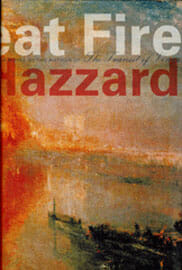

The Great Fire

Shirley Hazzard makes a grand return to the literary stage with The Great Fire, winner of the 2003 National Book Award. Its predecessor, The Transit of Venus, has become a modern classic, and this newest book—so exquisitely written—nearly convinces me that every novel should require 23 years of labor. This is a story of far reaches and big themes: desolation and love, despair and hope, war and peace. The unfolding plot, its slow pace and Hazzard’s precise, almost pained, word choice reflect a time far removed from our own: the late 1940s and the aftermath of an inevitable war after the war to end all wars. The story moves like a strange, sad picaresque, where all adventure has been exhausted, but the old heroes and heroines go through the motions of their now ordinary lives; they seem hushed, shell-shocked, loathe to make a sudden move: “Two years into peace and bored to death by it. Each must scratch around now for some kind of compromise and call it destiny.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-