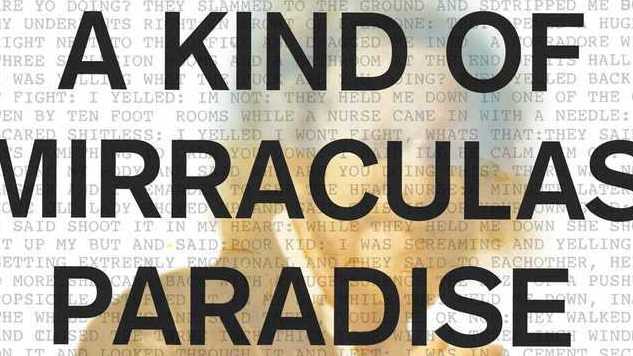

Paranoia Is Like Background Radiation, and A Kind of Mirraculus Paradise Gets It Right

WHAT DID THE SCHITZOID SAY AT THE FOOTBALL GAME WHEN

HE SAW THE TEAM HUDDLING ON THE FIELD?

THJEIR [sic] MAKING PLANS TO GET ME

That joke comes to us via Sandra Allen’s righteous, empathetic debut, A Kind of Mirraculas Paradise. Part memoir, part translation, part treatise and part contextual study, Paradise finds Allen interpreting her Uncle Bob’s writings after he mails her his autobiography. Bob, a self-professed “psychotic paranoid schizophrenic” who was dubbed as much after being “unable to identify with reality,” wrote pages containing both damaging accusations against Allen’s family and views on race and women many may find detestable. Allen uses the manuscript as a jumping off point to streamline Bob’s life story in Paradise, peppering it with indispensable bits of her uncle’s original language—denoted by the capital letters—throughout.

Despite the disease’s popular conception, Bob’s paranoia in Paradise is not a dramatic aspect of the narrative. In this way, it mirrors my own experience with the sensation, something more akin to an Instagram filter or background radiation, devious and powerful and hidden in its omnipresence. The major inconsistencies Allen has to reconcile—about how Bob was treated by his father and the mental health medical system (if it could be called that during the ‘60s and ‘70s when Bob was within its coils), including moments of cruelty and torture Bob recalled that others could not—could be attributed to the persecutory mindset paranoia can catalyze.

It is an odd thing, paranoia. It’s easily lampooned and culturally accessible, but it’s seldom experienced or portrayed so elegantly as Allen does here. Bret Easton Ellis’ novels, Robert Browning’s dramatic monologues, Gillian Flynn’s razor-sharp thrillers, all of these revel in the more horrible and fantastic forms of paranoia for art.

It is an odd thing, paranoia. It’s easily lampooned and culturally accessible, but it’s seldom experienced or portrayed so elegantly as Allen does here. Bret Easton Ellis’ novels, Robert Browning’s dramatic monologues, Gillian Flynn’s razor-sharp thrillers, all of these revel in the more horrible and fantastic forms of paranoia for art.

My own experiences are less dramatic. At a high, the paranoia takes the shape of an institution or cabal, a group of people which are, in the least, concrete and can be called by name. I remember in college, for example, a fellow track athlete named Donnie. Donnie lived with me in the same dorm and became a close friend in a campus wherein I often felt alien and targeted. We would play pool almost every night in the common area, becoming something like competent, when all of the sudden Donnie was gone. I was convinced that the college had removed him, and not only that, but had removed him to get at me. An odd error on my grades was evidence of deceit, I screamed, and now that I had a friend they had cruelly removed him, taken him away from me, made me yet again alone. I knew, even as I said these things, that they were false.

I also knew, gun to my head, that I believed them.

At its worst, I could not even name a college or cabal or group attempting to harm me. I was a victim of Them…of Others.

Paranoia colors my life now in a far less dramatic—but infinitely more damaging—way, via episodes of social psychosis wherein there is no convincing me that friends, people I love, are not conspiring against me. Most often, they are plotting a way to exclude me, replace me, untenable feelings which I lash at with the desperation of the drowning. A simple hello is a prelude to a life spent with the interloper and without me; a failure of an introduction is a herald of my coming death.

Since they feel so devastatingly real to me, I attempt to convey my feelings, to reveal the architecture being built around me so that those who are perpetuating it may hasten its demolition, may absolve themselves of their terrible (hopeful) mistake. But these structures are not real, they merely feel real, and the disconnect is such that it’s borderline impossible for me to get them across, like describing invisible cathedrals. This can drive me to the verge of tears, as the frustration mounts; I have dreams, always dreams, wherein planes are about to plummet and no one can understand as I warn them.

So it’s significant that Allen’s subtle portrayal of paranoia in a book about schizophrenia does the disorder justice by not naming it. Tinfoil hats and webs of thread removed, A Kind of Mirraculas Paradise asks you to consider the disease by demonstrating it in the way I live it: always on the periphery, impossible to disentangle, necessary to navigate as best as one can.

B. David Zarley is a freelance journalist, essayis, and book/art critic based in Chicago. A former book critic for The Myrtle Beach Sun News, he is a contributing reporter to A Beautiful Perspective and has been seen in The Atlantic, Hazlitt, Jezebel, Chicago, Sports Illustrated, VICE Sports, Creators, Sports on Earth and New American Paintings, among numerous other publications. You can find him on Twitter or at his website.