Catching up with Historian Paul Freedman of Ten Restaurants that Changed America

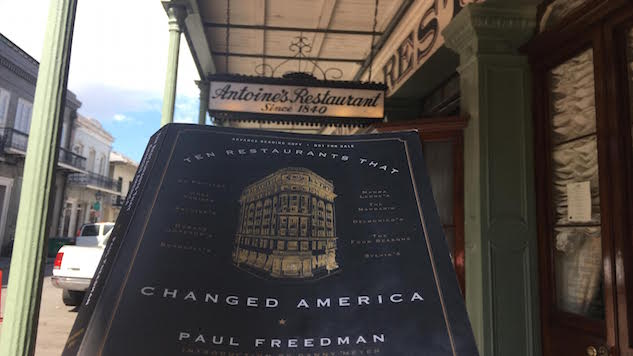

Food is a basic human need, yet nothing about it remains basic, as we learn in the new book, Ten Restaurants that Changed America, by Professor Paul Freedman of Yale University. Food is both a necessity and a commodity; at its lowest level it is sustenance, at its highest, an extravagance. Using food as a lens, Professor Freedman delves into the United States’ restaurant history of the last 200 years. Readers are invited on an elegant crawl: Mamma Leone’s and the Mandarin tell of food and immigration, Schrafft’s and Chez Panisse give insight into women’s rights, American homogeneity through Howard Johnson’s, and the regionalism of Antoine’s and Sylvia’s.

Like a master taster, Freedman is able to sniff out the subtleties in each restaurant that influenced culture, society, industry and politics in America. With each dish, Freedman explores how to best define the ingredient-mashed melting pot that is American cuisine. As if each chapter were not already a treat, the book is sprinkled with delightful historical menus that capture the eye and entice the appetite (though unfortunately only four of the 10 restaurants discussed are still open). Paste caught up with Professor Freedman, gaining further insight into restaurant’s flavorful past, and how social media factors into food’s future.

Paste: At Yale you teach Medieval History, with a focus on peasantry. How did you go from studying the Middle Ages to modern dining?

Paul Freedman: I’ve always been interested in class and markers of class, and when I worked on Medieval peasants I was interested in types of the lowly food that they ate—gruel, dairy products, root vegetables – which were held in contempt by the aristocracy. Then I wrote a book on spices, which were the quintessential prestigious food of the Middle Ages. That was the bridge to Medieval Food. I became interested with what people of different classes eat, what people of different ethnicities eat, and even more the stereotypes they make of what other people eat. When I was working on the spice book, I had a fellowship in the New York Public Library Cullman Center and I saw an exhibit of their menus—they have this huge menu collection—menus from New York City, going back to 1840. They entranced me.

Paste: In the book, you explore the mystery of how to define American food. Did you come up with a definition?

PF: I think so. There are several forces that interact to form the kind of food that we eat today. One is a love of variety, and you see that in the popularity of “ethnic” food. In the proliferation of brands, even of not all that great mass-market industrial product, they always come in flavors and variety. Another characteristic is regionalism and the waning of regionalism. There are American regional cuisines, but they tend to become homogenized into a national standardized pattern. And that national standardized pattern is what I think of as modern cuisine – when people stop making their own bread, when bakeries become uncommon, when people buy Wonderbread or the more sophisticated version – whatever it is, it’s a packaged product. If I were to go on with this investigation of American food, I think I’d divide it into what used to be called “ethnic” cuisine, regionalism, and modernity standard.

Paste: How would the current “foodie” culture fit into your study?

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-