The 25 Best Thrillers on Amazon Prime

Out of any potential category of movie available to stream on Amazon Prime, thrillers may be the most elusive, mostly because it covers so much ground and Amazon has no real organizing function to delineate between, say, an action/adventure and what may “thrill” its audience.

So, for the (admittedly untenable) purpose of picking the best thrillers on Amazon Prime, we’ve mostly allowed the online retail giant to define what they consider a thriller, from neo-noir to sci-fi, from bleak action to blockbuster suspense. The thrillers Amazon Prime houses aren’t always for the squeamish—and aren’t always the easiest to find.

So here are the 25 best thrillers available to stream with Amazon Prime right now:

1. The Silence of the Lambs Year: 1991

Year: 1991

Director: Jonathan Demme

Stars: Jodie Foster, Anthony Hopkins, Scott Glenn, Ted Levine

Rating: R

Runtime: 118 minutes

The camera hugs her face, maybe trying to protect her though she needs no protection, and maybe just trying to see into her, to see what she sees, to understand why seeing what she sees is so important. Not even 30, Jodie Foster looks so much younger, surrounded in The Silence of the Lambs by men who tower over her, staring at her, flummoxed by her, perhaps wanting to protect her too, but more likely, more ironically, intimidated by a world that would allow such a fragile creature to wander the domain of monsters. As Clarice Starling, FBI agent-in-training, Foster is an innocent who’s seen more than any of us could ever imagine, a warrior who seems unsure of her prowess. That Jonathan Demme—a director who came up under the tutelage of Roger Corman, able to adopt then immediately shed genres at whim—corners Starling within the confines of a “Woman in Peril,” only to watch her shrug off every label thrown at her, is a testament to The Silence of the Lambs as feminist, not because it so thoroughly inhabits a female point of view, but because its violence and fear is the stuff of masculine toxicity. Demme’s film is only the second to adapt Thomas Harris’s Hannibal Lector novels to the screen, but it’s the first to draw undeniable lines between the way men see Clarice Starling and the way that serial killer Buffalo Bill (Ted Levine) projects his neuroses onto his victims. Demme (and Harris) links seeing to transformation to one’s need to consume, all pursued through a gendered lens, represented by the seemingly omniscient perspective of Hannibal Lector (Anthony Hopkins), a borderline asexual cannibal who literally eats those over whom he holds court. Buffalo Bill is a monster, and so is Lector, but the difference is that Lector does not attempt to possess Clarice Starling, though he sees her, because he is in control of that which he consumes. Buffalo Bill isn’t; as a man he believes that by consuming femininity he can become it, too stupid and too self-absorbed to realize that consumption is deletion, that wanting to protect a woman is only a matter of admitting that the World of Men is a weak and evil failure of the very ideals it strives to preserve. —Dom Sinacola

2. Robocop Year: 1987

Year: 1987

Director: Paul Verhoeven

Stars: Peter Weller, Nancy Allen, Miguel Ferrer, Ronny Cox, Kurtwood Smith

Rating: R

Runtime: 103 minutes

Throughout the late-’70s and indulgent 1980s, “industry” went pejorative and Corporate America bleached white all but the most functional of blue collars. Broadly speaking, of course: Manufacturing was booming, but the homegrown “Big Three” automobile companies in Detroit—facing astronomical gas prices via the growth of OPEC, as well as increasing foreign competition and the decentralization of their labor force—resorted to drastic cost-cutting measures, investing in automation (which of course put thousands of people out of work, closing a number of plants) and moving facilities to “low-wage” countries (further decimating all hope for a secure assembly line job in the area). The impact of such a massive tectonic shift in the very foundation of the auto industry pushed aftershocks felt, of course, throughout the Rust Belt and the Midwest—but for Detroit, whose essence seemed composed almost wholly of exhaust fumes, the change left the city in an ever-present state of decay. And so, though it was filmed in Pittsburgh and around Texas, Detroit is the only logical city for a Robocop to inhabit. A practically peerless, putrid, brash concoction of social consciousness, ultra-violence and existential curiosity, Paul Verhoeven’s first Hollywood feature made its tenor clear: A new industrial revolution must take place not within the ranks of the unions or inside board rooms, but within the self. By 1987, much of the city was already in complete disarray, the closing of Michigan Central Station—and the admission that Detroit was no longer a vital hub of commerce—barely a year away, but its role as poster child for the Downfall of Western Civilization had yet to gain any real traction. Verhoeven screamed this notion alive. He made Detroit’s decay tactile, visceral and immeasurably loud, limning it in ideas about the limits of human identity and the hilarity of consumer culture. As Verhoeven passed a Christ-like cyborg—a true melding of man and savior—through the crumbling post-apocalyptic fringes of a part of the world that once held so much prosperity and hope, he wasn’t pointing to the hellscape of future Detroit as the battlefield over which the working class will fight against the greedy 1%, but instead to the robot cop, to Murphy (Peter Weller), as the battlefield unto himself. How can any of us save a place like Detroit? In Robocop, it’s a deeply personal matter. —Dom Sinacola

3. Mission: Impossible – Ghost Protocol Year: 2011

Year: 2011

Director: Brad Bird

Stars: Tom Cruise, Jeremy Renner, Simon Pegg, Paula Patton

Rating: PG-13

Runtime: 132 minutes

While Christopher McQuarrie continues to codify Tom Cruise as the asexual ubermensch of our action franchise dreams, it took an animator to realize what wonders could be unleashed when directing the superstar like one would a cartoon character. Tom Cruise can do things normal people can’t, maybe because normal people won’t, though Tom Cruise might just say that normal people don’t, the man’s career providing ample evidence that he believes he can do things normal people can’t because he does them. His impossible mission is himself; Brad Bird understood this. The fourth Mission: Impossible movie, then, is a testament to Tom Cruise’s logic, to having him do astounding things because he’s doing them, for us, to both show us what we could do if only we were doing it, and to entertain us, because he’s nothing if not a consummately entertaining performer. When Ethan Hunt (Cruise) clambers over the exterior of the Burj Khalifa, Bird captures Cruise with the open-faced awe of a director who can’t believe the malleable specimen he’s got in his grasp. When the Kremlin implodes with more than a hint of disaster porn footage, or when Ethan Hunt’s outrunning an all-consuming sandstorm, or when Ethan Hunt’s escaping from a maximum security prison in Moscow, Bird’s imagination spews from every spectacle, America’s favorite ridiculous leading man at the heart of it all, looking chiseled and genial but also like he doesn’t understand human touch. This is Cruise’s gift to Bird, and this is Bird’s gift to us, paying it forward. —Dom Sinacola

4. You Were Never Really Here Year: 2018

Year: 2018

Director: Lynne Ramsay

Stars: Joaquin Phoenix, Ekaterina Samsonov, John Doman, Judith Roberts, Alex Manette, Alessandro Nivola

Rating: R

Lynne Ramsay has a reputation for being uncompromising. In industry patois, that means she has a reputation for being “difficult.” Frankly, the word that best describes her is “unrelenting.” Filmmakers as in charge of their aesthetic as Ramsay are rare. Rarer still are filmmakers who wield so much control without leaving a trace of ego on the screen. If you’ve seen any of the three films she made between 1999 and 2011 (Ratcatcher, Morvern Callar, We Need to Talk About Kevin), then you’ve seen her dogged loyalty to her vision in action, whether that vision is haunting, horrific or just plain bizarre. She’s as forceful as she is delicate. Her fourth film, You Were Never Really Here—haunting, horrific and bizarre all at once—is arguably her masterpiece, a film that treads the line delineating violence from tenderness in her body of work. Calling it a revenge movie doesn’t do it justice. It’s more like a sustained scream. You Were Never Really Here’s title is constructed of layers, the first outlining the composure of her protagonist, Joe (Joaquin Phoenix, acting behind a beard that’d make the Robertson clan jealous), a military veteran and former federal agent as blistering in his savagery as in his self-regard. Joe lives his life flitting between past and present, hallucination and reality. Even when he physically occupies a space, he’s confined in his head, reliving horrors encountered in combat, in the field and in his childhood on a non-stop, simultaneous loop. Each of her previous movies captures human collapse in slow motion. You Were Never Really Here is a breakdown shot in hyperdrive, lean, economic, utterly ruthless and made with fiery craftsmanship. Let this be the language we use to characterize her reputation as one of the best filmmakers working today. —Andy Crump

5. Fight Club Year: 1999

Year: 1999

Director: David Fincher

Stars: Brad Pitt, Edward Norton, Helena Bonham Carter, Meat Loaf

Rating: R

Runtime: 139 minutes

Based on the mind-bending novel by Chuck Palahniuk, the film version of Fight Club improves on its source. Thank you, David Fincher. Both Brad Pitt and Edward Norton can chalk their performances up as “best role” material. It’s a gritty thriller that features violence as a tool to cope with life’s mundanity, and the dangers that accompany that line of thinking. Most people who didn’t read the book were probably just as surprised about the ending as they were when Meat Loaf popped up in the film. Fight Club is one of the best movies of the ‘90s. Period. If you have a problem with that, then maybe we should step outside. —Shawn Christ

6. No Time To Die Year: 2021

Year: 2021

Director:Cary Joji Fukunaga

Stars: Daniel Craig, Lea Seydoux, Rami Malek, Ben Whishaw, Lashana Lynch, Naomie Harris, Ralph Fiennes, Jeffrey Wright, Ana de Armas, Christoph Waltz

Rating: PG-13

It’s telling that Craig’s swan song No Time to Die being the longest Bond ever, at a superhero-sized 163 minutes, probably won’t inspire as much public self-flagellation as the leaner, meaner Quantum. No Time to Die is neither lean nor mean; it’s a hard-working attempt to reconcile the Bond rituals with a series-finale emotional weight that these movies have been accumulating (with mixed success) since 2006. Apparently, that reconciliation process takes time: Director Cary Joji Fukunaga (or, more likely, Eon Productions, the tight-gripped caretakers of the Bond franchise) is so unwilling to drop either aspect of this opus that it often feels like two movies in one, both feature-length. So pronounced is the movie’s two-track approach that many of its story elements feel doubled: The opening sequence is a bit of creepy, horror-tinged backstory for Lea Seydoux’s Madeleine Swann (first introduced in the half-lackluster Spectre) and a big Bond action sequence jostling him out of retirement. It feels like 30 minutes before the opening titles finally roll. Then, after those credits, it’s five years later, and the movie gives us a whole other Bond retirement, this time in Jamaica rather than Italy. If it seems like the characters, locations and plot turns keep on coming, and that it’s impossible to keep from mentioning the other Craig Bonds that have preceded it, that’s very much the experience of watching No Time to Die—and not always unpleasantly. If you can accept a saga-fication of Bond, with callbacks and plot threads and interconnections, it’s, at minimum, less of a Forever Franchise than the endlessly self-teasing superhero mythologies (ironic, given that this is the most forever of franchises). This movie really does want to tie the extended Craig era—longest in years, though not in total output—together. Despite the craft on display, No Time to Die lacks pantheon-level Bond action sequences. Cuba is terrific fun, Fukunaga stages a solid late-movie one-take stairwell fight and the big/delayed opener delivers. But the movie is more concerned with the human stuff, a decision that’s by turns hubristic, heartening and unprecedented. (Well, not entirely. On Her Majesty’s Secret Service tried something different, and the filmmakers show their belated appreciation for that once-maligned Bond classic here.) The emotional weight it’s trying to foist onto its loyal audience doesn’t always feel earned, just because it’s tricky to parse what, if anything, the movie is actually trying to say about a James Bond who has spent the majority of five movies beginning and ending, sometimes on a loop. Yet fans may welcome the chance to watch the series struggle against its conventions: Are these performances good, for example, or are all the good guys just beautiful? Is this movie visually sumptuous or was it just shot on film? Has James Bond been deepened, or just weathered? As neatly as No Time to Die wraps up, its certainty is ultimately limited to the last line of the credits: James Bond Will Return. How is another question altogether.—Jesse Hassenger

7. Detour Year: 1945

Year: 1945

Director: Edgar G. Ulmer

Stars: Tom Neal, Ann Savage, Claudia Drake, Edmund MacDonald

A Poverty Row staple with an unknown cast peering into the post-war dark night of the soul, Detour has come to embody the best film noir has to offer—namely, that budget and schedule concerns indirectly enriched the artistic product, paring down a weightier script and even more bloated source novel into a precise, exquisitely sharp bit of storytelling economy. Trapped within the sweaty mind of always-broke jazz pianist Al Roberts (Tom Neal) as he heads West from New York to settle down with his girlfriend (Claudia Drake), a symbol of stable life for Roberts who absconded with his heart to try to “make it” in Hollywood, we’re stuck with only the unlucky guy’s version of events throughout his increasingly desperate trip. After all, his hitchhiking journey seems doomed to fail from the start, but it grows damn near bleak with the accidental cadaver-ing of a gregarious Charles Haskell (Edmund MacDonald) following a whirlwind buddy meet-cute, and then completely hopeless with the introduction of Vera (Ann Savage), an iconic femme fatale who doesn’t have to try hard to ensnare Roberts, by that point so far out of his league he’s got his pants pulled up well past his nipples. As much an efficient encapsulation of its genre as it is a noir drowning entirely within its own hell-bent nightmare, Detour is most impressive for how gracefully Ulmer can get the most out of so little. —Dom Sinacola

8. The Vast of Night Year: 2019

Year: 2019

Director: Andrew Patterson

Starring: Sierra McCormick, Jake Horowitz

Rating: PG-13

The Vast of Night is the kind of sci-fi film that seeps into your deep memory and feels like something you heard on the news, observed in a dream, or were told in a bar. Director Andrew Patterson’s small-town hymn to analog and aliens is built from long, talky takes and quick-cut sequences of manipulating technology. Effectively a ‘50s two-hander between audio enthusiasts (Sierra McCormick and Jake Horowitz playing a switchboard operator and disc jockey, respectively) the film is a quilted fable of story layers, anecdotes and conversations stacking and interweaving warmth before yanking off the covers. The effectiveness of the dusty locale and its inhabitants, forged from a high school basketball game and one-sided phone conversations (the latter of which are perfect examples of McCormick’s confident performance and writers James Montague and Craig W. Sanger’s sharp script), only makes its inevitable UFO-in-the-desert destination even better. Comfort and friendship drop in with an easy swagger and a torrent of words, which makes the sensory silence (quieting down to focus on a frequency or dropping out the visuals to focus on a single, mysterious radio caller) almost holy. It’s mythology at its finest, an origin story that makes extraterrestrial obsession seem as natural and as part of our curious lives as its many social snapshots. The beautiful ode to all things that go [UNINTELLIGIBLE BUZZING] in the night is an indie inspiration to future Fox Mulders everywhere. —Jacob Oller

9. The Invisible Man Year: 2020

Year: 2020

Director: Leigh Whannell

Stars: Elisabeth Moss, Oliver Jackson-Cohen, Harriet Dyer, Aldis Hodge, Storm Reid, Michael Dorman

Rating: R

Aided by elemental forces, her exquisitely wealthy boyfriend’s Silicon Valley house blanketed by the deafening crash of ocean waves, Cecilia (Elisabeth Moss) softly pads her way out of bed, through the high-tech laboratory, escaping over the wall of his compound and into the car of her sister (Harriet Dyer). We wonder: Why would she run like this if she weren’t abused? Why would she have a secret compartment in their closet where she can stow an away bag? Then Cecilia’s boyfriend appears next to the car and punches in its window. His name is Adrian Griffin (Oliver Jackson-Cohen), and according to Cecilia, Adrian made a fortune as a leading figure in “optics” (OPTICS!) meeting the self-described “suburban girl” at a party a few years before. Never one to be subtle with his themes, Leigh Whannell has his villain be a genius in the technology of “seeing,” in how we see, to update James Whale’s 1933 Universal Monster film—and H.G. Wells’ story—to embrace digital technology as our primary mode of modern sight. Surveillance cameras limn every inch of Adrian’s home; later he’ll use a simple email to ruin Cecilia’s relationship with her sister. He has the money and resources to peer into any corner of Cecilia’s life. His gaze is unbroken. Cecilia knows that Adrian will always find her, and The Invisible Man is rife with the abject terror of such vulnerability. Whannell and cinematographer Stefan Duscio have a knack for letting their frames linger with space, drawing our attention to where we, and Cecilia, know an unseen danger lurks. Of course, we’re always betrayed: Corners of rooms and silhouette-less doorways aren’t empty, aren’t negative, but pregnant with assumption—until they aren’t, the invisible man never precisely where we expect him to be. We begin to doubt ourselves; we’re punished by tension, and we feel like we deserve it. It’s all pretty marvelous stuff, as much a well-oiled genre machine as it is yet another showcase for Elisabeth Moss’s herculean prowess. —Dom Sinacola

10. Face/Off Year: 1997

Year: 1997

Director: John Woo

Stars: Nicolas Cage, John Travolta

One of the best action bonanzas of the ’90s begins with the murder of a small boy, and the following 130 brilliant, dove-dunked, borderline lysergic minutes do nothing to denounce the glorious shamelessness of those very first moments. Contrary to contemporary narratives, Nicolas Cage has always been a bit much, but as swaggering sociopath Castor Troy (and then as traumatized lawman Sean Archer), the Oscar-winning actor seems to realize that everything has been building to this Face/Off, that perhaps he had been put on this earth for the sake of this film, and that director John Woo—already an action maestro by this point with The Killer, Hardboiled and Hard Target—should be his Metatron, recording and overseeing this important time in the Realm of Humans. Similarly, John Travolta leans just as hard into his half of the two-hander, saddled with the added pressure of playing a bad guy who’s playing a dad who lasciviously stares at “his” own teenage daughter, encouraging her to smoke by basically flirting with her, and like most Travolta performances from the past 20 years, fails spectacularly to not make it weird. With a plot (FBI agent undergoes experimental face surgery to pretend to be super criminal in order to trick super criminal’s less-super criminal brother into revealing the location of a bomb) that makes way less sense as a Wikipedia synopsis than it does on-screen, Face/Off should be a disaster. And hoo boy is it ever—plus a landmark in action filmmaking.—Dom Sinacola

11. AmbulanceRelease Date: April 8, 2022

Director: Michael Bay

Stars: Yahya Abdul-Mateen II, Eiza González, Jake Gyllenhaal, Garret Dillahunt, Keir O’Donnell, Olivia Stambouliah, Jackson White, A Martinez, Cedric Sanders

Rating: R

If Ambulance, Michael Bay’s 15th feature currently basking in a gleeful critical reappraisal of Bay’s canon, feels as entelechial as Bad Boys II, it can only be because Bay has found himself in the absolute best time to be Bay. Though an ensemble of Angelenos fills out the film as it barrels to pretty much the only conclusion it could have, Ambulance is about as tidy as a Michael Bay film can get. Within ten minutes we’re deep in Ambulance: Strapped for money to pay his wife’s escalating medical bills, let alone care for their infant son, Will Sharp (Yahya Abdul-Mateen II) agrees to join his adoptive brother Danny (Jake Gyllenhaal, always a joy to behold) on one last big score, a bank heist that goes inevitably wrong. Subsequently, they shoot a cop (Jackson White) and commandeer the cop’s ambulance, also occupied by the “best” EMT in L.A., Cam Thompson (Eiza González)—just one more embittered soul in the grand gray tapestry that is the City of Angels. As Danny loses control and Will more and more accepts his fate as the offspring of a fabled bank-robbing psychopath, their bank robber father spoken of in hushed tones and unbelievable stories, the entire militarized might of the LAPD descends upon the stolen ambulance, led by Captain Monroe (Garret Dillahunt), a man who festishizes the police enough that Bay doesn’t have to. Even when FBI Agent Clark (Keir O’Donnell) gets involved, he’s only invited into Monroe’s inner circle because he went to college with Danny. Bad Boys and the fever dream of Bad Boys II are about how Michael Bay thinks that cops must be psychopaths in order to confront a modern psychopathic world. In Ambulance, as much as his vision of the LAPD comprises sophisticated surveillance and world-killing artillery to rival the most elite military power of the U.S. government—making sure it all looks really fucking cool—he also makes sure to interrupt an especially destructive chase sequence (as he once had Martin Lawrence declare the events happening on screen obligatory and nothing else) among so many especially destructive chase sequences, to have Monroe’s left hand, Lieutenant Dhazghig (Olivia Stambouliah), tell him how many tax dollars they’re annihilating. Later, many, many police officers die in explosions and hails of gunfire, bodies indiscriminately everywhere. One detects glee in these scenes, as if Bay’s countering Monroe’s dismissal of so many flagrantly abused tax dollars by blowing up half the LAPD in a spectacle that practically demands applause. Maybe Michael Bay no longer sees the utility in unleashing psychopathic cops on a psychopathic world, but maybe he never did. In Bay’s L.A., there are no sides, no good guys and bad guys, just a person who “saves my life” or doesn’t—just people with holes punched into their bodies and people without. This is Bay’s distinction between the “haves” and “have nots”: People who have mortal trauma and people who don’t. The film’s disposable blue collar Italian lump, Randazzo (Randazzo Marc), puts it simply: “L.A. drivers! They’re all mamalukes.” Behold this urban wasteland of struggling mamalukes—it teems with more style than we’ll ever deserve.—Dom Sinacola

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Year: 2012

Year: 2012 Year: 2012

Year: 2012 Year: 1989

Year: 1989 Year: 2000

Year: 2000 Year: 2016

Year: 2016 Year: 2016

Year: 2016 Year: 2011

Year: 2011 Year: 2018

Year: 2018 Year: 2002

Year: 2002 Year: 1995

Year: 1995 Year: 1963

Year: 1963 Year: 2020

Year: 2020 Year: 2020

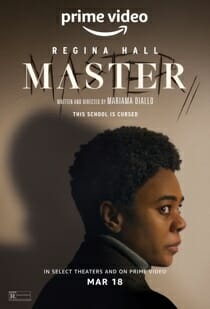

Year: 2020 Amazon Prime Release Date: March 18, 2022

Amazon Prime Release Date: March 18, 2022