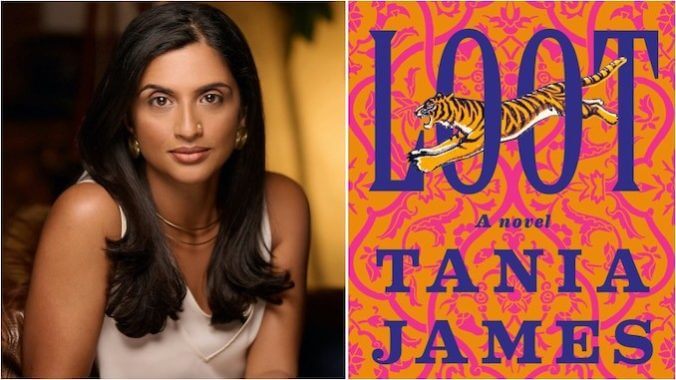

Tania James Breaks Down Loot, One of the Year’s Best Historical Novels

Photo: Elliott O’Donovan

Even if you’re not a person who tends to gravitate to historical fiction as a reader, you’ve probably heard of Tania James’s Loot. The novel, which hit shelves earlier this summer, landed with a ton of buzz behind it, and rightly so From its unique subject matter (the origins of an eighteenth-century automaton from the Kingdom of Mysore) to its timely reflections on art, history, and Western attitudes about who is capable of owning either of those things, this is a complex story about creation, ownership, colonialism, and memory, and it’s going to land on a ton of “Best Of” lists come the end of the year.

Loot follows the story of Abbas, a poor 17-year-old artist who’s recruited by Tipu Sultan, the ruler of Mysore, to apprentice with French clockmaker Lucien Du Leze. Their task: Create a giant wooden automaton of a tiger mauling a near-life-size British soldier. This giant toy—which once played music as the great cat snorted and attacked—is a real thing, and is currently housed in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. But how did it get there? And who were the men who made it?

Those are just some of the questions at the heart of this novel, which spans multiple decades and continents, features almost half a dozen main characters, and tells a story that walks a fine line between whimsy and tragedy. And the end result is something that is as beautiful and strange as the object at its center.

We got the chance to chat with James herself about her decision to try her hand at historical fiction, the real-life Tipu Sultan, and lots more.

![]()

Paste Magazine: Loot was your first historical fiction novel — how was writing in this genre, about fictionalized versions of real historical figures different (or more challenging or more fun) than your previous work?

Tania James: Let’s start with the fun! Writing historical fiction is the closest I’ve ever come to writing collaboratively, not with another person but with history itself.

Sometimes—well, a lot of times—I found the historical research to be a bit tedious, but then I’d stumble across a detail that would prompt my own imagination in a direction I hadn’t anticipated beforehand.

Paste: Tell us about where the idea for Loot came from and the themes you wanted to make sure the book explored.

James: The earliest and clearest inspiration for Loot was the automaton itself, Tipu’s Tiger, which is housed in London’s Victoria & Albert Museum. Tipu’s Tiger is a spectacular 18th century automaton composed of a six-foot-long wooden tiger that’s mauling the throat of a prone English soldier. Back in the day, you could turn the hand crank, and the tiger would grunt while the soldier groaned, all while organ music played from within. I’d never seen a work of art—mechanized or otherwise—that was so bold in its contempt of British power, so irreverent and anti-colonialist. So I knew I wanted to write about Tipu’s Tiger, but it took me a while to realize that the novel would focus more on the makers of the automaton than the automaton itself.

In terms of theme, part of my revision process is keeping close track of certain words and phrases that keep echoing and mutating throughout the novel. Foremost was the title itself—loot—which is an English word with Sanskritic origins. So we’re not only talking about the movement of art, but also the movement of people, of power, of culture and language itself, and what is lost and gained along those migrations. Another recurring phrase was “leaving a mark,” which is one of Abbas’s early ambitions: to create a work of art that will outlast him. But to what extent can one control their own artistic destiny, let alone the trajectory of one’s work? And what defines an artist, great or otherwise?

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-