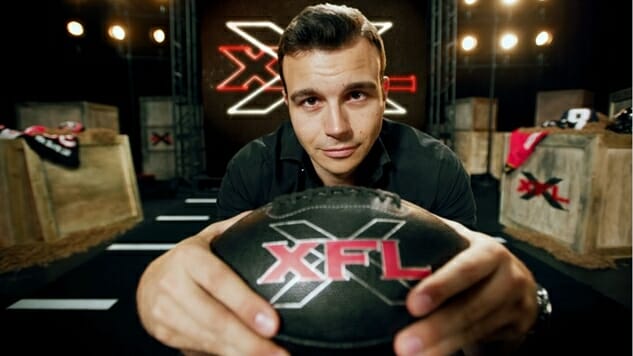

Charlie Ebersol on the NFL, Vince McMahon, and His New 30 for 30 Documentary: This Was the XFL

Photo by The Company

Dick Ebersol is effectively the father of NBC Sports, and he developed Saturday Night Live with Lorne Michaels. Raised by one of the world’s foremost experts on television, Charlie Ebersol is blazing his own trail through the media landscape—from producing Shaun White: Don’t Look Down, a 2006 documentary about the Olympic Gold Medalist snowboarder, to co-creating both a yearly special on USA Network where NFL players open up about their struggles, called NFL Characters Unite, and The Profit—a reality show on CNBC with Marcus Lemonis, which finished its 4th season in November.

Ebersol’s newest project takes on the challenge of matching the gold standard that has become ESPN’s 30 for 30 brand with This Was the XFL, premiering tonight on ESPN (initially there were only 30 documentaries planned as a celebration of ESPN’s 30th anniversary—hence “30 for 30,” but they became so popular that ESPN just keeps churning them out).

These documentaries were championed into existence by Connor Schell of ESPN Films, and America’s first national sports blogger/former ESPN employee, Bill Simmons (AKA, He Who Shall Not Be Named in some portions of ESPN’s executive offices). The idea was simple: give knowledgeable and passionate directors the space they needed to tell a story in the world of sports. Nearly every 30 for 30 documentary is a home run, with lessons that reverberate far past the playing field, so there is plenty of pressure on this crew to produce with such a charged topic like the football pirate ship that was the XFL.

Dick Ebersol and Vince McMahon lead the 50-50 XFL ownership split between NBC and the WWF (which since has been renamed the WWE). Now, sixteen years later, Charlie is back to examine the collapse of the XFL, and explain how the brash league changed sports forever.

The following interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Paste: Why should the XFL still be relevant in 2017?

Ebersol: Well first of all, you can’t watch a professional sporting event without seeing the XFL even today. The advent of the sky-cam and the steady-cams on the field and miking the players, I mean more generally the idea of access—that the television audience has to be granted something different than the live audience for it to really matter. That was all invented by and for the XFL.

The league itself reinvented the way professional leagues spoke to their audiences, and really if you look at what’s going on right now with the NFL, and professional baseball, and hockey, who are struggling to communicate in many ways with their audiences, the need for a reminder of what it is to make a league that is by and for fans, is enormously important.

I think the other thing is: it’s good to laugh, and this is a ludicrously silly story in a lot of ways, and I think that this film hopefully captures that hilarity.

Photo by Todd Warshaw/Getty

Paste: Do you ever see another competitor to the NFL emerging?

Ebersol: I think you’re going to see another one soon. Every 15 years, somebody seems to come along with enough money—the USFL in the early 80s, the XFL in the early 2000s—I think we’re probably due in the next couple of years. I know Tom Brady’s agent right now is trying to launch his own version of a league. At the end of the day, the NFL is so big that it becomes difficult to really create a product that all of its fans want. And also, it’s so mainstream that somebody who comes along with an appropriate counter-cultural movement I think will have a lot of success.

All you have to do is look at the success of the UFC, and what it did over the last 15 years against professional boxing, to realize that there’s clearly space in this media landscape for someone to come along with a new sports league.

Paste: So where in the media landscape do you think it would fit? Would an internet company bring it on, or are there TV networks that might be interested in competing with the NFL?

Ebersol: I think all the television stations are desperate to figure out how to have live events, because it’s the only thing that really translates, and the only thing that aggregates a real audience. So, I think that as cable is falling apart, and they’re losing a lot viewers and broadcasters are as well, the need for more appointment viewing—live event viewing, is increasing exponentially every year. So, I think that as that sort of downward spiral occurs, a lot of the primary broadcasters are looking for it.

Also, I don’t think anyone’s really figured out how to aggregate an audience at the same time online. Which, advertisers need that. General Motors, or more importantly—Hollywood when they’re advertising a movie—it doesn’t help them if you’ve got a fragmented audience over the course of several weeks. They need you to have everybody there at the same time so they can deliver their messaging right then, and they haven’t figured it out online. So, I do think that the Snapchat’s and the Twitter’s and the Facebook’s and the Instagram’s of the world are all looking for giant events that can pull everybody together, and professional football is the one professional sport that is tailor-made for television.

Photo by Todd Warshaw/Getty

Paste: The MLB, NHL, and NBA all have this direct-to-consumer broadcast model—where you pay a yearly subscription to the league and it allows you to access any live game from an internet connection, and the NFL only does something similar in a roundabout way through DirecTV. But with the NFL moving more games online—like broadcasting Thursday Night Football on Twitter—do you see that as part of a larger move towards that type of direct-to-consumer broadcast model, or are they just kicking the tires on this idea?

Ebersol: I think they’re still trying to figure it out. The other sports leagues—they have big deals. The NBA has a big deal, but the NBA is a rounding error compared to what the NFL’s deal is. Their media partners alone are paying them close to 12 billion dollars. They’re not really rushing off to what is still effectively a very unknown business model. I don’t think anyone’s really figured out how to monetize online video in a consistent and meaningful way enough that they could justify taking on the NFL.

That being said—in 1994, FOX was a startup broadcast network and everybody said they wouldn’t be able to pull it together, and along comes the NFL validating their system and boom—FOX overnight becomes a genuine broadcaster. I think the NFL is cautious about what partner they take on to do this, but I do think that they’re kingmakers to a large degree, and if they can figure out which platform provides the best entry point into it, they’re going to meaningfully alter the landscape.

Paste: That’s interesting, because it seems like we hear more often from the TV network’s point of view—as far as how much power over eyeballs they have, but a diehard fan like me will watch the NFL wherever they broadcast it. It doesn’t matter, it could be on Chinese state television, but I’ll still find a way.

Ebersol: And that was the whole point as to why the XFL got created. Because the NFL was so adamant about how big they were that they started charging networks a ridiculous amount of money. In 1998, when NBC walked away from the contracts because of how big and ridiculous they were, CBS and FOX signed up for deals that made them lose a hundred million dollars a year. So they’re paying four or five hundred million dollars a year, and losing a hundred because they can’t pay back the expense of advertising money.

That’s why the XFL got created because NBC and my dad just said look, this is ridiculous and this is not a pattern that’s going to subside anytime soon. The NFL is going to continue to double down and require these payments, and they can’t sustain it. And so to your point, I think the networks fancy themselves as being in control, but in reality: they don’t own the NFL. They have to pay license fees. They have to renegotiate with the NFL every four years, and that renegotiation is incredibly costly. I think NBC is going to write down like a billion dollars on Sunday Night Football. Which is the most successful—in terms of audience—it’s the most successful show in all of television, and yet they’re losing a billion dollars a year.

Do you think that American Idol would stay on the air if they were losing a billion dollars a year in order to put it on the air?

Paste: Yeah, good point. The amount of money that we’re talking with the NFL, it’s just monopoly money at this point.

Ebersol: 100 percent.

Paste: Pivoting back to the XFL, imagine you were in charge when it launched. Looking back, is there a specific thing you’d have done differently?

Ebersol: Al Luginbill—head coach of the Los Angeles Xtreme—I would have hired him as the head of football operations, instead of the guys that they did hire.

Photo of Al Luginbill by Tom Hauck/Getty

Because I think that Al really liked the idea of launching a new football league, and was very open to creating really meaningful change in the game to make it more interesting, which is why he won the championship. The guys they did hire who ran operations were very interested in getting jobs in the NFL afterwards, and so they didn’t want to do anything too out of the box—which was a huge problem because Vince, my dad, NBC and the WWE were selling a very specific, giant marketing opportunity. Meanwhile, the XFL—the football league—was mediocre football that was not well-thought out, and the players only had 28 days to practice, because the guys who were running operations didn’t take it seriously. So, if I was going to make any changes, they’d all be there.

Paste: Do you see any influence in the XFL from the USFL?

Ebersol: The USFL was very closely examined, in particular, by my dad as to what not to do. The USFL was basically just a cheap knockoff of the NFL. They were a handful of billionaires who wanted to be in the NFL, but the NFL wouldn’t let them in—people like Donald Trump. So, they created their own league and spent millions and millions and millions of dollars trying to compete with the NFL, and eventually got stepped on. And it’s why no one really remembers the USFL because really nothing that interesting happened—other than a bunch of guys who when it folded, went to the NFL and had huge careers.

The XFL was meant to be—from the ground up—something different and really built for television. So, all the stuff that got created from the XFL that translated into the modern television experience—the sky-cam, the steady-cam interviewing players—all that stuff, that was all because the guys creating it were first and foremost, television guys. The other part that was really meaningful was there was only one billionaire involved, and it was Vince McMahon who is a self-made genius.

And he understood that if they owned everything top-down, all the teams, all the players, all the coaches—everybody was an employee of the league, as opposed to individual owners—they could really control the quality of play, and who was where and all that kind of stuff. Which lead to a much more even-handed business model that really could’ve supported for years and years if the primetime games hadn’t been so disastrous. I think in reality, the XFL probably would have had several years of success if it had time to mature properly.

Paste:Paste just launched a wrestling section, so I’d be remiss if I didn’t ask, what’s Vince McMahon like? Is he anything like the character that we see on TV?

Ebersol: He’s nothing like the character you see on TV. I’ve known Vince since I was four years old when my dad and Vince created Saturday Night’s Main Event together. And I grew up with him and my father, and the defining characteristic of Vince and my dad is that who they are in the press and in the public is not who they are. And I think that this film—more than anything really is intended—or I think does open up a version of Vince that no one’s seen before, largely because I’ve known him for 30 years. So what he gave me in interviewing—who he was as we sort of broke down what this thing was—was a lot deeper, and a lot more pensive and emotional than people are expecting.

The last couple minutes of the film—I don’t want to give up the end—but are very very emotional. It’s a conversation between my dad and Vince and nobody else. And it’s definitely a version of Vince McMahon that nobody’s ever seen before. It’s Vince without the wrestling mask.

Photo of Vince McMahon and Dick Ebersol by ESPN Films

Paste: Well, personally, I’m excited for the film. One of the bigger fights I can remember having with my parents as a kid was over whether I could get a “He Hate Me” jersey. I remember thinking it was just the coolest thing ever when it launched. I was kind of the perfect age group for the XFL. I grew up loving football and watching the WWF, so a league that intended to break all the rules was just thrilling for a kid like me.

Ebersol: He Hate Me jerseys are online, you can buy one right now. They’ve got authentic jerseys. And that was the thing. They just basically said “everything’s on the table. You can change and do anything you want.” And by doing that, they opened up the floodgates to really innovative and dangerous and cool and interesting and bizarre things, and I think that really lead to altering the landscape of production in television, marketing and player relationships, and I think we could use a little bit more of that today.

I think a lot of people would agree with you (being in the target demographic)—that was in large part the premise that worked the most about it.

Paste: Unfortunately it seems like the NFL is almost doing the opposite, where they’re only reacting to everything. Now it’s just this weird bureaucratic structure.

Ebersol: Yeah, it’s a complicated mess. Because on so many levels you’re talking about a product that by its nature had to be controversial, but in reality, was just giving the fans what they actually wanted. I think This Was the XFL hopefully gets to the heart of that, which is: people wanted to talk about how controversial it was, but at the same time, when you look at the fundamentals, it was sort of a no-brainer.

Jacob Weindling is Paste’s business and media editor, as well as a staff writer for politics. Follow him on Twitter at @Jakeweindling.