Confessions of a Wannabe Internet Psychiatrist

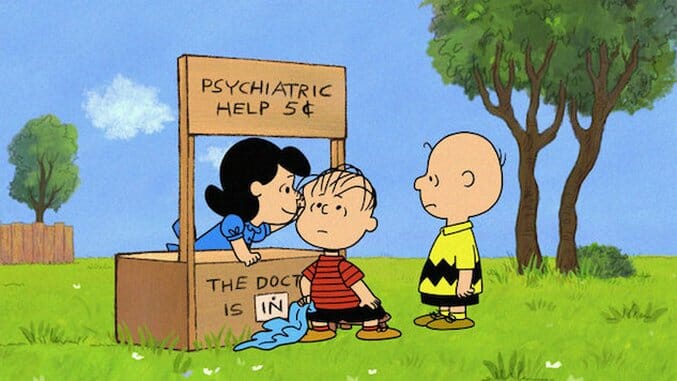

Image: FOX

One of my main goals as a writer is to help people through the power of words, and mental health is an area I happen to know intimately.

Like a lot of people, I diagnosed myself with the help of WebMD’s symptom checker and a number of online quizzes. Obviously that wasn’t enough, and both a psychologist and psychiatrist came to the same consensus. Ten years later, I consider myself a veteran and have developed a habit of giving anyone with less experience than me mental health advice, or as others call it, “wanting to be a psychologist.” I’ve even written a few Paste stories on it.

These days, it seems like nearly everyone on the internet experiences some form of mental illness—the truth is that more people are opening up about it in an era where public communication is as easy as firing out a fleeting tweet. Whether it was intended or not, social media has fostered a massive community for those with mood disorders. Everyone on Twitter, for example, seems to have some derivative of mental illness, which probably explains why the network has become an epicenter for Trump-era self-care. The discussion on mental illness has dramatically amplified, especially with the presence of figures like Carrie Fisher and Chance the Rapper. It’s uplifting to know that someone with the exact same (or similar) plight not only admits it, but also helps nullify the stigma. We see people #TalkingAboutIt, so we follow suit.

The problem is that experience does not convey authority. It’s great to be open about an illness, but it’s more important to be right. Around 80 percent of internet users self-diagnose through the internet. Once we’ve figured out the problem, we’re less likely to agree with a dissenting diagnosis, even if it comes from a professional. Self-diagnosis “undermines the role of the doctor,” Srini Pillay, M.D. explains via Psychology Today. “We can know and see ourselves, but sometimes, we need a mirror to see ourselves more clearly. The doctor is that mirror.”

When we equate our hypotheses with a professional diagnosis, we’re also putting others at risk. Wannabe internet psychiatrists are likely experts on their own experience with these disorders, but people aren’t uniform, meaning that one coping strategy could exacerbate someone else’s illness.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-