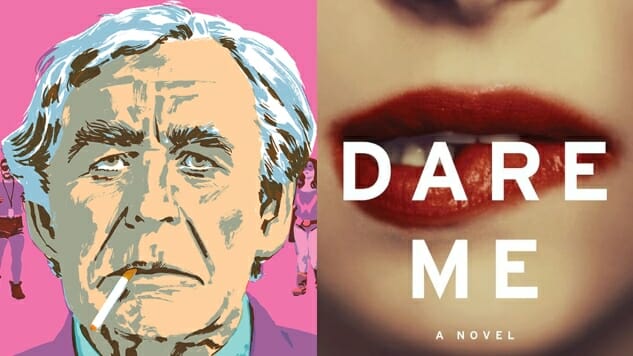

Hardboiled Superstars Ed Brubaker & Megan Abbott Discuss Comic Conventions, Criminals & Hollywood

Main Art by Sean Phillips/ Courtesy Reagan Arthur Books

Over the years, Paste Comics has had the privilege of playing fly-on-the-wall to a handful of truly impressive creator chats: Bitch Planet co-creator Kelly Sue DeConnick and The Handmaid’s Tale author Margaret Atwood; Hellboy mastermind Mike Mignola and international art legend Geof Darrow; Punisher scribes and punks-made-good Rick Remender and Matthew Rosenberg; and more. With just over 24 hours left on the clock for Paste Comics as its own section, we had to add just one more to the list: crime/noir superstars Ed Brubaker and Megan Abbott, who chatted over email and were kind enough to let us host the result.

Brubaker has a decades-long career in comics under his belt, pivoting from respected runs on titles like Catwoman and Captain America to his highly acclaimed original work, most of it with artist Sean Phillips at Image Comics. From Criminal to Incognito, Fatale, The Fade Out, Kill or Be Killed and back to Criminal, Brubaker and Phillips have established themselves as the names in crime comics. Brubaker has followed his noir sensibilities to Hollywood, contributing to HBO’s Westworld and teaming up with director Nicolas Winding Refn for Too Old to Die Young at Amazon.

While Abbott has contributed only a few times to the world of comics, her name is all but synonymous with modern hardboiled crime. Lending a much-needed female perspective to a genre infamous for flattening women to dames, broads or dead bodies, Abbott has won or been nominated for the Hammett Prize, the Shirley Jackson Prize, the Los Angeles Times Book Prize, the International Thriller Writers Award and multiple Edgar awards. Abbott also contributed to HBO’s acclaimed The Deuce, and is hard at work adapting two of her novels for film and television.

Paste readers can follow along with their chat below, and can find ample examples of both Brubaker’s and Abbott’s work at their local comic and book stores.

![]()

Bad Weekend Cover Art by Sean Phillips

Ed Brubaker: So, my new book takes place over a weekend Comic Convention—a sort of stand-in for the big Comic-Con down in San Diego every summer. I moved to San Diego as a kid, so I’ve been attending that convention on-and-off since I was like 8 years old.

But if I’m remembering right, isn’t your mother a crime writer, too? Did you guys go to Bouchercon or other shows like that growing up?

Megan Abbott: My mom’s a writer, but she didn’t really start focusing on crime stories until about the time my first novel came out in 2005. So we went to our first Bouchercon together. It was a big turning point in my life, actually. I’d never met so many people all in one place that loved the same dark, strange and wonderful stuff. The conversations I had that weekend—about Raymond Chandler and James M. Cain, about obscure B-noirs, about lost Cornell Woolrich novels, etc.—well, I still remember them. They opened my door to even more writers—Manchette, Goodis, Willeford…

But Bouchercon is a fraction of the size of Comic-Con, which is so dazzling in its scope and scale. What was it like as a kid?

Brubaker: Well, compared to what it is now, it was tiny. They held it at the El Cortez hotel in downtown San Diego, and there was a big dealers room, with booths filled with old comics and boxes and boxes of back issues from all over the country. I remember the first thing we did was my dad took me to a panel where Bob Kane was drawing Batman on a big overhead projector, and took questions from the audience. My mind was totally blown—I think I was eight.

-

-

-

-

- Curated Home Page Articles By Test Admin October 21, 2025 | 3:10pm

-

- Curated Home Page Articles By Test Admin October 21, 2025 | 2:57pm

- Urls By Test Admin October 21, 2025 | 2:57pm

- Curated Home Page Articles By Test Admin October 21, 2025 | 2:55pm

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-