and upload it to their website minutes later for their fans to purchase or download free of charge. The idea of 18-wheelers and distributors and retail chains and rude cashiers and mountains of jewel cases in landfills seems vaguely absurd. Artists are no longer beholden to label release schedules. Music fans are no longer beholden to Ye Almighty Plastic Disc, especially un-rippable, copy-protected ones label execs might as well just post on Half.com and sell for $3.99 themselves.

Which brings us to Marooned, a collection of music critics building a case for why the album format is worth a damn. And they do this by discussing the albums that punctured their emotional dam. The testimonials contained in this book show that us human beings caught in the inertia of the mundane occasionally stumble upon a piece of art that flips a light switch in our brain, illuminating something profound and meaningful and even—are we allowed to print the word?—beautiful.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-