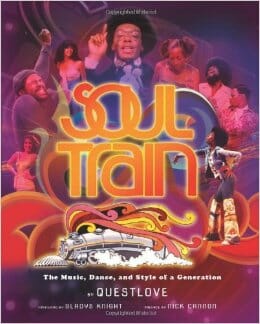

Soul Train: The Music, Dance, and Style of a Generation by Questlove

The Hippest Trip

What could be better suited to a large, shiny, coffee-table book than Soul Train?

Everything about the old TV show feels tailor-made for the coffee-table format: gleaming grooves, stunning dance moves, amazing outfits, beautiful—or, at the very least, sweaty—stars.

So now we have such a book, with prose handled by The Roots’ drummer Questlove, a well-known soul aficionado…and Soul Train devotee. For parents out there: Questlove says Soul Train was the only show his parents allowed him to watch as a child “except Sesame Street.” Look how well he’s doing for himself.

The only thing this book lacks? A pair of speakers—or better yet, speakers connected to a video screen. Presumably, that deficiency will be remedied when the Soul Train Deluxe edition comes out some decades from now.

Don Cornelius, visionary host, originally worked as a back-up radio DJ and news-reader in Chicago. On the side, he put together concerts that brought local musical groups into one high school, then on to another school, then to a next, in a series. It “felt like a train” said Cornelius, and just like all trains, it cost too much.

Cornelius adapted, creating a TV show instead, with dancing teenagers. What started “small,” “no frills,” and “black and white,” soon developed into a five-day-a-week live show syndicated in eight large cities. “Fourteen months after the first local airing,” Soul Train aired nationally Oct. 2, 1971, and eventually moved from Chicago to star central: Los Angeles.

Casual dabblers in Soul Train likely know it best from the show’s first decade, when it brought on most of the big names in soul and funk—Al Green, Aretha Franklin, Gladys Knight, James Brown, the Jackson 5—and explicitly endorsed products for African Americans during advertisement segments. Soul Train represented “[t]he first time that many people had ever seen Black Americans at the center of an entertainment television show,” writes Questlove. It also provided “some of the first opportunities to buy television advertising and create ads targeting the African American audience.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-