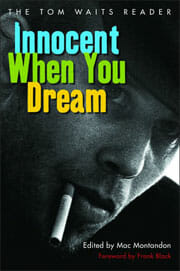

The Tom Waits Reader

Straight-Talking Liar: Beat raconteur, avant garde floor show, highway spirit, patron saint of the down ‘n’ out

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-