Brecht Evens on Crafting Horror and Storybook Beauty in Panther

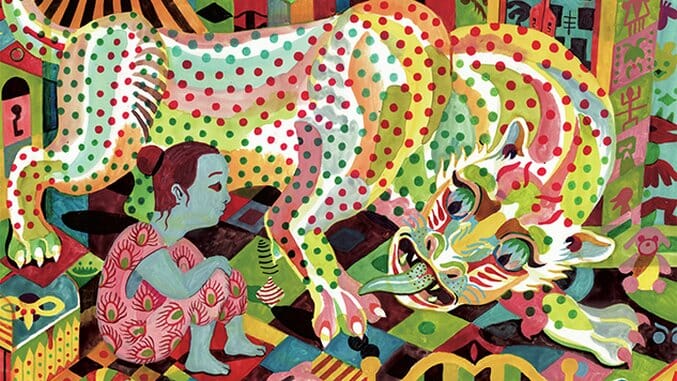

If you’re older than 30 and have creative aspirations, you may not want to hear that Belgian cartoonist Brecht Evens, who has produced three surpassingly lovely books and is at work on a fourth (due 2017), just reached that age this year. Go ahead and curse his name and his talent, but give thanks for it at the same time. His pages shine bright with color, almost floral in its abundance, and they rarely use panels. But they’re not just beautiful. The mind at work here thinks about less obvious ways of achieving truths. Nothing is straightforward. No omniscient narrator sets the reader at ease.

Panther, his latest, is the story of an imaginary friend who may not be all that friendly. That simple description, though, fails to convey the creeping dread that accompanies the reading experience, which stretches graphic art tension as far as it can go, driven by a child’s desperate need for love and attention. Evens is busy touring to celebrate Panther’s English-language release from publisher Drawn & Quarterly, but exchanged several emails with us to discuss his fine-art influences, development as an artist and longtime love of creating imaginary worlds.![]()

Paste: You can almost see a process of growing up over the course of your three books, in terms of their narrative subtlety and the ideas they address. How do you think you’ve changed since you began drawing/painting The Wrong Place?

Brecht Evens: I’m glad to hear you see progress, I suppose that is what every artist wants to hear. Basically I’m gathering more skills, while trying to hold on to old stuff that still works. I think my characters are getting more complex, too. I know my books are still instantly recognizable to someone who read The Wrong Place, and I think this is mainly because I haven’t dramatically changed my way of drawing the characters. The trick with a character having a signal color to his body and his speech still works for me. I’m not out to make dramatic changes just for the hell of it; it has to have a purpose. My next book (The City of Belgium) has a setup very similar to The Wrong Place: three characters running around in a city at night. So I’m playing with giving those books a shared universe, with “extras” from The Wrong Place showing up in the new book. Even the protagonists from The Making Of and Panther have a discreet cameo appearance.

Paste: I liked seeing you mention David Hockney as an influence. Could you talk a little more about that?

Evens: There’s something almost didactic about his work. It’s like he’s building a catalog of methods for other painters to use, saying, for example: “let’s try two hundred ways of drawing water” or “I notice you’ve been having trouble with rural landscapes, let me see if I can rustle up five hundred good ones.”

Paste: What other fine art influences do you have?

Evens: I feel like I shop around a lot. I’m going to list Elvis Studio (for the massive cityscapes), Ever Meulen (for the optical games), Georg Grosz (for the messy spaces), Giotto (for the decors), Charles Burchfield (for the watercolors alive with light, sound, vibration and movement), a touch of Bruegel, Persian miniatures and other medieval drawings, Picasso, Miro, Kuniyoshi, Saul Steinberg, outsider artists like Wölfli and Henry Darger, my former student Nina Van Denbempt and my fellow alumni Lotte Van de Walle and Brecht Vandenbroucke. There’s also a lot of artists I like that I can’t emulate yet, whose work has no useful elements I can chip off.

Panther Interior Art by Brecht Evens

Paste: I love seeing you mention Charles Burchfield. In my actual day job, I work at a museum, and we have one that goes out on display somewhat regularly: one of the crazy nature ones, not one of the sedate gray ones. Also: we do not have any of Hockney’s landscapes, but they’re just the best. He makes me care about landscapes in a way I never thought I could.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-