Standing by Words – African Novels

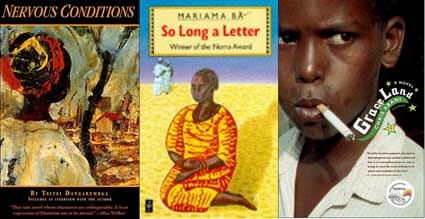

It’s nothing new to argue that Americans don’t pay enough attention to foreign fiction; one wonders if the situation were ever different. Nineteenth-century audiences crowded docks to receive the latest installments of Dickens’ The Old Curiosity Shop, but the author, whose outsized creations bump against the sky of one’s mind like Thanksgiving Day parade balloons, probably inspired a similar extravagance in readers. And when a foreign work does register on our radar, it’s typically from Europe, Japan, Central or South America. With rare exceptions—Achebe, Gordimer, Soyinka—even book junkies don’t hear much about African fiction. So here, drawn from reading lists, friends’ recommendations, Internet jags and bookstore browsings, are four compelling works of African fiction not titled Things Fall Apart.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-