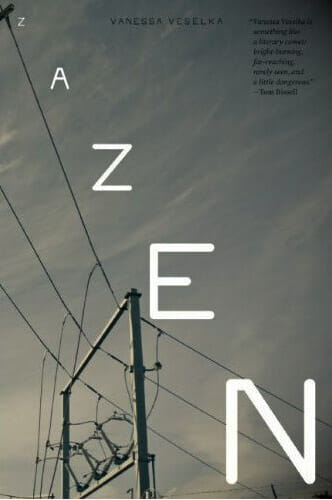

Zazen by Vanessa Veselka

Rebels Who Refuse to Rebel

In dystopian novels, we often find ourselves cheering on a protagonist’s desperate escape. We want our hero to not only question the beliefs that have so deeply brainwashed his or her society, but to actively pursue some plan of subversion that becomes the catalyst for an all-out rebellion against a totalitarian regime. From enduring classics such as A Brave New World to the current flavor-of-the-week in the young adult genre (The Hunger Games, anyone?), this trope has proven its staying power. We not only want rebellion, but expect it.

The urge to subvert feels even more relevant and cathartic today, during times of economic turmoil and transformative cognition driven by newer technologies and forms of communication. We yearn to have overwhelming systems of oppression dismantled by an outsider who knows the inside. Though we may anticipate the rebellions and find deep satisfaction in them, we also see dystopian novels today that offer a rare form of resolution, through rebellions that aren’t committed.

Zazen by Vanessa Veselka not only grants us access to this unexpected point of view, but also creates a world where uprisings and escape seem futile, despite fashionable interest in them.

Zazen’s narrator, Della Mylinek, is a paleontologist-cum-waitress who finds herself surrounded by all sorts of rebels and outsiders: hippie parents, leftist radicals who start protests at Wal-Mart, punks with dyed hair, vegan coworkers who host sex parties. For her, counterculture has always been the norm.

But Della has also grown up to find herself stuck in a politically tumultuous America (specifically, the Pacific Northwest), where bombs go off and no one really understands if war is happening or not. From the very start, Della’s particularly unreliable narration absorbs us, and we constantly question what she is thinking and whether it has any basis in reality. A host of psychological issues makes it even more difficult for her to sort things out. She deals with persistent feelings of futility, possible post-traumatic stress disorder from a sister’s grisly death and bouts of intense anxiety that even motivate her to call in bomb threats of her own.

It’s only natural for readers to wonder whether the images of this crumbling dystopia, confusing the real and the figurative, simply stand as metaphors that Della has self-constructed to convey her own mental states. Are the places she refers to actual physical locations or just the war-torn landscapes in her mind? There is Old Honduras, and there is New Honduras—both seem real, yet not real at all.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-