Val Paints a Fascinating, Frustrating Self-Portrait of Artistic Reinvention

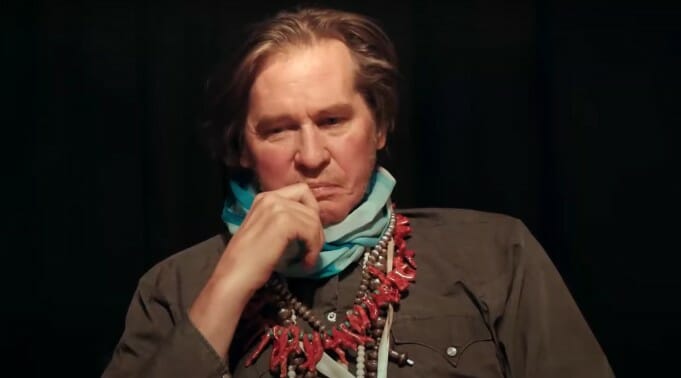

Despite knowing that actor Val Kilmer underwent two tracheostomies after being diagnosed with and beating throat cancer in the late 2010s, the voice box mechanism now implanted in his neck altering his voice to a raspy garble, one might think the actor was somehow effortlessly narrating his own documentary. But Kilmer wasn’t suddenly blessed with breakthrough technology to render his voice recognizable once more, nor was Val equipped with the same highly controversial AI tech as that of Roadrunner. No, Kilmer’s 26-year-old son, Jack, sounds eerily like his father once did. And though Kilmer’s difficult-to-parse robotic croak still proliferates Leo Scott and Ting Poo’s documentary (he admits he sounds much worse than he feels), it’s Jack’s voice which acts as the guiding narration throughout—a living, breathing bridge between his father’s past, present and even future; a reminder of what once was and what will never be, and what possibilities still exist in spite of both.

Less a documentary, Val is a subjective self-portrait of a prolific actor, and a revealing, often frustrating look at the way he views himself and his life’s work. Though directed and edited by Scott and Poo (joined by Tyler Pharo in the edit), it’s hard to view Val as anything but wholly representative of and handled by the subject himself. Kilmer as star, producer, writer and cinematographer. Along with his son’s narration and the handwritten notes Kilmer etches onto shots, the documentary is almost entirely stitched together by footage that Kilmer’s been amassing since he was a boy growing up in the Chatsworth neighborhood of Los Angeles. Kilmer has two brothers, Mark and Wesley, while his father, Eugene, was an industrialist and real estate developer. His mother, Gladys, was a spiritualist and immensely influential on Kilmer’s lifelong faith in Christian Science—a topic close to Kilmer’s heart and only one of which is interestingly glossed over here.

From a young age, Kilmer had a passion for acting and for being both in front of and behind the camera, relaying that he was actually the first person he knew to own a video camera at all. A natural clown and gifted performer, Kilmer revelled as much in an audience’s attention as he did in stepping away from the spotlight and allowing himself to be the spectator. Kilmer’s archival footage—home movies, including short films with his brothers and school plays; behind-the-scenes looks at major films; audition tapes; film ideas—reveal an endlessly curious artist transfixed by the space that he occupies. Kilmer’s dedication to documenting his life is less emblematic of egomania than of the pure desire to record as much of his placement within the world as he can, and of the other people and artists whom he is privileged to experience gravitating towards his orbit.

Shortly after becoming, at the time, the youngest person to ever be accepted into The Juilliard School’s Drama Division, Kilmer experienced a major loss: Wesley passed away unexpectedly at 15. Though grief placed a moratorium on Kilmer’s home videos and short family films, his undaunted commitment to his craft eventually landed him his first major role in 1983: A lead in the off-Broadway play The Slab Boys. Yet, even after being bumped to third lead following the inclusion of fresh-faced yet bigger-name actors Kevin Bacon and Sean Penn—whom Kilmer films cheekily mooning the camera in their dressing room—Kilmer doesn’t allow the double demotion to damage confidence in his undeniable talent.

A year later, a starring role in the Zucker Brothers parody Top Secret! paved the way for his recognition as a major Hollywood star. The ensuing years saw him in big mainstream films like Top Gun, Willow, Heat and The Doors—the latter of which he nabbed by sending an audition tape to director Oliver Stone, an uncommon practice at the time that’s illustrative of Kilmer’s desire to work in exciting auteur projects. Kilmer was always looking for, if not the next best thing, the next beautiful thing. This is made ironic, however, by his decision to turn down Robert Altman twice, and pass on a role in David Lynch’s Blue Velvet. Still, such convictions are most likely why Val chooses to almost entirely skip over his work from the 2000s and the 2010s, years undeniably marred by less prestigious fare, but which still include some genuinely fantastic performances.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-