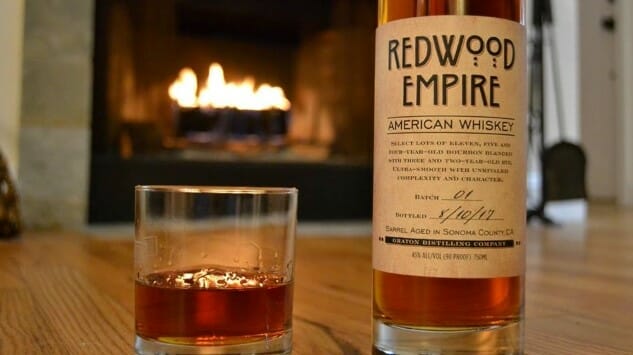

Redwood Empire American Whiskey

Photo via Graton Distilling Co.

I’ve written before, on a good number of occasions, about the burden of bringing a sourced whiskey to market for an independent distillery. I have to say that on a personal level, it chafes me to see young, independent distilleries shy away from the transparency of simply saying where their sourced whiskeys are being produced. So many treat it as anathema, and I genuinely don’t understand why. Do they really think that having some tiny font on a bottle that says “distilled in Indiana” is going to hurt sales? Would that not be preferable to raising the ire of the people who care the most about this sort of thing, which is the whiskey writers? It’s baffling.

Here’s another hypothetical: What if you distill and age part of the juice that goes into a blended whiskey, but source the rest? Does this absolve you of any responsibility to explicitly note that you still sourced the majority of the liquid in the bottle, because you produced a portion of it yourself? Am I crazy for thinking that a company shouldn’t go out of its way to hide that kind of information from the average consumer?

These questions are relevant to this review for Redwood Empire American Whiskey, a new product from Sonoma County, CA’s Graton Distilling Co. As suggested above, each bottle does contain some 2-year-old rye distilled and aged in California by Graton themselves. But each bottle also contains four other whiskeys that all hail from Indiana’s MGP, the U.S. superpower of sourced whiskey production, which include: 4, 5 and 11-year-old bourbon, and 3-year rye, a portion of which was aged in port and wine casks. And this is of course where transparency is missing. The word “Indiana” appears nowhere on the bottle, even in the fine print. It also appears nowhere on the website. The only way someone picking this up off the shelf in a liquor store might suspect it wasn’t entirely distilled in California was if they noticed it was labeled as being “bottled” by Graton, which suggests the possibility of being distilled elsewhere.

Let’s make something clear: This kind of aversion to transparency is patently unnecessary. The vast majority of drinkers don’t care one way or another, but they at least deserve accurate labeling. And for the drinkers who do care, they only want accurate labeling as what is essentially a courtesy—their actual assessment is going to be about what is in the bottle, as is mine. If the whiskey is good, it doesn’t really matter where it came from—unless you hide where it came from. Capisce?

Now, on to an actual whiskey review.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-