The ABCs of Netflix: What to Watch from A to Z

As the pandemic stretches on (and on and on…), “Netflix and chill” has long since morphed to “Netflix … still.” While we have plenty of guides on the latest offerings from the hydra-headed streaming offerings out there, at this stage of the relationship, seems like a good time to change things up a bit. Since one strength of Netflix is its medium- and genre-spanning range of offerings, the following list provides 26 destinations (thank you, alphabet!) and includes a healthy mix of television and movies, of animation and live-action, of drama, documentaries and comedy specials. Pick a letter and go!

Avatar: The Last Airbender

Don’t be put off by M. Night Shayamalan’s clunky 2010 live-action adaptation. This richly animated TV series merges the wild imagination of Hayao Miyazaki, the world-building of the most epic anime stories, and the humor of some of the more offbeat Cartoon Network originals. Following the exploits of the Avatar, the boy savior Aang who can control all four of the elements—fire, water, earth and wind—the series is filled with political intrigue, personal growth, and unending challenges. Spirits and strange hybrid animals present dangers, but so do the people who seek power for themselves. This is one you’ll enjoy watching with your kids or on your own. —Josh Jackson

The Breadwinner (2017)

Having worked on both The Secret of Kells and Song of the Sea, Nora Twomey has taken a different tack than her Cartoon Saloon cohort, Tomm Moore, departing the mythology-rich shores of Ireland for the mountains of Afghanistan, focusing on the region’s own folklore against the backdrop of Taliban rule. The film is based on Deborah Ellis’s 2000 novel of the same name, the story of a young girl named Parvana who disguises herself as a boy to provide for her family after her father is seized by the Taliban. Being a woman in public is bad for your health in Kabul. So is educating women. Parvana (Saara Chaudry) understands the dire circumstances her father’s arrest forces upon her family, and recognizes the danger of hiding in plain sight to feed them. Need outweighs risk. So she adopts a pseudonym on advice from her friend, Shauzia (Soma Bhatia), who is in the very same position as Parvana, and goes about the business of learning how to play-act as a dude in a world curated by dudes.

Meanwhile, Parvana’s embrace of familial duty is narrated concurrently with a story she tells to her infant brother, about a young boy who vows to reclaim his village’s stolen crop seeds from the Elephant King and his demonic minions in the Hindu Kush mountain range. If there’s a link that ties The Breadwinner to Moore’s films, besides appreciation for fables, it’s artistry: Like The Secret of Kells and Song of the Sea, The Breadwinner is absolutely gorgeous, a cel-shaded stunner that blends animation’s most traditional form with interspersed cut out animation. The result mixes the fluid intangibility of the former with the tactile quality of the latter, layering the film’s visual scheme with color and texture. Twomey gives The Breadwinner ballast, binding it to the real-world history that serves as its basis, and elevates it to realms of imagination at the same time. It’s a collision of truth and fantasy. —Andy Crump

Clueless (1995)

The Beverly Hills reboot of Jane Austen’s classic Emma was a sleeper smash in 1995 and, much more importantly, gave the phrase “As if!” to pop culture. Alicia Silverstone is Cher, a pretty, vain, superficial LA teen who goes on a mission to turn ugly-duckling classmate Tai (Brittany Murphy) into a Superswan, only to find herself eclipsed and adrift. A soft-edged satire of nouveau-riche Angeleno culture and simultaneously of the teen rom-com genre, Clueless is neither the most subtle nor the most hard-hitting film of its era, but it’s surprisingly seductive, in large part thanks to Amy Heckerling’s scrupulously researched script, which captured a dialogue style that both represented and influenced teen-speak of the time. —Amy Glynn

Dolemite Is My Name (2019)

“I want the world to know I exist,” Rudy Ray Moore (Eddie Murphy) declares in Dolemite Is My Name. Awareness on a grand scale is an ambitious goal—but it didn’t stop Moore from trying. Rudy Ray Moore is a multi-hyphenate performer looking to propel his comedy career. After seeing Rico (Ron Cephas Jones), the local homeless man that visits where Rudy works, do stand-up, Moore decides to steal and refine Rico’s material. He assumes the character of Dolemite, a sharp, vulgar pimp who oozes confidence, and the “new” material kills in local clubs. Eventually, Moore signs a comedy record deal and charts on Billboard. Emboldened, he sets a new goal: to make a Dolemite film, exhausting all his personal expenses to do so. At the heart of Dolemite Is My Name is the smooth-talking man himself, played by Eddie Murphy.

The actor has, since 2012, been quiet in the public eye, taking years-long breaks between films. In 2016, he resurfaced for the drama Mr. Church, his performance praised but the film critically panned. Being hailed as his “comeback” role, Dolemite finds Murphy in fit comedy shape, tackling this lead part with gusto. He embraces Moore’s slightly goofy enthusiasm and can-do attitude without a hint of mocking. For a character like Dolemite, so deeply rooted in the Blaxploitation era of the ’70s and frankly riddled with so many stereotypical elements, Murphy succeeds by being earnest, even when delivering Dolemite’s raunchiest lines. He reminds us he’s one of the best at balancing drama and comedy. A figure who could have been an offensive caricature in the wrong hands, Dolemite, in Craig Brewer’s film, is so much more; we go beyond the surface of the character, exploring one man’s quest for stardom and the entrepreneurial risks he took to be the talk of the town. We get a film befitting of Moore’s legacy while simultaneously reminding audiences the star power of Eddie Murphy. —Joi Childs / Full Review

Eric Andre: Legalize Everything (2020)

The same wild ethos of The Eric Andre Show informs Andre’s first-ever stand-up special, Legalize Everything, which includes an awfully timely opening segment with Andre as an unruly New Orleans cop and anecdotes about the various drugs he’s taken. Legalize Everything anticipates what 2020 has become: a time to question authority and the racist systems we’ve been conditioned to accept, and also to be on a lot of drugs.—Clare Martin

Flowers

The dark, bizarre, hilarious, and deeply emotional series Flowers is nothing like what you might expect. Styled initially as dark British comedy (which begins with a thwarted suicide that’s played with sighing resignation), Sharpe’s alternatively dreamy and nightmarish series follows the exploits of a family whose members are all on the brink of a breakdown (and more often than not cross over). Flowers is about the kind of darkness that follows you like a shadow, and the various ways it can manifest. It sounds like a slog, but it isn’t in even the slightest. With its stunning cast, Flowers is an extraordinary work, deeply touching and mysterious, working like a fever dream to explain what goes on in our minds and how we manage to carry on. It can be challenging—the Japanese-English Sharpe plays what feels like a racial caricature—and yet, it’s all part of his strange take on otherness and finding one’s place in a world that seems built for other people. —Allison Keene

The Good Place

Some of the best sitcoms in history are about bad people. M.A.S.H., Seinfeld, Arrested Development: It’d be hard to argue that the majority of their characters aren’t self-involved, intolerant or downright assholes. It’s far, far too early to enter The Good Place into any such pantheon, but it’s relevant in pinning down why the latest comedy from Michael Schur (The Office, Parks & Recreation, Brooklyn Nine-Nine) feels simultaneously so cozy and so adventurous. Fitting into a middle ground of sensibilities between occupational comedies like NewsRadio and the sly navel-gazing of Dead Like Me, The Good Place is the rare show that’s completely upfront about its main character’s flaws, creating a moral playground that tests Eleanor’s worst impulses at every turn. Played by Kristen Bell at her most unbridled, she’s a vain, impish character—the type of person who’ll swipe someone’s coffee without a second thought, then wonder why the universe is plotting against her. She’s a perfect straight woman in an afterlife surrounded by only the purest of heart, but the show doesn’t hold it against her. If anything, following in the grand tradition of sitcoms, the show knows that we’re all bad people at one time or another. —Michael Snydel

Hannah Gadsby: Nanette (2018)

Nanette grows past the confines of a comedy special and into something completely different—a riveting screed against misogyny in all forms that utterly abandons its reliance on jokes. It is, despite being extremely funny, the anti-comedy special. That’s not a label I’m putting on it—Gadsby announces her intentions for the special very clearly. It’s a work of art that—as someone who both loves comedy and often feels conflicted about its place in our cultural landscape—I’ve been waiting for for a long time without even realizing it.

It is an extremely angry hour, an extremely cathartic one and an extremely necessary one. An art form cannot thrive if it refuses to look itself in the face and question its own necessity. If it does, it might emerge on the other side stronger and more vital. —Graham Techler

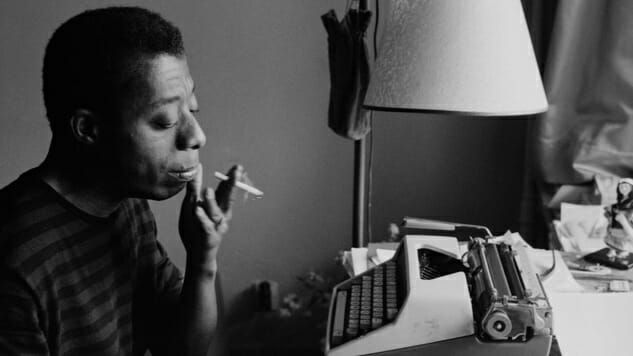

I Am Not Your Negro (2016)

Raoul Peck focuses on James Baldwin’s unfinished book Remember This House, a work that would have memorialized three of his friends, Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X and Medgar Evers. All three black men were assassinated within five years of each other, and we learn in the film that Baldwin was not just concerned about these losses as terrible blows to the Civil Rights movement, but deeply cared for the wives and children of the men who were murdered. Baldwin’s overwhelming pain is as much the subject of the film as his intellect.

And so I Am Not Your Negro is not just a portrait of an artist, but a portrait of mourning—what it looks, sounds and feels like to lose friends, and to do so with the whole world watching (and with so much of America refusing to understand how it happened, and why it will keep happening). Peck could have done little else besides give us this feeling, placing us squarely in the presence of Baldwin, and I Am Not Your Negro would have likely still been a success. His decision to steer away from the usual documentary format, where respected minds comment on a subject, creates a sense of intimacy difficult to inspire in films like this. The pleasure of sitting with Baldwin’s words, and his words alone, is exquisite. There’s no interpreter, no one to explain Baldwin but Baldwin—and this is how it should be. —Shannon M. Houston

John Mulaney: Kid Gorgeous at Radio City (2018)

John Mulaney: Kid Gorgeous at Radio City is of a piece with his last two specials. As before he doesn’t tell jokes, per se; he weaves long, elaborate stories out of his daily life, both now and as a child, focusing on how absurd the mundane can be. That might make him sound like some kind of Seinfeldian observational comic, but he avoids the clichés of that genre. It’s not the observation that makes Mulaney funny, or the recognition we might have for whatever he’s talking about. It’s the level of detail that he goes into, like when he talks about elementary school assemblies. He doesn’t just bring up that familiar setting and tell a few broad jokes about kids, teachers and school. He goes deep into one specific assembly he had to attend every year, describing in detail the Chicago police officer who specialized in child homicide and would give annual presentations on how to avoid or escape “stranger danger.” Mulaney creates a whole tableau out of this assembly, from the outlandish appearance of Officer J.J. Bittenbinder, to the cop’s increasingly ridiculous scenarios, with the comedy growing with every new detail. There’s no conventional setup or punchline, and little reliance on the universality of his topic; it’s just a story ostensibly pulled from Mulaney’s life and told in a fantastic fashion. —Garrett Martin

Kingdom

American (or even just Western) zombies are almost always the driving point of the narrative—representing big nasty threats like national anxiety about disease, nuclear war, capitalism, the collapse of society, and racism—often limiting the genre’s possibilities and focusing their plots largely on external forces. By contrast, in Kingdom (transported to South Korea’s Joseon period) these stories become more interested in how existing structures (and the normal people living inside them) handle the threat, and how coping makes them better equipped for the inevitable return to normal. Western zombie shows allow their audiences to appreciate how society adapts to these monstrous allegories, forming the factional city-states of The Walking Dead (Alexandria, Hilltop, Woodbury) or the religious zeal of Santa Clarita Diet’s Anne Garcia (Natalie Morales); Korean zombies rage in a society that ultimately stays the same. The latter’s evils are amplified and exposed by the zombies, but the infected undead also catalyze a satisfying hero’s journey in the midst of misguided magistrates, fear-based isolationism, and class warfare. —Jacob Oller

Legends of Tomorrow

“Joyful” is an underused and underrated term when it comes to TV dramas. Too many series conflate “prestige” with sorrow, violence, and horror when it can (and should) also mean happiness and splendor. Legends of Tomorrow, though, is a drama that truly understands the meaning of joy. The series—which follows a rag-tag bunch of misfits through space and time trying to “fix” historical anomalies caused by villains and supernatural beings—can be flippant and glib, but it can also be devastatingly emotional. The bottom line is that it’s just good. For those who were turned off by its first episodes or even first season, dive in to Season Two (or even Season Three, if you’re really strapped for time) and go from there. It gets much, much better. Legends is the rare series that learns from its mistakes, always ready to grow and innovate to bring us the most bonkers but wonderful television. And unlike most other series (especially those dealing with superheroes), it isn’t afraid to change out its cast members when things aren’t working, which keeps each season feeling fresh while the stakes remain high.

Legends of Tomorrow is funny, strange, bizarre, beautiful, and silly. It incorporates puppets and unicorns and sentient lopped-off nipples, but also explores the the devastation of losing loved ones, of advocating for those who need a voice, and an ever-developing journey of self-discovery. Join us for the ride.—Allison Keene

Mean Streets (1973)

Martin Scorsese’s fourth film begins in voiceover—rising wise guy Charlie (Harvey Keitel) speaks as much to himself as to God, knowing he’s a hypocrite for asking for guidance while working for his crime boss uncle (Cesare Danova)—and ends in a conflagration of voices, the indifferent thrum of New York City blotting out the film’s inevitable tragedy. Despite everything everyone tells him, especially his elders, a chorus of first-generation Italian immigrants, Charlie vouches for his dipshit best friend Johnny Boy (Robert De Niro) and carries on an affair with Johnny’s cousin Theresa (Amy Robinson), whose struggles with epilepsy Charlie’s uncle relegates to a brain sickness unbecoming of anyone with whom Charlie would ever want to be involved. In between small-time grifts and messy bar fights and thankless errands for heavy-breathing mafia types—in between celebrations for returning Vietnam vets whose personalities are most likely blasted by PTSD, childhood neighborhood friends unequipped to understand anything about that experience on the other side of the world—Charlie spends all effort hiding the life he wants from the life he’s earning, from the life of his culture, his people, his neighborhood.

Scorsese, the obvious cinephile, drew much from the French New Wave, especially in this portrait of careless youth beset by an impossible existential weight, but every moment of Mean Streets breathes with the claustrophobic, non-stop energy of New York in the ’70s: dirty, atomized and stubbornly stuck in its ways. Johnny Boy will let Charlie down, Theresa will never settle for being a hidden fling, Charlie’s uncle will never let him, unless he can prove himself to be clean of the sins of his friends, take over that Italian restaurant from the scumbum who owes them too much money—meanwhile, Charlie’s friend Michael (Richard Romanus) has no patience left waiting for the money Johnny owes him, the money Charlie helped Johnny acquire. As Charlie knows too well care of his Catholic upbringing, the sins of the past always catch up to collect. With Mean Streets, Scorsese crafted an indomitable ode to his home, an apologia for the hypocrites on his street that could never outrun their fate, the urban monoliths of their immigrant experience always closing in. —Dom Sinacola

The Night Comes for Us (2018)

While Gareth Evans confounded fans of The Raid movies by giving them a British folk horror film (but a darn good one) this year, Timo Tjahjanto’s The Night Comes for Us scratches that Indonesian ultra-violent action itch. Furiously. Then stabs a shard of cow femur through it. Come for the violence, The Night Comes for Us bids you—and, also, stay for the violence. Finally, leave because of the violence. If that sounds grueling, don’t worry, it is. You could say it’s part of the point, but that might be projecting good intentions on a film that seems to care little for what’s paving the highway to hell. It’s got pedal to metal and headed right down the gullet of the abyss. It’s also got the best choreographed and constructed combat sequences of the year, and plenty of them, and they actually get better as the film goes along. There’s a scene where Joe Taslim’s anti-hero protagonist takes on a team inside a van, the film using the confines to compress the bone-crushing, like an action compactor.

Other scenes are expansive in their controlled chaos and cartoonish blood-letting, like Streets of Rage levels, come to all-too-vivid life: the butcher shop level, the car garage level and a really cool later level where you play as a dope alternate character and take on a deadly sub-boss duo who have specialized weapons and styles and—no, seriously, this movie is a videogame. You’ll forget you weren’t playing it, so intensely will you feel a part of its brutality and so tapped out you’ll feel once you beat the final boss, who happens to be The Raid-star Iko Uwais with a box-cutter. It’s exceptionally painful and it goes on forever. Despite a storyline that’s basically just an excuse for emotional involvement (Taslim’s character is trying to protect a cute little girl from the Triad and has a lost-brotherhood bit with Uwais’s character) and, more than that, an easy way to set up action scenes on top of action scenes, there’s something about the conclusion of The Night Comes For Us that still strikes some sort of nerve of pathos, despite being mostly unearned in any traditional dramatic sense. Take it as a testament to the raw power of the visceral: A certain breed of cinematic action—as if by laws of physics—demands a reaction. —Chad Betz

Outlander

Based on Diana Gabaldon’s immensely popular book series, Outlander follows the story of Claire Randall, a nurse in 1940s England who, while on a holiday to Scotland, gets transported back through mystical stones to the 1740s. There, as she fights for survival and a way home, she meets a tall, dark and handsome Highlander name James Fraser, and the rest is history. Except that Outlander actually does a really wonderful job of tracking the couple’s place throughout history, providing tense, riveting and yes romantic storytelling along the way. The series’ truly wonderful cast is augmented to the stratosphere by its leads, whose chemistry will make you believe in love at first sight. Full of battles, political intrigue and gorgeous on every level, the show is a wonderfully cozy (and sexy) adventure. From its hauntingly beautiful theme song by Bear McCreary onwards, Outlander will transport you to its dangerous, surprising world as quickly as those magical stones. —Allison Keene

Parks and Recreation

Parks and Recreation started its run as a fairly typical mirror of The Office, but in its third season, the student became the master. As it’s fleshed out with oddballs and unusual city quirks, Pawnee has become the greatest television town since Springfield. The show flourished this year with some of the most unique and interesting characters in comedy today. With one of the greatest writing staffs of any show, Parks and Recreation is only got better with time. —Ross Bonaime

Queen Sono (2020)

For some, Netfilx’s first original African series may be worth checking out just on the merits of it being an original African series. For others, the premise—Pearl Thuso’s titular character works for a secret organization that works to counter criminal threats and activity—may be just the Alias-adjacent vibe they are looking for. With its approval for a second season after an initial six-episode arc, watching Queen Sono won’t take as much of an investment as the more traditional 23-episode run (remember those?), and odds are, like pretty much any show after its first 5-6 episodes, Kagiso Lediga’s show will continue to hit its stride in Season 2. —Michael Burgin

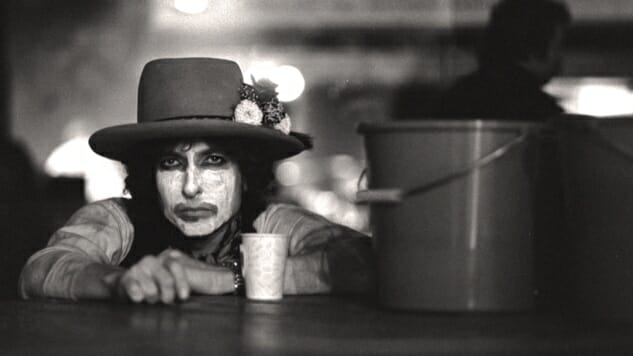

Rolling Thunder Revue: A Bob Dylan Story by Martin Scorsese (2019)

Bob Dylan’s life and career are so encased in myth that it can be hard to untangle the romanticism from the reality. As much a symbol as he is a man, Dylan has spent most of his adulthood resisting being labeled the voice of his generation while slyly welcoming fans’ desire to dissect his every utterance, devoting much of the last couple decades opening up the vaults to release a series of official “bootleg” recordings associated with his most iconic albums and tours. He invites us to look deeper and listen harder, as if the answers can be gleaned from closer study. Long before David Bowie, Tom Waits, Madonna or Lady Gaga dabbled in persona play, Robert Zimmerman made us ponder masks in popular music. He’s both there and not there, which can be frustrating and fascinating. Both sensations are on display in Rolling Thunder Revue, the oft-spectacular, sometimes shtick-y chronicle of Dylan’s 1975 Rolling Thunder tour.

As is typical when depicting anything in the Dylan universe, this concert film/documentary simultaneously oversells its subject’s genius and provides overwhelming evidence of what a brilliant artist he is. The documentary’s full title should also be a disclaimer: Rolling Thunder Revue: A Bob Dylan Story by Martin Scorsese. Early on, the movie features a contemporary interview from Dylan confessing that he doesn’t quite remember what prompted Rolling Thunder or what his ambitions were. “I don’t have a clue because it’s about nothing,” he says, another example of obscuration and seduction. The movie is a “story,” which means some parts might be invented or exaggerated, and because it’s “by Martin Scorsese,” the whole film is filtered through one artist’s perspective on another. Scorsese is after something grander than mere documentation—more layers of myth are applied while trying to present an honest account of a tour and a performer. At nearly two-and-a-half hours, Rolling Thunder Revue is overlong but also overpowering, inconclusive yet undeniably stirring. It left me exhausted, but I kinda want to see it again. —Tim Grierson

Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse (2018)

There are, rarely, films like Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse, where ingredients, execution and imagination all come together in a manner that’s engaging, surprising and, most of all, fun. Directors Bob Persichetti and Peter Ramsey, writer-director Rodney Rothman, and writer Phil Lord have made a film that lives up to all the adjectives one associates with Marvel’s iconic wallcrawler. Amazing. Spectacular. Superior. (Even “Friendly” and “Neighborhood” fit.) Along the way, Into the Spider-Verse shoulders the immense Spider-Man mythos like it’s a half-empty backpack on its way to providing Miles Morales with one of the most textured, loving origin stories in the superhero genre. Plenty of action films with much less complicated plots and fewer characters to juggle have failed, but this one spins order from the potential chaos using some comic-inspired narrative devices that seamlessly embed the needed exposition into the story. It also provides simultaneous master classes in genre filmmaking. Have you been wondering how best to intersperse humor into a storyline crowded with action and heavy emotional arcs? Start here. Do you need to bring together a diverse collection of characters, nimbly move them (together and separately) from setting to setting and band them together in a way that the audience doesn’t question? Take notes. Do you have an outlandish, fantastical concept that you need to communicate to the viewers (and characters) without bogging down the rest of the story? This is one way to do it. Would you like to make an instant contemporary animated classic? Look (and listen). —Michael Burgin / Full Review

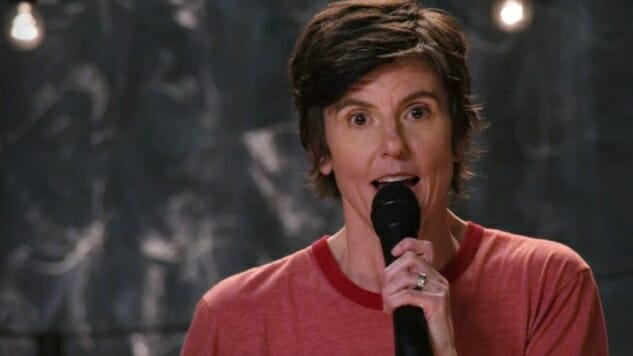

Tig Notaro: Happy to Be Here (2018)

Notaro, one of the true masters of deadpan, seems almost comfortable with her life on her latest special. Sure, she’s still self-effacing, to an extent, and still approaches her celebrity and success with a bemused distance, but she positively beams when she talks about her marriage and her two young twin sons. After all the grief that she mined for her career-making stand-up specials and sitcom, Notaro has more than earned the confidence and joy she shows in Happy to Be Here. Also fans of the Indigo Girls absolutely need to watch this special. —Garrett Martin

Uncut Gems (2019)

Uncut Gems begins far from Adam Sandler. In Ethiopia, an injured miner’s carried by a group of his fellow workers. We glimpse the miner’s nauseating leg break, though seeing it draws little sympathy from the mine’s non-native foremen, further infuriating the already collecting group of laborers, looking ready to riot. A fracas breaks out—chaos begets more chaos, as is the Safdie brothers’ way—while two workers slip away to head deep into the mine and chip out their own discovery. They seem to know where to find it: a huge gem, which they hold up for the audience. Cinematographer Darius Khondji’s camera moves closer to the gem to inspect, to create a tactile connection with the rock maybe, only to move in so close we plunge beneath its surface—caves within caves—and emerge, amidst a cosmos of particles, from Adam Sandler’s butthole. It’s 2012, the Celtics are in the Eastern Conference semifinals, and we meet Howard Ratner (Sandler) mid-colonoscopy. He’ll spend the majority of Uncut Gems waiting for the procedure’s findings, but any worries about what the doctor may find up his ass is quickly subsumed by the clusterfuck of Howard’s quotidian.

The proprietor of an exclusive shop in New York’s diamond district, Howard does well for himself and his family, though he can’t help but gamble compulsively, owing his brother-in-law Aron (Eric Bogosian, malevolently slimy) a substantial amount. Still, Howard has other risks to balance—his payroll includes Demany (Lakeith Stanfield), a finder of both clients and product, and Julia (Julia Fox, an unexpected beacon amidst the storm in her first feature role), a clerk with whom Howard’s carrying on an affair, “keeping” her comfortable in his New York apartment. Except his wife’s (Idina Menzel, pristinely jaded) obviously sick of his shit, and meanwhile he’s got a special delivery coming from Africa: a black opal, the stone we got to know intimately in the film’s first scene, which Howard estimates is worth millions.

Then Demany happens to bring Kevin Garnett (as himself, keyed so completely into the Safdie brothers’ tone) into the shop on the same day the opal arrives, inspiring a once-in-a-lifetime bet for Howard—the kind that’ll square him with Aron and then some—as well as a host of new crap to get straight. It’s all undoubtedly stressful—really relentlessly, achingly stressful—but the Safdies, on their sixth film, seem to thrive in anxiety, capturing the inertia of Howard’s life, and of the innumerable lives colliding with his, in all of its full-bodied beauty. Just before a game, Howard reveals to Garnett his grand plan for a big payday, explaining that Garnett gets it, right? That guys like them are keyed into something greater, working on a higher wavelength than most—that this is how they win. He may be onto something, or he may be pulling everything out of his ass—regardless, we’ve always known Sandler’s had it in him. This may be exactly what we had in mind. —Dom Sinacola / Full Review

V for Vendetta (2005)

Written by the Wachowski siblings and based on an Alan Moore comic, V for Vendetta has ambitions well beyond the typical action movie, not just to excite but to inspire. In an Orwellian future (that feels much less distant in 2020 than when it was released), a mysteriously vengeful masked man named V speaks about integrity and liberty. His ideas are vague, but his plans are specific, and they involve dynamite. Among rebellious movies that threaten to blow shit up in the end, V for Vendetta is closer to the confused philosophy of Fight Club than the visual poetry of Zabriskie Point. The details of V’s beef with society are hazy, but the film has a certain purity of spirit. V always wears his mask; removing it would cross a line that he—and the filmmakers—won’t cross, but opposite him is the expressive Natalie Portman. She’s critical as a reflection of V’s humanity, which may explain why the movie succeeds even with such muddled ideas. We accept him through her. —Robert Davis

Waco

I’m old enough to remember when the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms’ (ATF) raid of David Koresh’s compound resulted in a 51-day standoff that left 76 people dead. But I was also full of youthful naïveté and a strong belief about who was right and who was wrong. What I recall most from that time is thinking, “Why would anyone live in a cult and follow a man who thinks he’s God? Why would they give their life for him?”

Waco humanizes the story, making not only Koresh (Taylor Kitsch) but also his followers fully developed characters. The six-episode series focuses on the nine months leading up to the 1993 raid and its horrifying aftermath. By the time we meet Koresh, he’s already the leader of Branch Davidians, “married” to multiple women and the father of 13 children born by these various wives. He has a gift for recognizing the vulnerable and the wounded—the lost souls. In fact, what Waco does best is make Koresh not a monster. It almost poses the question, “Could he be a compassionate leader even though he was sexually abusing a young follower and perhaps others?” Which prompts another: Can I like the miniseries while also being concerned by its perspective? With the thought-provoking, risky, and engaging Waco, the answer is largely, “Yes.” —Amy Amatangelo

Extras

Creator Ricky Gervais and Stephen Merchant followed up the seminal sitcom The Office with the showbiz parody Extras. The setting’s different, but the cringe comedy and two season rule return in this devastating look at Hollywood’s smallest players, and how easily it is for one’s creative vision to be corrupted by the promise of fame. Gervais’s Andy Millman isn’t as pathetic as David Brent, but he’s still casually cruel and endlessly self-defeating, and although the verisimilitude of the universally familiar office setting is missing (replaced instead with a litany of very famous guest stars), Extras is an impressive companion to Gervais’s previous show. —Garrett Martin and Allison Keene

You

Every sophomore season of a TV show carries with it the weight of expectations based upon the first season, and You could very easily have fallen short of those expectations. However, the first new season made officially for Netflix (Season 1, let us never forget, originated on Lifetime) made a bold swing by relocating from the very specific pretensions of the New York literary world to the very specific pretensions of the Los Angeles wellness scene, and also in the process giving our dark lead Joe (Penn Badgley) a new, surprisingly hospitable new community to engage with—presuming, of course, he doesn’t find a reason to kill them all. The complicated way in which You plays with how we approach stories about men, women, and romance made this season as mesmerizing as the first, and the way in which the season finale teases a prospective Season 3 is finger-licking good.—Liz Shannon Miller

Zodiac (2007)

I hate to use the word “meandering,” because it sounds like an insult, but David Fincher’s 2007 thriller is meandering in the best possible way—it’s a detective story about a hunt for a serial killer that weaves its way into and out of seemingly hundreds of different milieus, ratcheting up the tension all the while. Jake Gyllenhaal is terrific as Robert Graysmith, an amateur sleuth and the film’s through line, while the story is content to release its clues and theories to him slowly, leaving the viewer, like Graysmith, in ambiguity for long stretches, yet still feeling like a fast-paced burner. It’s not Fincher’s most famous film, but it’s absolutely one of the most underrated thrillers since 2000. There are few scenes in modern cinema more taut than when investigators first question unheralded character actor John Carroll Lynch, portraying prime suspect Arthur Leigh Allen, as his facade slowly begins to erode—or so we think. The film is a testament to the sorrow and frustration of trying to solve an ephemeral mystery that often seems to be just out of your grasp. —Shane Ryan