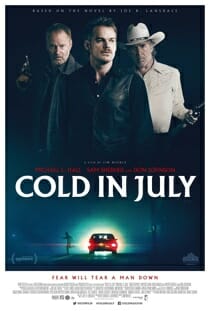

Cold in July

Richard Dane seems like a decent-enough man. Living in East Texas in 1989, he has a wife and child, and when he hears a noise coming from the living room late one night, he goes out cautiously, holding his dead father’s gun tentatively. He didn’t mean to kill anyone. And he certainly didn’t intend to have just about everything in his world change in the moment when he accidentally pulled the trigger.

Cold in July tells the story of Richard, a small-town guy who runs a framing store, and because the film is directed by Jim Mickle (Stake Land, the American remake of the cannibal thriller We Are What We Are), there’s an anticipation that our hero’s journey will be fraught with slithering, queasy peril. Our presumption turns out to be correct, but for the film’s first half, Mickle teases us with the possibility that Cold in July will be more than a well-executed genre flick. That it eventually settles into that terrain in its second half can’t help but feel slightly disappointing. The movie succeeds on its own terms, but a more intriguing story is within its reach.

Michael C. Hall plays Richard, not overdoing the character’s regular-hick modesty. Richard may not be a particularly sharp fellow, but he’s no dummy, either. More accurately, he seems like the sort of man who blends in, all the better not to attract attention. Which is why he’s even more upset when he shoots a home-invader, a bandana obscuring the burglar’s face. In the aftermath, Richard finds himself a local celebrity because of his decisive action (which only happened because he panicked), but it also attracts the attention of the criminal’s father, Ben (Sam Shepard), who’s recently gotten out of prison and never knew the son he had to leave behind at an early age. Fearing that Ben will take vengeance on his family, the mild-mannered Richard must be on high alert—but when he realizes that the burglar he killed wasn’t Ben’s son, despite the assurances of the police, he realizes that Ben may turn out to be an unlikely ally in solving this mystery.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-