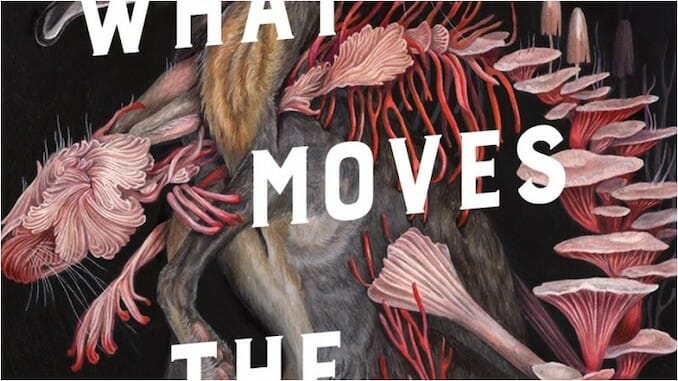

What Moves the Dead Is Delicate, Atmospheric, and Thoroughly Creepy

T. Kingfisher’s Nettle & Bone is one of the best fantasy releases of the year thus far, a bittersweet and fiercely feminist magical fairytale about found families and seemingly impossibility quests. And now, just three months later, it looks as though she’s released one of the year’s best horror stories as well. What Moves the Dead is, at its most basic, a retelling of the Edgar Allan Poe classic “The Fall of the House of Usher,” but one grounded in complex character dynamics and bitingly dark humor.

In a publishing landscape where doorstopper-sized tomes are rapidly becoming the rule rather than the exception, Kingfisher stands out as an author who truly lives the axiom less is more. A novella cocking in at less than two hundred pages, every word of What Moves the Dead feels carefully chosen and deliberately arranged for maximum emotional impact. The sharp descriptors that paint a vivid picture of the Usher mansion, the quietly escalating sense of dread that builds from page to page—-it’s all a master class of storytelling that brings the famed halls of the house use of Usher to vivid, terrifying life. Every item—whether living, inert, or somewhere in between—feels like a potential threat, leaning fully into the book’s atmosphere of mistrust and paranoia.

The story follows Alex Easton, a non-binary retired soldier from the fictional country of Gallacia, who is summoned to rural Ruravia to help a dying childhood friend, Madeline Usher, by her brother Roderick. Shocked at the emaciated, obviously ill state of both Usher siblings, as well as the dilapidated state of the crumbling Gothic manor they live in, Easton is unsure both of what to blame for their rapid decline and how best to help them recover.

Aided by a visiting American doctor and a local mycologist, Easton embarks on a quest to figure out just what’s wrong with his friend—and how the strangely glowing lake at the bottom of the property fits into everything. As ??an audience stand-in, Easton is an intriguing narrator, with a bitingly dry wit and a soldier’s refusal to believe in anything other than what they can see directly in front of them. Along the way, we’re treated to interesting explanations of their home country and how its society created the “sworn soldiers” who use their own set of specific pronouns (a fact which comes into play toward the novella’s conclusion), as well as repeated encounters with an increasing number of deeply creepy hares, who don’t exactly behave the way that animals in the real world are supposed to. (Apologies to everyone who loves rabbits, between this and Melissa Albert’s Our Crooked Hearts it’s been a rough summer for y’all.)

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-