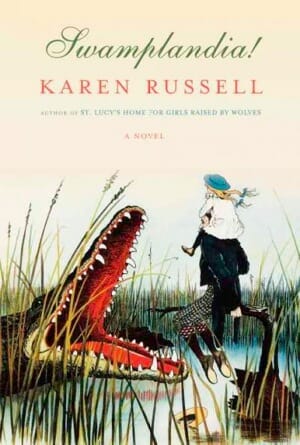

Swamplandia! by Karen Russell

New Days for the New World

It’s of note that the kind of unflinching look Swamplandia! takes at the devastation wrought on the Americas and their people from 1492 until the present has, until now, been largely the realm of immigrant writers and writers of color. In Swamplandia!, an Anglo-American girl from Florida churns out brilliant, brutal passages like this one, in which narrator Ava waxes historical: “Prejudice…was a kind of prehistoric arithmetic…It meant white names on white headstones in the big cemetery on Cypress point, and black and brown bodies buried in swamp water.”

Pinch me. It’s been rare to hear such words from a mouth like Russell’s. It suits her, and the rest of us, so beautifully. If this book does not represent one of the first instances in recent literary memory where work of the mainstream Anglo-American tradition reaches to align itself with the richly evocative, distinctly immigrant aesthetic that has characterized many of the most notable books of the last few decades, then it is certainly among the best of those attempts.

Like some lost, ancient tribe, the family around whose Russell’s story centers is their own cosmos, the rulers and only permanent residents of an island in the Everglades they’ve named Swamplandia!. This, their clan’s adopted homeland, exists as a kind of rustic tourist park, where sun-burned Midwesterners can come to watch matriarch Hilola Bigtree wrestle live alligators in an arena twice a day.

Russell creates warm, lively characters whose interactions with one another are spontaneous and organic. And slyly, her work begins to approach the most good-natured among the goals of the eccentric members of the Bigtrees. It attempts to stake a place at the perimeter of certain expectations of class and race. In the context of today’s literature, the book finds its orientation among much of the fiction birthed out of the Western immigrant experience.

Readers will recognize in Swamplandia! the brilliant comic strategies of Zadie Smith’s White Teeth, another first novel by a preternaturally talented young woman. We also see glimpses of the post-apocalyptic zaniness of Gary Shteyngart’s radiant latest novel, Super Sad True Love Story. In both its humor and its exploration of families writhing under the heavy grip of their own mythology and the myths of the land, it also suggests Junot Diaz’s Pulitzer-winning The Brief and Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao. All three works chronicle the immigrant experience. And like them all, Swamplandia! laughs, at times, to keep from crying. This book similarly reaches for core truths—even ugly ones—by pretending not to take itself seriously.

Also, any discussion of the dynamics shifted by emergent work like Swamplandia! is incomplete without mention of Dave Eggers. His genre-bending last two books, What is the What and Zeitoun, presented the respective accounts of a Sudanese Lost Boy and a Muslim family in Katrina-era New Orleans with groundbreaking cross-cultural creative effort. It is hard to imagine that Swamplandia! could have been created in a climate with waters untested by books like these—works by which mainstream advocates bring a marginalized experience to accepted literary notice.

If a road has been paved for Russell by these efforts, there is an important distinction to be made. Where Eggers pushed the envelope of convention by using novelistic techniques to tell the true stories of people whose cultural perspectives differed from his own, Russell uses a fictional narrative situated within her own culture to grapple with human dilemmas that have more commonly been explored using different cultural tools than she herself would seem to posses. Does Russell know the feeling of exile from a homeland? The rites of passage into the first world? Her book surely does.

In its exploration of life on the margins, Russell’s work has also drawn clear lines to the 20th century gothic Southern tradition. Women writers like Carson McCullers, Harper Lee, and Flannery O’Connor wrote from bastions of white privilege but viewed with horror the violence on which their comfort was predicated. The work of these writers, like Russell’s here, channeled the sense of alienation any highly sensitive soul coming of age in a brutal world inevitably comes to feel. They used this sensibility to tell the stories of characters marginalized by the world’s brutality: freaks, hunchbacks, children, and, in the Jim Crow South, even so-called Negroes. From the comfortable center, these women chose to write the edges.

We are reminded of Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird, and the continuing public challenge that book raised in its direct confrontation of race—an interaction with ideas very much at issue in the day, but previously most often the territory of writers of color. We are also reminded of McCullers’ The Heart is a Lonely Hunter, a book about characters at the outskirts of their culture. Like these predecessors, Russell has carefully insisted upon her own inheritance, confounding expectations for a writer of her race and background.

Swamplandian siblings Ava, Kiwi, and Osceola Bigtree live in an insular world at the story’s onset. Their world comes complete with its own founding myths. The children pay visits to the museum on the isle of Swamplandia!, to view artifacts of their own family’s history—their mother’s wedding dress stands on display, alongside taxidermied alligators wrestled by their grandfather. Their father and the head of their tribe is Chief Bigtree, recently widowed. Their paternal Grandfather Sawtooth founded Swamplandia! during the Great Depression. They live in many ways as cultural outlaws, unaligned with the mores of the land.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-