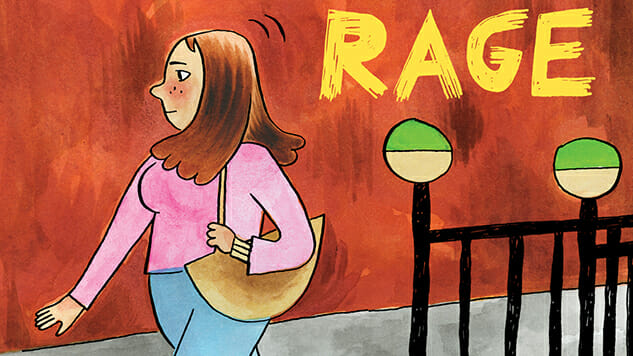

Vanessa Davis on the Raw, Romantic 20-Something Abandon of Spaniel Rage

Main Art by Vanessa Davis

Drawn in 2003 and published a decade ago, Vanessa Davis’ Spaniel Rage is the kind of slim book that has an impact out of proportion to its size, similar to Derek Kirk Kim’s Same Difference. Instead of innovating on sequential-art form or function, Davis’ casual diary comics draw from her time in New York and reveal a warm, familiar voice. She has a lot of free time. She goes out. She works at a crappy job. She sits around in her underwear. The collection showcases a storytelling ease between her writing and drawing; the confessional vulnerability doesn’t come off as self-serving or calculated (even the impression of nonchalance). Can that naturalism be taught? Probably not. Davis has done better and more complicated stuff in the years since (see her other autobiographic collection, Make Me a Woman), but Spaniel Rage holds an amazing freshness 12 years after it was published. It certainly deserves Drawn & Quarterly’s February reissue, complete with a new two-page introduction. Davis was pleasantly game to answer a couple of long emails full of questions, including some prying into her Publix sub order.

Spaniel Rage Cover Art by Vanessa Davis

![]()

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-