An Ear for Film: EFF-U

The three best movie-related podcast episodes of the week.

Each week, Dom plumbs the depths of podcast nation to bring you the best in cinema-related chats and programs. If writing about music is like dancing about architecture, then writing about movie podcasts is like listening to someone describe someone dancing about architecture.

Have a suggestion for a good movie podcast? Slide into Dom’s DMs on Twitter.

In my last column, I teased the emergence of my own Ear for Film Universe (the EFF-U) as a personal corollary to the many cinematic universes becoming the norm for any major film studio lately, and the more I think about it the more obvious it becomes a very real possibility. Either that, or so-called “cinephiles” and film-world cognoscenti and the like are all keyed into some sort of Jungian mental vein when it comes to what’s worth yammering on about, and so all talk about all the same stuff.

For example: This week on The Canon, Devin and Amy debate the merits of John Singleton’s Boyz n the Hood, making for one more excellent episode fueled by the two hosts’ complete disagreement over whether or not the movie is actually any good. Devin thinks it’s an ineptly made piece of garbage, while Amy finds its energy—its necessity to tell its story—endearing, inspiring even. I haven’t seen the film in over a decade, so I won’t weigh in on where I fall (though Devin’s arguments seem more concrete, especially when Amy’s unable to respond to any of his criticisms with anything other than the aforementioned burning “urge” to tell a yet untold American story), but Amy, in the throes of near malicious frustration, brings up Dope, a movie she really likes and one Devin hates.

Devin rehashes his reasons for why he dislikes Dope so much, an argument which, I realized, echoed the sentiments made by Wesley Morris on Sam Fragoso’s Talk Easy podcast a few weeks ago—that is, until Devin cites Morris’s initial review. Amy’s conceit, too, that their divide over Boyz n the Hood mirrors their extreme discord regarding Dope: That dynamic itself mirrors the dissent I mentioned last week in alluding to how much the guys of Black Men Can’t Jump (In Hollywood) admire Dope, almost for the exact same reasons (nostalgia, the representation of Black America for white audiences, etc.) that Morris hates Dope so much. The things that Amy loves about Boyz n the Hood are the things Devin can’t stand, so either every film-related podcast I listen to is tangled inextricably in a web of zeitgeist-friendly opinions and conversations, or having an opinion about film is just, and only, a matter of subjectivity.

Instead: EFF-U. It’s what I believe in.

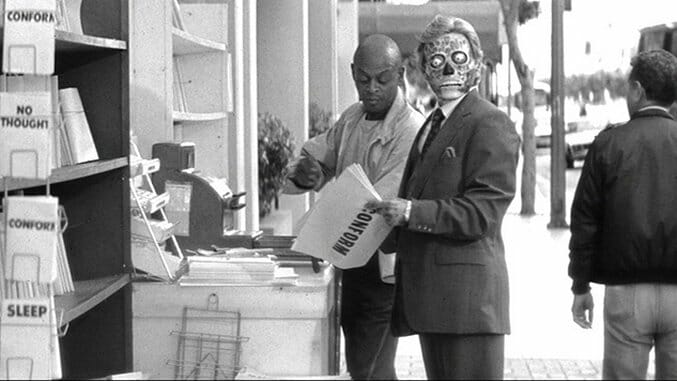

This week, due to no finagling whatsoever on my part, a thick through line draws each of my picks together in ways that can only possibly be preordained. Here’s another example: After listening to Bret Easton Ellis’s interview with John Carpenter (discussed below), I checked out the new Blumhouse-based horror podcast, Shock Waves, to hear them talk about the interview because, coincidentally, John Carpenter just made an agreement with Blumhouse to serve as a consultant on the company’s new acquiring of the rights to the Halloween franchise. It was a listening experience followed soon after by I Was There Too’s interview with Peter Jason, who played Gilbert in They Live, which was directed by John Carpenter.

It’s like I’m Jim Carrey in The Number 23 over here.

So make sure to look for connections in all things, no matter how adversely it affects your home life, and then check out my picks for the three best movie-related podcasts of the week:

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

How Did This Get Made?

How Did This Get Made? I Was There Too

I Was There Too Bret Easton Ellis Podcast

Bret Easton Ellis Podcast