The 100 Best Movies of the 1950s

While the passing decades have distilled critical opinion to a fairly reliable “Required Viewing” roster for the best 1950s movies, the era remains more difficult to pin down than the 1930s or ’40s, largely due to an explosive diversity in both subject matter and cinematic technology. We still see the profound influence of WWII, we still see film noir and Westerns and the development of European neorealism. We also see the proliferation of color technology. The affluence that grew in the post-war years and the rise of “leisure culture” play a role in the zeitgeist of this decade. There is also an emphasis on teen culture, perhaps best represented by the brief but meteoric career of James Dean. Television became mainstream, and Hollywood found itself with some stiff competition from the networks. Cold War paranoia and anti-Communist sentiment joined with a profusion of new technologies to fuel American film—science fiction and “outer space” films, in particular. It was the decade of Alfred Hitchcock and Ingmar Bergman, and in Asia, Akira Kurosawa and Satayajit Ray were both producing some of their finest work. The French New Wave was in full flow, with directors such as Jean-Luc Godard and Francois Truffaut defining what would come to be known as auteur theory. Psychological thrillers, Shakespeare adaptations, goofy musicals, and the “cast of millions” epic style canonized by Cecil B. deMille are all very much in evidence. Film took off in a million directions during the 1950s, and it is truly up for debate what constitutes the “best” of this prolific and diverse decade. So we’ve tried to keep an eye on the films that defined something about the era, and while anyone might squabble over one being more artistically important than another (rightly so, in some cases), we’ve pulled together a list of films that all tick the “if you want to consider yourself a culturally literate cinephile, you need to see this” box for one reason or another.

Here are the best movies of the 1950s:

100. The Tingler (1959)

For William Castle, going to the movies was a matter of life and death. Or at least he wanted to convince you as much: If he didn’t have you believing you had some serious stakes in what was happening onscreen, then he—the 20th century’s consummate cinematic showman—wasn’t doing his job. So begins The Tingler, Castle’s 1959 creature feature, wherein Castle appears on screen like a B-grade Alfred Hitchcock to remind the audience that what they’re about to see is hardly a lark. Fear is a natural but serious affliction, a building up of poisonous humors within one’s nervous system, and so it must be addressed should you endure the film he’s about to show you. The only way to live through The Tingler? You’re going to have to scream. And, to prove his medical conclusions, Castle introduces us to Dr. Chapin (Vincent Price at the height of his weirdo sophisticate phase), a man who believes that every human being has a parasite living in their spine that feeds off of extreme fear—that’s the “tingling” sensation you get every time you’re panicked. The parasite will grow and decimate a person’s backbone unless it’s defeated/deflated by the only logical reaction to fear: screaming. Things of course get tinglier once Chapin captures an actual rubbery spine centipede—and, meanwhile, Castle was always ready to exploit his audience’s squirm factor, having “Percepto!” contraptions installed into each theater seat, set to buzz the butts of already agitated film-goers to scare them into thinking the insectoid creature was crawling between their legs. Among Castle’s many interactive “gimmick” films in the 1950s, The Tingler might be the Castle-est, a sincerely wacky, unsettling, imaginative experience whether you’re equipped with a vibrating chair or not. And hearing Vincent Price hollering into the void of a pitch-black screen, “Scream! Scream for your lives! The Tingler is loose in the theater!”, offers enough urgency to convince you something may be nipping at your backside after all. —Dom Sinacola

99. The Ten Commandments (1956)

There are a lot of major motion pictures from the ’50s that remain eminently relevant and even bizarrely au courant. The Ten Commandments isn’t one of them, But even though it feels dated, from the standpoint of cultural literacy it remains a must-see. Luckily, it hits the airwaves every year around Easter/Passover, and has done since 1973, so it’s easy to catch. Cecil B. DeMille’s remake of his own 1923 treatment of the same story is the dictionary definition of “epic” with its sweeping, massive set, mind-boggling cast, and overall Big Damn Production. It’s overblown, even a little ludicrous, but at the same time, this story of Moses’ liberation of the Hebrews from Egypt has a certain magnificence that only DeMille could have given it. It’s incredibly extravagant and runs four hours, so prepare to arrange some intermissions if you must. You might giggle at some quaint or dated or kind of pompous moments but you won’t be bored. It takes a big story, gives it a cast of stars (Charlton Heston, Yul Brynner, Edward G. Robinson, Vincent Price, Anne Baxter and Debra Padgett for starters), and gives it an opulent, sprawling, color-saturated, mind-blowingly excessive field on which to play that story out. It’s eye-popping and a genuine spectacle. —Amy Glynn

98. Lola Montes (1955)

Way back in the early 2000s, the films of German-born, Paris-based director Max Ophuls languished out of print. His fin de siècle Europe, aristocratic mores, women on the verge of nervous breakdowns and loooooong tracking shots fell out of sight. But with the availability of the fever dream of his financially and critically catastrophic last feature, Lola Montès, our portrait of the artist in his final years is complete. Eliza Rosanna Gilbert—a dancer and actress most often called by her stage name, Lola Montès—pioneered the “cult of celebrity.” Paramour to composers Franz Liszt, Frederic Chopin and Richard Wagner, not to mention numerous dukes, counts and even King Ludwig I of Bavaria, her affairs were fodder for the papers, and sometimes cause for riots. Ophuls anticipates such modern media circuses, eschewing simple biography for his heroine and setting her in a context more grandiose and garish: a real circus. —Andy Beta

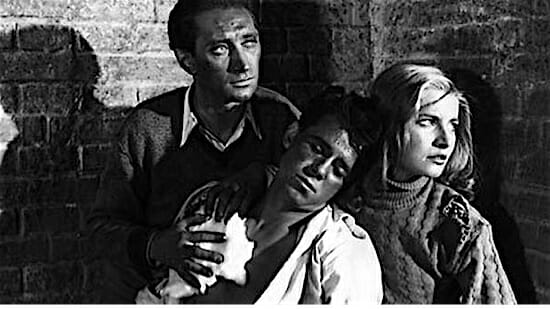

97. Kanal (1957)

“Watch them closely, for these are the last hours of their lives.” The voiceover that opens Kanal, which simultaneously introduces us to a depleted company of the failed Warsaw uprising and foretells of its imminent grisly fate, powers Andrzej Wajda’s “resistance” movie with a morbid fascination. Aware of their slim chances of survival with the German army tightening its grip all the time, the remaining men and women of Lt. Zadra’s Home Army unit escape to the sewers, not because they think that offers much chance of survival, but because their instincts keep driving them to live, even if just for a few moments more. But the confusion and strange terror down there, in the foul winding tunnels of an underground maze of waste, make them a pitiful few last hours. All sense of time and geography is lost: it’s just mysterious bodies, wading in perpetual night through a river of shit. Sandwiched between A Generation and Ashes and Diamonds, as the least complicated and political of Wajda’s war trilogy, Kanal is as pure a portrayal of human desperation as one might find in the cinema. —Brogan Morris

96. Les Enfants Terribles (1952)

Jean Cocteau adapted this screenplay from his own novel and Pierre Melville directed. A tale of mind games and manipulations, it features Cocteau’s dreamlike, poetic sensibility and Melville’s lucid, deft direction. Edouard Dermit plays Paul, a sensitive young man who’s a bit obsessed with a girl named Agathe (Renee Cosima), to the consternation of Paul’s sister Elisabeth, who has a rather inappropriate fascination with her brother. Cosima also plays (in drag) school bully Dargelos, who sees to it Elisabeth gets her karmic just desserts after jealousy leads her to thwart the romance between her brother and Agathe. It’s fantastical in tone, with Cocteau’s typical poetry-infused visual sensibility. He also provides the narration, which some critics have found to be a bit over the top—in any event the overall impression is that while Melville might have directed it, this is really Cocteau’s film. It’s strange and dreamy and full of adolescent angst. Probably not the finest work of either Melville or Cocteau, Les Enfants Terribles remains an intriguing collaboration between two masters of mid-century French cinema. —Amy Glynn

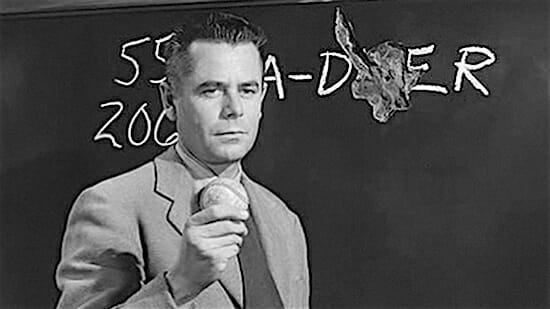

95. Blackboard Jungle (1955)

Richard Brooks’ glorified after-school special is fascinating for the film it could’ve been: something truly subversive, an indictment of America’s post-war social systems and a loud screed against systemic racism. Instead, Blackboard Jungle is a movie divided, willing to confront some serious issues but unwilling to make much noise about it. Preluded by a title card warning that the film isn’t about all public schools, but is rather a look at the rising tide of juvenile delinquency spreading into some public schools, the film from its very first moments shifts blame to the kids acting out, diluting deeper messages about the broken systems which failed, and continue to fail, these kids in the first place. After all, a young teacher (Glenn Ford) with an expecting wife believes that every kid deserves a shot at a good education, but after his wife ends up in the hospital due to some harassment care of a few hooligans unafraid to go too far, he must admit that some bad apples are just straight-up rotten. Sidney Poitier stars in one of his first films as an ally to the beleaguered teacher, and Ford is predictably committed to the melodrama, but the film shines in its subtler details—the use of Bill Haley’s “Rock Around the Clock” to signal the dawn of a youthful revolution, or the majority of the school’s teachers being WWII veterans returned to a country which doesn’t seem to appreciate them—pointing to a much thornier film in Blackboard Jungle’s marrow. —Dom Sinacola

94. Ace in the Hole (1951)

Billy Wilder’s cynical streak is a mile wide in this story of muckraker journalist Chuck Tatum, who plots an amoral scheme to take advantage of a collapsed mine incident in the deserts of New Mexico. Starring Kirk Douglas in full snarling villain mode, it’s a film that looks squarely at the relationship between the press and public calamities that allow it to sell papers. If you have any preconceived notions about ’50s movies being wholesome, Ace in the Hole will soon put those to bed.

93. Curse of Frankenstein (1957)

The presence of color, glorious color, is an overlooked moment in the evolution of horror cinema, but 1957’s Curse of Frankenstein is one of its most important moments. After years of the classic Universal monsters being absent from the spotlight, Hammer Film Productions chose to bring the greatest of them—Frankenstein’s Monster—back to life in a manner that fit the times and once again put the fear of God into audiences. And it’s the richness of the color—the red of arterial blood, the vivid green of Dr. Frankenstein’s traveling cloak, the blue of a dark, shadowy laboratory—that helped create Hammer’s signature vibe, dripping with gothic opulence and grandeur. The roles here are also reversed: The monster this time around (Christopher Lee) is presented as dangerous but more or less thoughtless, an unfortunate automaton who is less than the sum of his stitched-together parts. The true monster is Dr. Frankenstein himself, masterfully played by an imperious Peter Cushing. His blithe disregard for ethics, his own life and the lives of his friends are an obvious influence on the caddish, antihero scientists who came after, such as Jeffrey Combs’ Herbert West in 1985’s Re-Animator. Unlike Colin Clive in the 1931 Universal original, Cushing would never be mortified by the results of “tampering in God’s domain.” Each discovery only pushes him to go further, deeper into his own damnation. —Jim Vorel

92. A Star is Born (1954)

Judy Garland proves her nuance and dramatic skill in this archetypal Hollywood tale of rags-to-riches stardom. The story is practically written into the movie industry’s DNA—originally called What Price Hollywood?, the first version was made in 1932. Even with three iterations (and one more on the way, starring Lady Gaga and Bradley Cooper), the ’50s version is still likely the finest. Garland is Esther Blodgett, a homely small-town aspiring singer who is groomed and manicured into a perfect ingenue. But her enormous talent soon eclipses her beloved mentor, James Mason. Mason, a washed-up lush who is hopelessly in love with her. Almost Shakespearean in its tragedy—and in its epic length—A Star is Born is essential viewing.

91. Picnic (1956)

There are only two plots in all of storytelling. One is “a hero sets out on a quest.” This is the other one: “A stranger comes to town.” This film, adapted from William Inge’s Pulitzer-winning play of the same name, depicts 24 hours in the life of a sleepy Kansas town during which several peoples’ lives are turned upside down by the arrival of chaos in the form of Hal Carter (William Holden), a down-on-his-luck former football star who’s passing through to connect with his old friend, Alan Benson (Cliff Robertson). He meets the Owens family (Kim Novak, Betty Field, Susan Strasburg) and their spinster-lodger Rosemary (Rosalind Russell) and sparks begin to fly. The movie is sweet and sad and angry and nostalgic and dreary all at once, and it put Kim Novak on the Hollywood map—all good things. But the takeaway is that ultra-sexy can happen without anyone even touching. The dance scene between Holden and Novak, set to the gorgeous strains of “Moonglow,” is as steamy today as it was in 1955. —Amy Glynn

90. Black Orpheus (1959)

The Greek myth of Orpheus and Eurydice has been the source of countless works of art over the centuries. Marcel Camus’ adaptation is set in a Rio de Janeiro favela and features a brilliant soundtrack by Tom Jobim and Luiz Bonfa. Brenno Melo plays Orfeu, a talented guitarist in a somewhat reluctant engagement to Mira (Lourdes de Olveira) who falls in love with Eurydice (Marpessa Dawn). Eurydice is taken from him by Death. Orfeu tries to get her back, fails, and is killed by the jilted Mira. It’s an ancient story and Camus does a marvelous job of making it new and fresh in its recontextualization. The samba and bossa nova music are befitting of mythology’s greatest singer-songwriter, and the production is stylish and colorful and full of heart. Visually lush and ebullient, this is a film to roll around in, not to be overly cerebral about. Lavishly sensuous, with stunning cinematography and a soundtrack to die for (and come back from Hades to hear all over again). —Amy Glynn

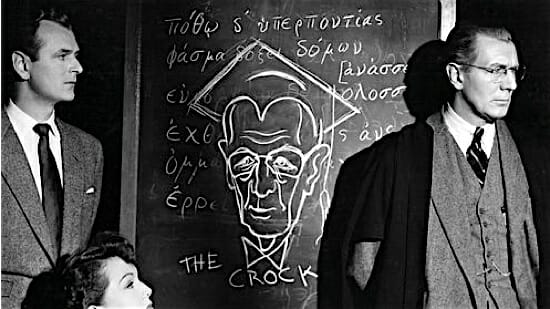

89. The Browning Version (1951)

Anthony Asquith directed this adaptation of a stage play by killer British playwright Terence Rattigan, who also supplied the screenplay. Together they afforded Michael Redgrave what just might be his best performance ever. The story of a boarding school teacher whose life goes into freefall is one of the great-granddaddies of the Teacher Who Actually Schools You that has become one of the tropes that never gets old (Lookin’ at you, Stand and Deliver!). The great strengths here are absolutely the script and Redgrave’s performance-he does as spectacular job with what is actually a pretty dreary subject: Life falling apart. He breathes life into a potentially airless character and his performance is riveting. —Amy Glynn

88. Night and Fog (1956)

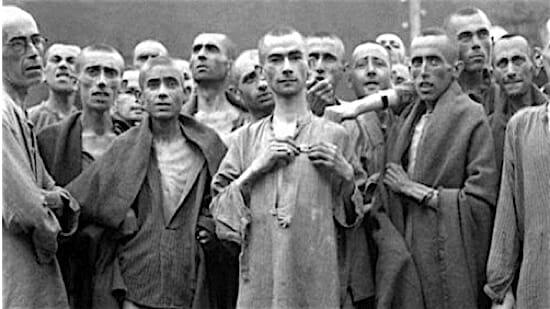

Released 10 years after the liberation of prisoners from the Nazi concentration camps, Night and Fog was almost never made. Any number of reasons contributed to its tenuous birth: that noted documentary director Alain Resnais refused repeated attempts to helm the movie, insisting that a survivor of the camps be intimately involved, until screenwriter Jean Cayrol came on board, himself a survivor of the Mauthausen-Gusen camp; that Resnais and collaborators battled both French and German censors upon potential Cannes release; or that both Resnais and Cayrol themselves struggled with especially graphic footage, unsure of how to properly and comprehensively depict the unmitigated horror of what they were undertaking. Regardless, the film found release and is today, even at only 31 minutes, an eviscerating account of life in the camps: their origins, their architecture and their inner-workings.

Yet, most of all, Night and Fog is a paean to the power of art to shake history down to its foundational precedents. Look only to its final moments, in which, over images of the dead, emaciated and piled endlessly in mass graves, narrator Michel Bouquet simply asks to know who is responsible. Who did this? Who allowed this to happen? Which is so subtly subversive—especially given the film’s quiet filming of Auschwitz and Majdanek, overgrown and abandoned, accompanied by lyrical musings and a strangely buoyant score—because rarely do documentaries demand such answers. Rarely do documentaries ask such questions. Rarely is truth taken to task, bled of all subjectivity, and placed naked before the audience: Here is evil, undeniably—what will you do about this? —Dom Sinacola

87. East Of Eden (1955)

Elia Kazan’s adaptation of the Steinbeck novel of the same name might be most famous for being the film that launched the brief but meteoric career of James Dean. A cheery little Cain and Abel story set in the lettuce-farming country of California’s Salinas Valley, the film garnered intense critical acclaim for Kazan’s masterful use of CinemaScope technology to create a beautiful, moody mise en scene. Critical opinion was divided on Dean, whom some found pointlessly histrionic. Others have pronounced his fiery confrontations with his pious father (Raymond Massey) to be compelling and masterful. Whichever way you see it, there’s strong consensus that this film created the persona of disaffected bad-boy Dean, whose iconic rebelliousness defined teenage rebellion and the generational divide that widened into the 1960s. —Amy Glynn

86. Horror of Dracula (1958)

Horror of Dracula is either the second or third most iconic “classic vampire” film ever made, trailing only the 1931 Bela Lugosi Dracula and possibly the original Nosferatu. But really, if you were going to put together the ultimate, time-spanning Dracula film, you’d choose this version of the vampire, as played by the regal, intimidating Christopher Lee at the height of his powers. Horror of Dracula is simply a gorgeous movie, with lush, gothic settings—crypts, foggy graveyards and stately manors—photographed with the Golden Age charm of Technicolor. It has the best version of Van Helsing ever put to film (the aquiline, gaunt-looking Peter Cushing), some of the best sets and an omnipresent feeling of refinement and grandeur. Dracula, as played by Lee, is a creature of dualities—preferring to use very few words and simply influence through his magnetic presence, but also just moments away from leaping into action with ferocious animality. Along with Curse of Frankenstein, it’s the film most responsible for the late ’50s to early ’70s revival of classic gothic horror via Hammer Film Productions in the UK, which would produce dozens of takes on Frankenstein, The Mummy, and no fewer than eight Dracula sequels. The first, however, is unquestionably the best—so effective that it typecast Christopher Lee as a horror icon for decades, exactly as Dracula did to Bela Lugosi. —Jim Vorel

85. Father of the Bride (1950)

DNA tests have not been conclusive, but this Vicente Minelli comedy is possibly also the father of Nora Ephron and John Hughes. A nostalgia-bomb comedy about an anxious father (Spencer Tracy) coming to terms with the fact that his baby (Elizabeth Taylor) is not a baby anymore. The film might seem like a bit of a lightweight, but it’s worth noting it received Oscar nominations for Best Actor, Best Screenplay and Best Picture. It’s a warmhearted and funny look at parent-child control struggle, anxiety, and confronting the need to let go, and a poignant picture of family life in the postwar United States. It’s not necessarily an epiphany—just a really well done classic comedy with great writing, great acting, and surefooted direction. —Amy Glynn

84. Throne of Blood (1957)

In adapting Macbeth from Scotland to feudal Japan, Akira Kurosawa visually inflected his version with an evocatively chilly ambience—especially with its preponderance of fog and that seemingly isolated castle in the mountains—that gives William Shakespeare’s tragedy of ambition run amok the feel of a horror movie. He also brought elements of Noh theater into the mix—seen in its ceremonial set designs, Masaru Sato’s use of flute and drum in his score, and especially in the deliberately affectless performance styles of Isuzu Yamada and Chieko Naniwa—that has the effect of giving Throne of Blood a ritualized feel, a sense of haunting inevitability. In Kurosawa’s hands, one hardly needs Shakespeare’s own language to experience the horrifying poetry of Washizu’s (Toshiro Mifune) inexorable path toward his own personal doom, imprisoned not just by greed, but also by fear, guilt and heavens-defying egotism. Here is one of cinema’s rare shining examples of a great director transforming a great play and making it indelibly his own. —Kenji Fujishima

83. The Man Who Knew Too Much (1956)

Six words: James Stewart, James Stewart, James Stewart. Man, that guy was pitch perfect in pretty much everything, but put this jewel in the setting of a classic Hitchcock noir and you are in for a treat. Hitchcock made this film as a Technicolor reboot of his own 1934 treatment of the same story. Critical debate continues to percolate over which version is better. Hitch famously quipped “Let’s say the first version is the work of a talented amateur and the second was made by a professional.” It took the Oscar for best song and left Doris Day’s rendition of “Que Sera, Sera” permanently imprinted on American cultural vernacular. Some might call this a laconically paced thriller, but Hitchcock took the time to make ample use of the wonderful settings afforded by shooting on location in Morocco, and elicits wonderful performances from the whole cast. For a Hitchcock movie this one’s got a relatively high number of slow moments, but the last act’s a masterful thrill-ride and the rest of the time, Hitchcock’s beautiful compositional sense and the superb acting are more than enough to hold your interest. —Amy Glynn

82. Godzilla (1951)

It’s amazing, isn’t it, how something so seemingly childish and flat-out dopey on paper could be as substantive, and as enduring, as Ishiro Honda’s Godzilla? Hire a couple of actors and have them alternate donning an unwieldy rubber monster suit, and then let them stomp all over a miniature Tokyo set, smashing buildings with wild abandon, and presto: Just like that, you’ve made unexpected movie history. However silly Godzilla sounds when broken down into its component parts, it remains every bit as meaningful today as it did back in 1954, less than a decade after the U.S. of A. dropped nuclear ordnance on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, a colossal and nightmarish metaphor for the horrors of nuclear warfare. The King of the Monsters’ first major outing spawned legions of imitators and about as many sequels and spin-offs and reboots—we’re still making Godzilla movies, after all, and will continue to if Warner Bros. has anything to say about it – but there’s only one Godzilla movie that matters, Honda’s, a film awash in the fears of a nation and ablaze with radioactive nihilism. —Andy Crump

81. Othello (1951)

So, Orson Welles was a supergenius. And studios just hated the guy. He was beset with financial tribulations and pull-outs and bait and switches and catfights every time he got behind a camera. He might be one of cinema’s most enduring examples of creativity being generated by constraint, sometimes perhaps more than it is by unfettered freedom. Welles’ Othello is arguably mandatory viewing for anyone who wants to make a movie on a shoestring budget. It took four years (and three Desdemonas) to make this movie because he couldn’t secure studio backing and would shott until he ran out of dough, then resume when he’d scored a few acting gigs. It was ridiculous and a testament to Welles’ genius or the existence of miracles or both that the film isn’t an epic disaster. On the contrary—it’s fascinating. Many Shakespeare adaptations of this decade focused on extreme faithfulness to the original scripts—Welles cut Othello down to a zero-body-fat 92 minutes. The film uses fast, choppy cuts and intriguing angles to produce a quite Expressionist version of Shakespeare’s tragedy, and it doesn’t look remotely accidental or like the product of a production that stopped and started repeatedly over an agonizing four years. Welles himself is a wonderful Othello, and Suzanne Cloutier as Desdemona matches his energy beautifully, but the real star here is the directorial moxie and quick-wittedness and sheer tenacity of vision that got the thing onscreen. Welles fought hard for this movie and the result is a beautiful and fascinating take on one of Shakespeare’s darkest plays. —Amy Glynn

80. The Barefoot Contesssa (1954)

Long, long before Ina Garten was whipping up crabcakes on the Food Network, a nice young lady named Ava Gardner was emitting some serious BTUs as fictional Spanish sex symbol Maria Vargas. Down and out filmmaker discovers sizzling talent in Madrid nightclub, reignites his own career and starts hers, things happen, and Vargas ends up married to a count. There is much bling and sparkle and glam and a very unhappy ending. Joseph Mankiewicz’s original screenplay earned him an Oscar nomination and the film is considered one of the quintessential “Hollywood” high-glamor Golden Age films, although in fact it was entirely produced in in Italy. Critical opinion on the film was rather cleft when it was released: Some admired its decadence while others considered it exemplary of everything wrong with Hollywood culture, crass and unsubtle. I see it as a great meditation on Show Biz cynicism. What most folks agreed on was that Gardner was the hottest thing on celluloid. —Amy Glynn

79. Pather Panchali (1955)

Satyajit Ray’s Pather Panchali is, depending on who you ask, either the saddest movie ever made or one of the saddest, and if you don’t believe the former then you likely believe the latter (unless you are made of stone, but aside from rock golems and Republicans, people tend to be made of flesh and blood). But whether the film makes you weep more or less is, perhaps, besides the point. When we talk about the classics of cinema, we talk about influence, and one note worth making about influence is that it comes in all shapes and sizes: Some movies have impact on a micro scale, others on a macro scale. Pather Panchali’s influence may be best evinced on a micro scale, in specific relation to Indian cinema, presenting a watershed moment that sparked the Parallel Cinema movement and altered the texture of the country’s films forevermore.

This, again, isn’t proof of Pather Panchali’s actual substance, though let’s be realistic here: Ray’s masterpiece doesn’t need to prove anything to anyone. It’s extraordinary on its authentic artistic merits, an aching, vital movie crafted to transmute the harshest rigors of a childhood lived in rural India into narrative. Maybe it’s presumptuous for an American critic with no frame of reference for Pather Panchali’s cultural context to describe the film as “true to life,” but Ray is so good at capturing life with his camera that we come to know, to understand, the life of young Apu, regardless of who we are or where we come from, and isn’t that just the absolute definition of cinema’s transporting power? —Andy Crump

78. Les Diaboliques (1955)

Watching Henri-Georges Clouzot’s Les Diaboliques through the lens of the modern horror film, especially the slasher flick—replete with un-killable villain (check); ever-looming jump scares (check); and a “final girl” of sorts (check?)—one would not have to squint too hard to see a new genre coming into being. You could even make a case for Clouzot’s canonization in horror, but to take the film on only those terms would miss just how masterfully the iconic French director could wield tension. Nothing about Les Diaboliques dips into the scummy waters of cheap thrills: The tightly wound tale of two women, a fragile wife (Véra Clouzot) and severe mistress (Simone Signoret) to the same abusive man (Paul Meurisse), who conspire to kill him in order to both reel in the money rightfully owed the wife, and to rid the world of another asshole, Diaboliques may not end with a surprise outcome for those of us long inured to every modern thriller’s perfunctory twist, but it’s still a heart-squeezing two hours, a murder mystery executed flawlessly. That Clouzot preceded this film with The Wages of Fear and Le Corbeau seems as surprising as the film’s outcome: By the time he’d gotten to Les Diaboliques, the director’s grasp over pulpy crime stories and hard-nosed drama had become pretty much his brand. That the film ends with a warning to audiences to not give away the ending for others—perhaps Clouzot also helped invent the spoiler alert?—seems to make it clear that even the director knew he had something devilishly special on his hands. —Dom Sinacola

77. The Quiet Man (1952)

Seen today, John Ford’s 1952 Ireland-set comedy/drama/romance plays as both squarely of its time and enchantingly outside of it. On the minus side, there are its thorny gender politics. Though the female love interest, Mary Kate Danaher (Maureen O’Hara), exhibits a feistiness and a desire for agency that could be seen as proto-feminist to modern eyes, she’s ultimately put at the mercy of the hyper-masculine ex-boxer Sean Thornton (John Wayne), who is finally forced to tap into the violent side he’s so desperate to escape in order to consummate their marriage. The fact that Sean is an American—though of Irish origin, having been born in Innisfree, the village he returns to in the film—and Mary Kate a lifelong Irishwoman gives their dynamic a faint imperialist air as well. And yet, Ford, more often than not, disarms criticism by sheer virtue of his lyrical sensibility, reserves of deep feeling, and humane attention to character detail. The Technicolor Ireland of The Quiet Man is clearly a lush dreamscape: an out-of-time haven of hearty romance and even heartier community. Not that it’s a paradise, necessarily, as Sean finds himself stymied to some degree by Irish traditions that go against his much-more-forthright American upbringing. But this is not the dark and brutal vision of Ford’s later 1956 masterpiece The Searchers, with an outlaw outsider finding himself perpetually unable to fit into any established order. Here, in the looser-limbed and lighter-hearted The Quiet Man, Sean and the Irish locals eventually find common ground, albeit through a perversely extended brawl that plays as a purifying male-bonding session. —Kenji Fujishima

76. Witness for the Prosecution (1957)

A courtroom drama with noir leanings, based on a story by Agatha Christie and directed by the always-fascinating and sometimes really-damned-weird Billy Wilder? Yes, please. Tyrone Power’s last role was as accused murderer Leonard Vole, defended by barrister Sir Wilfred Robarts (Charles Laughton). He’s believed to have done in a besotted, wealthy widow, Emily French (Norma Varden) who’d been kind, or dotty, enough to make him the beneficiary in her will. Marlene Dietrich rounds things out as Vole’s wife, who both provides an alibi for her husband and testifies for the prosecution that the man admitted to the crime. Say it with me: Hijinks Ensue, Christie style. And if there was anyone who could match Christie for Twistedness factor, it was surely Billy Wilder. The surprise ending staggered audiences (and no, I’m not telling), the acting crackles with life from end to end (especially in Laughton’s case), and the mise en scene is fabulously dramatic. This is a master of suspense placed into the hands of a master or weirdness and subtlety and it is just plain riveting. —Amy Glynn

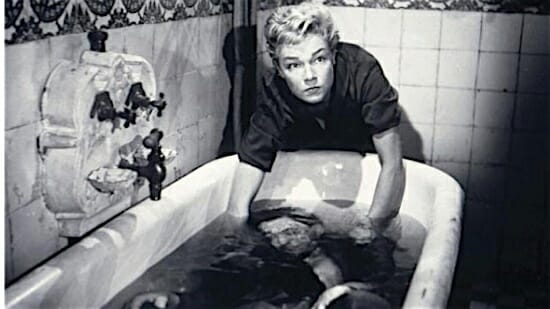

75. The Wild One (1952)

Marlon Brando—the whirling dervish and one-man force of nature who forever changed screen acting—had better roles than Johnny from The Wild One. But they didn’t often come cooler. The young, fulsome Brando is a pin-up dream in his leather biker jacket and hat, cruising through an unsuspecting and nervous town with his motorcycle gang. Feeding into fears of teenage juvenile delinquency of the era, The Wild One is essentially youthful drive-in movie fare. But the film is forever elevated by the pouting, menacing Brando, whose response to the question “Whaddya rebelling against, Johnny?” is as memorable as they come: “What have you got?” —Christina Newland

74. The War of the Worlds (1953)

To many this is the definitive screen version of H.G. Well’s classic story of alien invaders—a Technicolor marvel of its day that won an Oscar for its visual effects and left an indelible mark on popular science fiction for the next four decades. Essentially the popcorn crowd’s alternative to the more cerebral and talky Day the Earth Stood Still, this adaptation of the 1898 novel effectively kicked off the “alien invaders” era of ’50s sci-fi, which would also give us the likes of Earth vs. the Flying Saucers. It’s actually legitimately scary at times, especially when the protagonists are confronted with the Martians themselves, outside the confines of their war machines. The gross design of the creature, with its tri-colored eyes and squat body, calls to mind a less pleasantly anthropomorphized version of Spielberg’s E.T., in the ickiest manner possible. Overachieving special effects wizardry make The War of the Worlds a must-watch for anyone with an interest in vintage practical effects. —JimVorel

73. Richard III (1955)

Laurence Olivier wrote, directed and starred in this adaptation of one of Shakespeare’s greatest historical plays, which also features John Gielgud, Ralph Richardson and Claire Bloom. While perhaps not the most brilliantly executed of Olivier’s Shakespeare adaptations (among other things, Olivier’s dominating presence is slightly distracting), it arguably did more to popularize and increase modern audiences for Shakespeare’s work because it was seen by so many. Richard might be Shakespeare’s nastiest villain, and Olivier definitely creates a monstrous monarch. There is a well-executed sense of courtly grandeur and the acting is superb across the board. One of the truly classic film adaptations of the Bard. —Amy Glynn

72. The Ladykillers (1955)

Watching The Ladykillers, one can’t help but notice the way it tends to play like a stage show, with its limited location, cast of archetypal criminal characters and “comedy of doors” mentality—it’s honestly surprising that it took 56 years for it to be adapted as a play in 2011. This is “dark comedy” indeed, as the gang of thieves led by Prof. Marcus (a ghoulish-looking Alec Guinness) take up roost in the home of a cantankerous old woman, Mrs. Wilberforce, posing as a string quartet while they pull off a major robbery. Of course, when the suspicious old bird catches wind of their scheme, her own life is thrown into the fray, and a startling, ever-mounting string of double and triple crosses begins to thin the ranks of the criminals. Veteran British actress Katie Johnson steals the show in her iconic turn as Mrs. Wilberforce, whose “cry wolf” stories have cast her in the role of local eccentric—it was one of the last roles that Johnson ever played before her passing less than two years later. The bickering between thieves recalls the heyday of Hollywood’s own screwball comedies, but the murderous undertones make one wonder if this might not have been the result if Alfred Hitchcock decided to make a crime comedy. —Jim Vorel

71. The Red Badge of Courage (1951)

In a rare example of a film surviving studio butchery with value and some auteurial vision intact, The Red Badge of Courage in its only viewable form—a studio-mandated 69-minute cut, with director John Huston’s own 95-minute version long thought lost—may be a sketch of the director’s original intent, but it’s still a substantial one. An adaptation of Stephen Crane’s Civil War novel, noted for its realism, Red Badge casts actual WWII hero Audie Murphy as Union trooper Henry Fleming, who flees from his first skirmish only to later seek redemption through recklessness on the battlefield. Huston’s noir-ish touches lend a despairing claustrophobia to an already despairing tale; Crane’s is a deeply unromantic war story, where proving one’s “courage” means shedding blood, and the natural instinct to fly from a slaughter is considered cowardice. Huston’s longer cut promised more fleshed-out portrayals of Henry’s platoon mates, but the film in its abbreviated form might actually be at an advantage: in keeping the other characters as ciphers, the movie heightens Henry’s isolation and makes an unintentional point about the soldiers in the bloodiest war fought on American soil being treated not as individuals, but pure, anonymous cannon fodder. —Brogan Morris

70. The Killing (1956)

Once upon a time, before Stanley Kubrick entered the pupal stages of his career and subsequently emerged as a god and master of his medium, he made movies like The Killing. Lean, mean and economical to a fault, The Killing gets lost in the shuffle of Kubrick’s career landmarks, but the man wielded impressive influence even in overlooked 80-minute heist flicks. (The Quentin Tarantino we all know and love and loathe might be a very different filmmaker today if not for The Killing.) Kubrick’s work here is no-frills and elegantly straightforward: Sterling Hayden plans one final holdup before retiring and settling down with Coleen Gray. No twists and turns, just good old-fashioned theft at the racetrack. The film revels in the gray morality of Hayden’s good intentions. Crime pays, at least until it doesn’t. —Andy Crump

69. Cinderella (1950)

Disney Studios was $4M in debt when they made this adaptation of the well-known fairy tale “Cendrillon” by Charles Perrault. I know, hard to believe, but they’d had a string of costly flops, including Fantasia and had lost their European market to the war. The film opened in 1950 to thunderous critical applause and put the studio well on its way back to being in the pink—by which I mean health, though it’s worth noting that this film is a direct ancestor of the Pink Sparkly Princess Syndrome that has become pandemic in three-to-seven-year-olds. While there might be no excuse for the merch-floods for which Disney is famous, this film is the real deal, one of the best animated features ever made. Disney pioneered the use of overdubbed vocals for the song “Sing, Sweet Nightingale,” creating the effect of the character singing harmony with herself. Salvador Dali and Christian Dior are said to have been direct influences on the clothes worn by the characters. The plot’s been with us for centuries, so I’ll forego the recap and say that the film takes full advantage of Disney’s fathomless imagination, mixing fantasy and humor and music in a way that captivates children more than sixty years later. And even though adults know “happily ever after” is a mixed bag at best, this film will probably still make you believe in it too. At least for a couple of hours. —Amy Glynn

68. Kiss Me Deadly (1955)

Completely at random, Mike Hammer (Ralph Meeker) nearly runs over a girl wearing nothing but a trenchcoat. While she’s soon caught by the police, Hammer’s intrigued by her tale and begins investigating her past. The very act of pursuing this sets a whole gang of mobsters, FBI agents and seemingly everyone else in the world against Hammer, all the while the girl’s identity and what secrets she was hiding become if anything less clear. That’s the world of Kiss Me Deadly, in which everyone, including Hammer, is a liar only looking out for themselves, yet the stakes are much higher than mere personal gain.

Few movies have ever been so perfectly of-their-time as Kiss Me Deadly. Anticipating the paranoid worlds of Thomas Pynchon and Don DeLillo a decade before they began publishing, it’s a perfect distillation of Cold War fear and dread molded into typical noir trappings. Of course, the search for a MacGuffin is nothing new to the genre, but here it’s given social context that transforms it from a plot device into an all-consuming philosophy. When given a new car, Hammer knows that it’s rigged to blow up in two different ways not because of any evidence but simply because that’s how the universe now works. “They” are always after him, and the “great what’s-it” he finally arrives at is every bit as apocalyptic as he thought it would be.

Emphasizing this is the intense stylization by director Robert Aldrich. Noirs are always known for their canted frames and chiaroscuro lighting, but here these stylistic elements are more than just conventions, they’re thematic commentary on the story. There’s always someone hiding in the shadows, and the odd angles characterize an essential inability to understand why things are happening. Disorientation, from the film’s trademark backwards title sequence to point of view shots that seem to come from no one, are Kiss Me Deadly’s norm.

Kiss Me Deadly was one of the last of the great true noir movies before Touch of Evil effectively destroyed the genre, but after Kiss Me Deadly there wasn’t much further for them to go. The noir had found its perfect topic in nuclear paranoia and had also become self-conscious, such that Kiss Me Deadly delivers its promised genre thrills while simultaneously acting as criticism of the direction hardboiled detective movies and books (particularly those by Mickey Spillane) had taken. There are certainly more accomplished movies in the genre, both the slicker Hollywood prestige noirs from a decade earlier and the artistically mesmerizing pictures Orson Welles was producing, but Kiss Me Deadly is the picture that took the style as far as it could go without jumping into self-parody. In the years since its release, Kiss Me Deadly has been copied so many times that many of its boldest elements are familiar, but they’ve done little to dull its overall impact.

67. The Thing From Another World (1951)

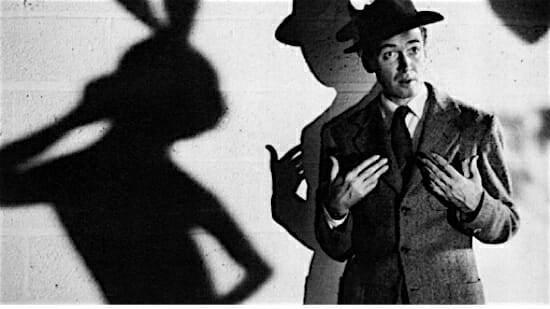

There’s some debate over how much of The Thing From Another World was directed by the credited Christian Nyby and how much came from the overseeing hand of Howard Hawks, but whoever directed it, they produced one of the best science fiction/horror crossovers of the 1950s. The characters aren’t so memorable as in John Carpenter’s 1982 remake, but the setting and sheer creepiness fill the gap. The moment when The Thing comes storming into the darkened barracks out of the arctic cold, backlit and looking like an indestructible goliath, is so seminal that even before he conceived of his remake, John Carpenter couldn’t help but putting it into a TV broadcast in Halloween by way of showing his fanboyism. There’s a definite strain of Cold War-era paranoia in the arctic air, a fear of the “other” as calculating alien and threat to all mankind. And then of course you have one of the most iconic closing monologues in sci-fi history: “Tell the world. Tell this to everybody, wherever they are. Watch the skies everywhere. Keep looking. Keep watching the skies!” —Jim Vorel

66. Harvey (1950)

Wealthy, affable drunk plus imaginary 6’4” bunny equals Pulitzer Prize, Broadway smash, and film adaptation starring the inimitable Jimmy Stewart as Elwood P. Dowd, whose drunken antics are not a problem for the locals until he starts claiming to see a pooka (a trickster spirit from Irish folklore). Suddenly, Elwood’s not so acceptable any more. Except Harvey, the imaginary rabbit, exerts an odd transformative effect on the other characters—with the exception of Elwood’s snobby sister Veta (Josephine Hull), who by the way is the only other person who can see Harvey. Veta tries to have Elwood committed to a mental hospital (his rabbit-antics are interfering with her plans to marry her daughter Myrtle (Victoria Horne) to A Good Match). Veta ends up getting herself committed instead, but the hospital director, Dr. Chumley, begins seeing Harvey as well (awkward…). A whimsical little fantasy/farce with a warm heart, Harvey is also a bit of a meditation of tolerance and the merits of “reality”; the drunken and possibly addled Elwood is significantly happier than the “normals” who surround him. It’s a lightweight film, but the sheer force of James Stewart’s charisma could make just about anything riveting. Even an invisible bunny. —Amy Glynn

65. Houseboat (1958)

In a lot of ways, Houseboat is a bit of a trivium, although it’s never unsatisfying to watch Cary Grant or Sophia Loren, like, ever. Grant plays a widowed father who takes his rather bratty and coddled children to live on a busted-up houseboat, ends up with Sophia Loren as his housekeeper and falls in love with her. It’s a star-vehicle romantic comedy with a kind heart and while it’s enjoyable generally, it won’t strike everyone as cinematic dynamite. There is really one standout feature to this film, but it’s significant because it was really unusual for its time. This film is very focused on the emotional world of the children and is surprisingly clear-eyed and perspicacious about the mixed emotions kids have when their parents repartner. Falling in love with Sophia Loren is easy. Winning back the hearts of your disaffected children? That’s serious. And Melville Shavelson takes it seriously in this film. It’s subject matter that does not always get much authentic consideration in films of this era and genre, and it is worth watching if for no other reason than to see Grant take it on with his typical panache. —Amy Glynn

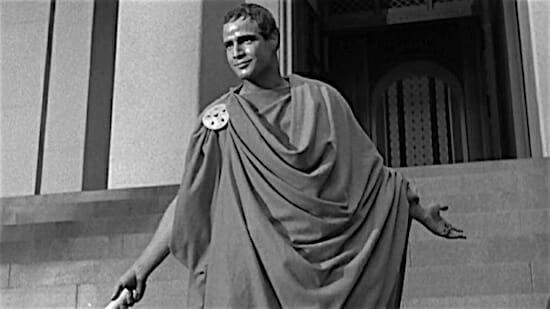

64. Julius Caesar (1953)

One of several renderings of classic Shakespeare plays made during the 1950s, this treatment of Julius Caesar is not cinematically groundbreaking; indeed it feels quite a lot as though you’re watching a film of a stage play. Which is okay. What matters here, folks, is the acting. The story is a well-worn classic, Shakespeare’s script has so thoroughly infiltrated the American lexicon that you’ve probably quoted it without even knowing you were doing it, and Mankiewicz’s directorial style is clean, concise and understated, giving as much space as possible to the actors. Caesar (Louis Calhern) is wonderfully imperious, but the standout performances are Sir John Gielgud as Brutus and the stunning Marlon Brando as Marc Antony. The acting is so spectacular that one wonders whether a more “imaginative” or “re-interpreted” directorial style might have obscured or obstructed it. Gielgud’s Brutus is intense and intelligent and melancholy; Brando’s Antony is passionate and fiery. This is quite simply a fantastic ensemble cast handling one of the great texts of Western literature. —Amy Glynn

63. Voyage to Italy (1954)

The third and final film in director Roberto Rossellini and actress Ingrid Bergman’s ravishing treatment of “this postwar tragedy” is also, after a fashion, the simplest: Scuttling the psychic extremes of Stromboli (1950) and Europe ’51 (1952), its portrait of a marriage suddenly exposed by the absence of more pressing conflicts is unmannered, naturalistic and distinctly modern, as if it were being imagined before our eyes. Though Katherine (Bergman) and Alex (George Sanders) travel to Italy to sell an inherited estate, the film’s gesture at a narrative seems almost moot when set against its emotional and aesthetic rigors; it is, at heart, a scintillating excavation of life avant le deluge, and of the impossibility of resuming it once the world has almost ended. By the time it makes the conceit explicit, as Katherine and Alex wander the ruins of Pompeii, Voyage to Italy emerges as perhaps the most delicate rendering of the war’s aftermath this side of Tokyo Story: “Life is so short,” Katherine says, crying, in the film’s closing sequence. “That’s why,” Alex responds, “one should make the most of it.” —Matt Brennan

62. Orphee (1950)

In the “totally brilliant but probably not to everyone’s taste” category is Jean Cocteau’s poetic and symbolism-heavy take on the myth of Orpheus. (Well, one of them; it was a trope to which he returned in two other films.) Jean Marais plays the title role in a retelling of the myth set in 1950s Paris, where a plot rife with love-and-death triangles unfolds in Cocteau’s otherworldly, beautiful-but-cryptic style. This film is clearly the work of a poet (the Orpheus myth has preoccupied poets for centuries but Cocteau’s directorial style is also poetic, allusive and pensively paced). Cocteau was also an opium addict, which definitely informs the dreamlike quality of the film and the preoccupation with slipping between the worlds of the living and the dead. Were you to call Orphee pretentious I’m not sure I’d bicker with you, but it is also a relic of a cinematic era that is simply gone, and it’s one of that era’s more beautiful and intriguing artifacts. Whether his style delights or annoys you, Cocteau was indisputably a genius, and this expressive, magical, rather haunting film probably approaches poetry as closely as the medium of film can. —Amy Glynn

61. Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1958)

It is a testament to the magical powers of Tennessee Williams that two cinematic retreads of this movie (one in the 1970s, one in the 1980s) appeared after Elizabeth Taylor and Paul Newman nailed it so thoroughly you’d have to be high to think you could top it. Then again, there was a certain amount of hubris in Richard Brooks deciding to handle the screenplay himself when he had Williams himself available. In a wealthy Southern family, Big Daddy (Burl Ives) is unaware he’s on the way out from cancer—but that fact isn’t lost on the rest of the family, who are hovering and drooling over his fortune. The operative word for this film: Hot. As in sweltering. As in oppressive, close, sticky-nasty hot. Williams’ story peels layer after icky layer off sexually frustrated Maggie (Taylor) and her tormented husband, Brick (Newman), revealing the baseness, mendacity and deceptiveness, or fragility and self-loathing that Williams seemed to find at the heart of a great many of his most enduring characters. Searing performances by Taylor and Newman, both at the height of their powers. —Amy Glynn

60. An American in Paris (1951)

The movies have paid homage to Paris, la Ville Lumière, for decades, from Gigi to Funny Face, Amélie to Midnight in Paris, but it’s An American in Paris that may honor the city better than all the rest: It’s bright, colorful, atmospheric, an utterly transporting experience, the kind of movie that makes such prime use of its setting that for just under two hours, you’d swear you were walking its streets on your own two feet. An American in Paris came out right in the middle of the musical boom in Hollywood between the late 1940s and the late 1960s, a time when musicals moved box office receipts and drew all kinds of critical praise to boot, but really, when we think of classic musicals, we tend to think of Gene Kelly, and when we think of Gene Kelly, we think of An American in Paris (unless we think of Singin’ in the Rain first). If you like your musicals chock full of whimsy and driven by tone, though, An American in Paris sings a far sweeter tune. —Andy Crump

59. I Vitelloni (1953)

If there’s any lesson worth learning from the history of Italian cinema, it’s that it’s generally unwise to bet against Federico Fellini. In most instances where producers or distributors cast a shadow of doubt on his films’ potential for success, the films in question perform performed so well that you’d swear they had minds of their own: It’s as if the movies, their value called into question, actively revolted against the qualms of Fellini’s superiors and hustled hard to make a buck at the box office. Take I Vitelloni. Fellini’s producer, Lorenzo Pegoraro, deflected the pleas of the distributor to shoot a new, upbeat ending that would utterly defeat the movie’s intentions not only as semi-autobiography but as a cohesive story. (Short version: The sudden discovery of an oil well in the film’s setting affords its characters instant wealth and happiness, leading to cheerful sing-song. Seriously.) Good thing he did, too. I Vitelloni was a hit, commercially and critically, so much so that it became the very first movie in Fellini’s body of work to receive distribution outside of Italy. Chalk that up to its universality. Whether you’re Italian, French, American, or any other nationality, you probably recognize a little of yourself in Fellini’s cast, their hopes, their dreams, their ambitions or lack thereof. —Andy Crump

58. The Big Sky (1952)

Saga Alert! Howard Hawks really was one of the great “go big or go home” auteurs of the mid-century, and while it seldom gets the accolades accorded to, say, Rio Bravo or The Big Sleep, if this Hawks film passed you by, I say go track it down and feast your eyes on the epic beauty of the Grand Tetons. A Western-ish drama set in the 1830s, it stars Kirk Douglas as Jim Deakins, a Kentucky frontiersman on a fur-trading trip up the Missouri. He and comrade Boone Caudill (Dewey Martin) find adventure and even some romance on their trip into the northwest frontier. There are comic inflections, in addition to Hawks’ signature attention to natural detail, and if the film runs a little long and maybe stays a bit light on the psychological depth side, this is still a beautifully shot meditation on the West. —Amy Glynn

57. Elevator to the Gallows (1955)

Prior to reinventing filmic language with their playful genre experiments, the members of France’s New Wave movement got their start as film critics. In fact, it was through their writings and discussions that the term “film noir” was first christened as a means of describing a certain breed of brooding postwar films. It’s not surprising then that Louis Malle—though not an official New Wave member—would settle on a film noir-influenced project as his first feature film. Acting both as an homage to noir as well as a subversion of its structure, Elevator to the Gallows stars Jeanne Moreau and Maurice Ronet as a pair of criminals whose plan to kill Moreau’s husband quickly falls apart when the Ronet character gets stuck in an elevator. This already absurd concept becomes all the more confounding when paired with the film’s unorthodox, experimental editing and somber, Miles Davis-performed jazz score. —Mark Rozeman

56. House of Wax (1953)

Here’s a trivia answer that never goes out of style: House of Wax was the first color 3D film from a major American studio, arriving only two days after the first black and white 3D movie, Man in the Dark. It’s also the film responsible for planting the idea of Vincent Price as a horror icon into the American subconscious—previous to this role, he had largely appeared in supporting parts, or in leading roles of dramas such as The Baron of Arizona. Here, though, Price finds his niche—a hammy, yet thespian quality that suggests he’s always in on the joke and enjoy enriching parts that wouldn’t have been at all memorable if they were coming from a lesser performer. He plays a talented wax sculptor who is maimed in a fire before setting off on a course of revenge against the world. Preying on young women in the area, he sets his sights on one in particular who is the spitting image of his destroyed masterwork, a sculpture of Marie Antoinette. The film has moments of effective creepiness that still resonate, as when Price is chasing the heroine down a foggy street at night, but much of the film is simply campy fun in the same vein as William Castle’s 1950s output—it’s no wonder he was drawn to Price for House on Haunted Hill and The Tingler. The moments meant to shamelessly showcase the 3D technology, such as the wandering paddle ball performer who bats his projectiles straight at the camera, are especially fun to chuckle at in 2017. —Jim Vorel

55. Rififi (1955)

Blacklisted and in exile, director Jules Dassin (American, despite the Gallic disguise his name could take on) made Rififi in Paris after more than a decade struggling under the House Un-American Activities Committee’s stranglehold over Hollywood. Reared in noir and similar wise-guy-inhabiting genres, Dassin seemed finally free with Rififi, a tightly wound testament to the weird and alluring dreamscape of criminal enterprise. In it, Jean Servais is a coughing, sagging pile of skin grafted to the frame of a formerly revered gangster, Tony “le Stéphanois,” a man who recently out of jail wants to play it safe until his pride gets the best of him. Assembling a team of European outlaws (including Dassin using the pseudonym “Perlo Vita” to portray Italian safecracker César), Tony masterminds the jewel heist to end all jewel heists, and, in turn, Dassin practically defined his own genre. The “heist film” is now a matter of cultural intuition—everything from Ocean’s 11 to Inception owes its intricacy and style to Dassin’s swagger—but in 1955, there was simply no other film like Rififi. Yet, even today, Dassin’s film is an astounding machine of filmmaking precision: In structure, dialogue, acting, cinematography and overall design, the film feels as if it’s working off of ineffable instincts, hiding nothing but implying everything. And working is perhaps the best way to describe what the film does best: Look only to the now-iconic, 33-minute heist sequence which serves as the film’s second act, totally without dialogue and careful to show, in bouts of unbelievable tension, just how much effort is required of putting together a seamless criminal act. It’s bravura filmmaking without one sweat-infused drop of ostentation, and rather than rest on melodrama to prove a point, Dassin sucks all romance out of the gangster equation, leaving the audience with nothing but the thankless toil of skirting the law. —Dom Sinacola

54. Stalag 17 (1953)

Tonally, Billy Wilder’s prisoners of war story is a true dramedy, fitting into an odd post-war space when American cinema-goers were apparently content to laugh at the horrors faced by prisoners, even while being reminded of the deadly results of incarceration, which were obviously even more dire for victims of the Holocaust. It’s William Holden who makes the film click and hum, portraying American airman Sefton as a somewhat sleazy but clever profiteer who figures that if he’s going to spend time in a POW camp, he might as well be an enterprising big shot while he’s there, living as comfortably as he can. In comparison with a film like The Great Escape, which would later come along and tell a story ringing with many of the same tropes, albeit without the screwball sense of humor, Stalag 17 is both an escape story and a light mystery, centered around the identity of the German informant who is sabotaging each attempt by the Americans to flee the camp and defy the Germans. With a cast of colorful characters and good-natured humor, Stalag 17 somehow takes a horrific premise and mines it for laughs more successfully than one would have thought possible. —Jim Vorel

53. Wild Strawberries (1957)

As befits a film about a physician, the most striking quality of Wild Strawberries is its surgical artistry. By the time of the movie’s release, Ingmar Bergman had seventeen directorial credits to his name, and his experience shows in each of Wild Strawberries’ 91 (or so) minutes. His craftsmanship is seamless, to the effect that one might offhandedly dismiss the nuance of the film as perhaps obtuse, or overly vague, or even ambiguous. But they’re either missing the point or they haven’t lived enough of a life to recognize Wild Strawberries’ reflective power. This is a movie of self-consideration, art that captures the experience of looking at oneself in the mirror and being dismayed at what they see: Maybe you’re not as curmudgeonly as Victor Sjöström’s Isak Borg, because how could you be, but everyone has endured their share of disappointments and felt bouts of unhappiness in degrees and fits and spurts throughout their own existences. Wild Strawberries is all about the reconciling with such past discontent and finding a form of peace in your present, regardless of the roads you’ve taken to get there. —Andy Crump

52. Ben-Hur (1959)

William Wyler’s adventure-drama broke Academy Awards records in 1959, with 11 wins. It’s also on the American Film Institute’s list of the 100 Best American films of all time. Those two facts alone probably put it in the mandatory viewing category before you get to Charlton Heston’s fabulous performance as Judah Ben-Hur, a Jew who tangles with the Roman Empire in the first century CE (concurrent with the time of Jesus of Nazareth). It’s a huge spectacle with a very iconic chariot race, and while contemporary viewers might feel more mixed about it than the Academy of the time did, it’s a spectacle by any standard (and worth watching for the chariot race alone). The story is a timeless one: Scrappy hero fights to remove the yoke of oppression, amid fierce violence and relentless cruelty. In the end, even if you find the acting a tad overdone, or the spectacle too spectacular, I think we might all be hardwired to relate to and love stories where scrappy heroes defeat oppressive institutions. It just grabs you. A perfect film? No. An important one? Yes. And did I mention the chariots? —Amy Glynn

51. La Strada (1954)

I like to imagine that if Fellini made La Strada today, we’d all be able to marvel at the depth of compassion he feels toward the film’s male lead, Anthony Quinn, playing the brutish traveling circus performer Zampano, a strong man who shatters chains with the might of his Herculean pecs. The reality is that asking your audience to pity an abusive, terrible human being at the near-literal last minute is asking a lot, but Fellini’s grace as an artist makes that pill easier to swallow. He heaps cruelties both physical and spiritual upon his two subjects, Zampano and the childlike Gelsomina (played by Fellini’s luminous and eminently talented wife, Giulietta Masina), reserving the brunt of the film’s suffering for her: Gelsomina labors under Zampano’s merciless direction and by consequence lives in a state of constant existential anxiety, ever pondering what her place is in the universal order. Maybe it’s just her lot in life to hurt. Maybe there is no universal order. Or maybe she was put on Earth to visit justice beyond the grace on Zampano as he collapses weeping on the beach, broken by the realization of his sins. La Strada is a deceptively simple picture layered with intricate, empathetic subtexts, and this, perhaps, is why it remains the most essential neorealist effort in Fellini’s body of work. —Andy Crump

50. Giant (1956)

This epic Western drama gave birth to the play (and its film adaptation) Come Back to the Five and Dime, Jimmy Dean, Jimmy Dean, and though the principal characters are played by Elizabeth Taylor and Rock Hudson (with a star studded supporting cast), it’s especially memorable as the last (and Oscar-nominated) performance of James Dean’s tragically short career-he died in a car accident while Giant was still in production. Giant is significant for its frankness in confronting racism and hierarchy as well as for stellar lead performances from Hudson and Taylor. As sprawling in scope and scale as the million acre ranch on which it takes place, Giant is surprisingly frank in its exploration of the racist underpinnings of American prosperity, and big on grandeur and sweeping visuals. This film might feel a bit bloated to contemporary viewers, and I wouldn’t argue with them, exactly—but Giant is an iconic, writ-large piece of filmmaking whose remarkable acting performances make it a must-see. —Amy Glynn

49. Paths of Glory (1957)

François Truffaut is notoriously and sort of erroneously credited as having said that, “There is no such thing as an anti-war movie.” He did say that he could not make a war movie about Algiers on the basis that, “to show something is to ennoble it.” He also said that “every film about war ends up being pro-war.” If this is true then maybe Paths of Glory is the closest the movies will ever get to producing an anti-war statement, though Stanley Kubrick’s trim World War I opus is better qualified as being disdainful of war: You can sense Kubrick’s contempt for his antagonists seething from behind the camera, his righteous indignation at the unapologetic cowardice of the craven old men who send others off to die on the field of battle at their behest. Maybe Paths of Glory isn’t anti-war, but it is pro-human, a film that celebrates true dignity and honor by recognizing that one need not rush forth to meet their inevitable death to be brave. —Andy Crump

48. Umberto D. (1952)

If ever you should find yourself in an unreasonably chipper mood, if ever the sun should shine upon each step you take as rainbows light your path, then let Vittorio De Sica’s Umberto D. be the cure to your cheer. Umberto D. is a king bummer, a real fucking downer, but it’s a downer out of necessity. Maybe you’re the type to refuse to make eye contact with homeless people, and if you are, then you’ll probably watch Umberto D with your gaze turned toward the wall, but that’s the point. De Sica means to make his audience confront the gross social inequities that force a retired government employee to consider stepping in front of a train clutching his adorable dog (because getting splattered all along the railroad tracks is preferable to slowly starving to death on Rome’s streets, apparently). No matter how wrenching the movie may be, you won’t be able to look away: Umberto D. is true, unflattering, and unfailingly compassionate, the perfect antidote for the obscuring comforts of middle class living. —Andy Crump

47. The Mummy (1959)

The classic Hammer Horror reboots of the ’50s are more or less all defined by their stylish flair and opulent color film settings, but The Mummy may be the most beautiful of them all, even more so than Horror of Dracula or Curse of Frankenstein. In terms of plot, it has little to nothing in common with the 1932 Universal original, instead seemingly drawing inspiration from (but vastly improving upon) the endless parade of slow, rather ugly Universal sequels. Christopher Lee once again has no lines here, but his presence is much more powerful and commanding than in Curse of Frankenstein—rather than an awkward, shambling corpse, the mummy Kharis feels more like an indestructible tank as he bursts through windows and shrugs off bullets like Jason Voorhees. Peter Cushing is back as his adversary once again, leading to another climactic fight to the death. The film backs off from the truly macabre ending of The Mummy’s Ghost that it’s parodying, but makes up for it with more of the grand, stately residences and Technicolor horrors you expect from the series. —Jim Vorel

46. To Catch a Thief (1955)

But really—he didn’t do it.

Cary Grant plays John Robie, a retired jewel thief who’s enjoying his golden years tending vines on the French Riviera. But just when the Grenache is hitting the perfect Brix level, a series of copycat heists put Robie back in the thiefly limelight. Seeking to clear things up, he compiles a list of locals who are known to have heistable jewels, and being a smart and wily guy, he starts tailing a very, very pretty one (Francie, played by Grace Kelly). Budding romance can be an accidental side-effect of these things, but when Francie’s ice does go missing, she suspects John and it sours their relationship, as one might expect. John goes on the proverbial lam to get to the bottom of it. Talk about jewels! Nothing ever sparkled quite like Cary Grant and Grace Kelly onscreen together, especially with the legendary Edith Head on costume design—and their peerless charisma is in amazing hands here. The film itself is a bauble, and unapologetically so. It’s light and frothy and absolutely not Rear Window, none of which is an indictment. Sometimes it’s enough for something to simply be charming and beautiful. This film proves it. —Amy Glynn

45. The Magician (1958)

If you have a buddy who isn’t into Ingmar Bergman, and really, don’t we all, then maybe point them to The Magician as an introduction to the Swedish master’s filmography: It’s a minor but great work, as expected from Bergman, from whom even minor efforts are as worthy as major ones from lesser filmmakers. Like most of his movies, The Magician sees him wondering aloud about life, death and existential matters. Unlike most of his movies, it’s a bit of a middle finger to his critics, or at least to skeptics, pedants, doubters and cynics, and a naked exploration of the innate deception of artistry. Then again, maybe don’t synopsize the film that way for your friend, of course, because if “Swedish arthouse filmmaking” doesn’t make The Magician sound unpalatably dry, then describing it as meta-storytelling will render it arid to their ears. But it shouldn’t! The Magician is as entertaining as it is poetic, sort of the cinematic equal of eating one’s vegetables when the vegetables have been sautéed in bacon fat. —Andy Crump

44. Mon Oncle (1958)

The films of Jacques Tati are films of methodical, meticulously staged bumbling blended with acute disdain for modernity in every imaginable manner: As an aesthetic, as an ideology, as a philosophy, as a signifier of changing times. Call Tati a nostalgist or call him a barmy old codger barking at the world from the safety of his porch, commanding all within earshot to get off of his damn lawn, but be sure to call him a comic genius while you’re at it, too. He deserves that much, doesn’t he? He did us all the favor of making the M. Hulot films, starting with Les Vacances de Monsieur Hulot in 1953, and continuing with Mon Oncle in 1958, Playtime in 1967, and Trafic in 1971. Of these, Mon Oncle feels most distressed—down in the dumps even—serving as a bridge between the sentimentality of Les Vacances de Monsieur Hulot and the undisguised social critique of Playtime, his greatest film. Mon Oncle is playful, jovial, good fun from start to close, a film built to show off Tati’s incredible gift for visual humor and also to serve as a melancholic send-off for the Belle Époque. He contrasts the beauty of old Paris with the austerity of new Paris, bereft of anything resembling character or style. We laugh fondly at Hulot’s graceless ineptitude, but we want to weep for the loss of those characteristics that make the city what it is, or what it was. —Andy Crump

43. Sansho the Bailiff (1954)

Two years before his death, and nearly 80 films into his career, Kenji Mizoguchi poured all of his empathetic intuition and finely tempered social critique into Sansho the Bailiff, a historical drama (or jidai-geki) about redemption not as a means to an end, but as the end itself. After their much-too-idealistic governor of a dad is forced into exile for disobeying a feudal lord—bureaucracy, always bureaucracy—siblings Zushio and Anju follow their mother, Tamaki (Kinuyo Tanaka), to years later visit the faraway land where their father ended up. On the way, a nefarious crone (and, it should be noted for symbolism’s sake, a priestess), tricks the trio into separating, after which Tamaki is sold into prostitution and the kids into the workforce of Sansho (Eitaro Shindo), an oafish but intimidating bailiff with a jonesin’ for branding the faces of disobedient slaves who attempt to escape their deplorable lots in life. As they grow up in the slave camp, the siblings take drastically different routes to adulthood: Anju (Kyoko Kagawa) remembers the magnanimity and mercy of their father, while Zushio (Yoshiaki Hanayagi) beefs out into one of Sansho’s favorite henchmen, often ready without blinking to do some branding on his master’s behalf. Only after Zushio is asked to do the unspeakable does he remember his humanity, agreeing to escape with his sister. From there, Sansho the Bailiff consolidates around Zushio as he attempts to transcend the broken order Sansho represents and come out the other end of the meat-grinder of a society with his dignity intact. While far from anything resembling overt hope, Sansho the Bailiff still operates as an optimistic tribute to the strength of the human spirit, especially after World War II: resilient, tolerant and, above all, the master of one’s fate. —Dom Sinacola

42. Ordet (1955)

The demands of Ordet (The Word) are small compared to the very real physical demands of the spiritual life director Carl Th. Dreyer explores within the film. Yet, these demands persist, in pace and piety, in the pathology of faith and the thankless indifference of the universe, making Dreyer’s 13th feature film a meticulously mannered slow-burn of metaphysical awakening confined within the stolid lives of those who can’t conceive of any reality otherwise. Amidst Dreyer’s characteristic long shots and the breathtaking cinematography of Henning Bendtsen (who transforms every one of Dreyer’s frames into a masterpiece of shadow and blocking), the Morten clan works through their typical days on the farm: baking, praying, tending to the field, forming scouting parties to track down Johannes (Preben Lerdorff Rye), the middle Morten son who read so much Kierkegaard he snapped, believing himself to be a squealy voiced Jesus Christ, often wandering away to preach the gospel to empty fields of wheat. Emptiness, in fact, is what Dreyer contemplates most, filling his bare rooms with silence and gesture and scripture—the tick of the clock signifies the anxious passing of life, while a woman’s low moans from another room haunt the film’s fringes. In this emptiness, Dreyer mixes the ordinary and the symbolic, earning every ounce of portent in which his aching film indulges and allowing the two seemingly disparate polls of the human condition to meet. By the time it occurs, the audience never questions whether the literal miracle at the heart of the film is justified, we simply understand that the most extraordinary moments in life come to those who never take the ordinary for granted. —Dom Sinacola

41. Sabrina (1954)

While boasted two of the most popular leading men of all time in Humphrey Bogart and William Holden, as well as the brilliant Billy Wilder (The Apartment, Some Like It Hot) as director and Ernest Lehman (Sweet Smell of Success, West Side Story) as one of its writers, it owes virtually every ounce of its justifiable status as a classic to the luminous Audrey Hepburn. I first saw Sabrina in my mid-30s but I already had had a crush on Audrey Hepburn for 20 years, since some friends and I rented the excellent late-career Hepburn-Sean Connery starrer Robin and Marian, thinking that James Bond as Robin Hood had to be fun. Imagine four teenaged boys bawling their eyes out at the end of that great but three-hanky weeper. But I digress … Hepburn was already a star, having won an Oscar for her breakout role in 1953’s Roman Holiday and here she shines once again. Often described as a romantic comedy, Sabrina has far more dramatic chops than giggles, and the 25-year-old Hepburn more than holds her own against heavyweights Holden and Bogart, taking the Cinderella archetype to new levels. If you can ignore the May-December aspect of the romantic pairings on offer, I dare you not to fall in love with this winning look at romance. The perfect example of the old axiom “sometimes what you want is right there in front of you.”

40. Strangers on a Train (1951)

Everyone has their favorite Hitchcock movie, and Hitchcock’s body of work has so much breadth and variation that no two cinephiles are likely to have the same favorite. Some people gravitate toward either The Birds or Psycho for their unmistakable iconography. Others might be inclined toward North by Northwest or The 39 Steps, or maybe Saboteur or Foreign Correspondent, Vertigo or Rebecca, as chief exemplars of the American thriller in its many forms. Me, I’ll take Strangers on a Train, one of Hitchcock’s minor efforts, any day of the week. By 1951, he’d been working in the movie biz for roughly thirty years and had to use two hands to count the number of hits he’d put out in between the new decade and the ’30s, and his nonchalant mastery over his medium shows in the film’s every frame. There’s nothing fantastical or outlandish about Strangers’ premise; it isn’t a movie driven by the imaginary but rather the imaginable, an immaculately crafted exercise in creeping dread where the antagonist is good old fashioned human immorality. That it handily evokes the political turmoil of its time without having mention the America’s Red Scare by name is remarkable, and the key to the film’s timelessness. It’s the perfect response to any oppressive political climate in any era. —Andy Crump

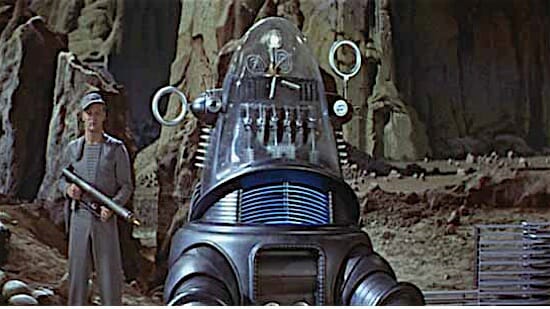

39. Forbidden Planet (1956)

Forbidden Planet is a rarity in a decade of low-budget B-movie sci-fi. Made by MGM Studios—and working as a narrative retread of Shakespeare’s The Tempest—this is high-quality, intelligent science fiction, featuring state of the art special effects. A ship of American astronauts lands on an alien planet where the inhabitants are trying to safeguard the ruins of a previous civilization. Famous for its iconic “Robby the Robot”—more complex and intelligent than most of its automated screen predecessors—Forbidden Planet stands head and shoulders above most science fiction of the ’50s. —Andy Crump

38. The Band Wagon (1953)