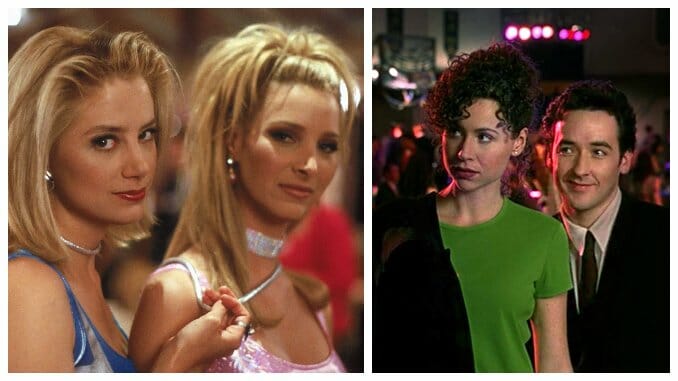

Disney’s Reunions at 25: Grosse Pointe Blank and Romy and Michele’s High School Reunion

With commencement season just around the corner, let’s take a moment to honor the 25th anniversary of the 10-year reunion of the class of 1986, or 1987, or anyway, sometime in the late ’80s. It may not seem like a particularly auspicious (or specific) milestone, but that nebulous graduating class was special enough to be honored with two different mainstream comedies, released a mere two weeks apart—by two different subsidiaries of the same studio, no less! Somehow, Disney’s Hollywood Pictures put out Grosse Pointe Blank, about a neurotic hitman attending his 10-year reunion, on April 11, 1997, and Disney’s Touchstone Pictures followed it with Romy and Michele’s High School Reunion, about two best friends doing the same, two weeks later on April 25. They grossed nearly identical sums in North America, suggesting a very specific (if surprisingly robust, in the scheme of things) audience for movies about Generation Xers grappling with the psychological wounds of high school and decaying vestiges of their late-‘80s youth.

Romy and Michele’s High School Reunion engages more directly with keeping the look and attitudes of ’80s culture alive. Despite Romy (Mira Sorvino) and Michele (Lisa Kudrow) hailing from the Tucson area, they both have a valley-girl affect that fits with their adopted Los Angeles home. (That’s especially true of Sorvino, who won her Mighty Aphrodite Oscar with a more old-fashioned sort of ditzy vocal affect.) In frequent flashbacks to their teen years, their get-ups are more reminiscent of Madonna-bes than the bland popular girls who torment them; in the present, they favor bright colors and shiny textures that look cartoonishly out of step with the rest of the movie’s 1997 world. The movie was perhaps ever-so-slightly ahead of the retro curve that spring: Boogie Nights hadn’t even finished managing the ’70s-to-’80s nostalgia comedown and The Wedding Singer’s all-purpose ’80s party didn’t arrive until 1998.

At the same time, Romy and Michele hedges a little on its ’80s bona fides, making No Doubt’s contemporaneous hit “Just a Girl” a soundtrack motif alongside “Turning Japanese,” “Heaven Is a Place on Earth,” and so on. Grosse Pointe Blank, on the other hand, really commits to its instant-classic soundtrack (a second volume was even released on CD, as was the style at the time). When the movie breaks from its hipper take on ’80s music, it’s only to make reference to Public Enemy and Morphine, leaving them carefully unplayed as an if-you-know-you-know sign that Debi (Minnie Driver), the high school sweetheart hitman Martin Blank (John Cusack) left behind, has great taste in music. This is something she shares, it’s implied, with Martin; he’s really the unlikely halfway point between Cusack’s characters in Say Anything and High Fidelity, and music is one lingering aspect of Martin’s old life that seems to give him nostalgic pleasure. It’s something like an inverse of Romy and Michele, who are steeped in their personal ’80s signifiers to the point of myopia (in the running gag/plot point about them pretending to invent the Post-It, it never occurs to them that it substantially predates their entire high school education) without ever seeming especially moved by the music of their youth (their big car singalong trails off when they admit to each other that they don’t know most of the words to “Footloose”). Their detachment—pretending to make fun of Pretty Woman while watching it dozens of times—is not the same as Martin’s detachment.

So Martin would not have hung out with Romy and Michele in high school; neither of them were in the “A-group,” as Romy and Michele refer to the popular kids. It’s hard to tell if Martin would be sharing a cigarette with Heather, the outcast played by Janeane Garofalo in Romy and Michele, because Grosse Pointe Blank is almost clique-agnostic in its look back at teenage years. It’s much more observant about the collection of strange individual personalities forced to coexist during that time. While some of the other reunion attendees are unpleasant, they don’t appear as malicious as Romy and Michele’s A-listers; Martin’s alienation isn’t intricately tied to their approval; and despite his initial reluctance to attend his 10-year, he’s too inward-looking to snark much in the direction of his classmates. There’s plenty of Cusack deadpan—and a funny scene where Jeremy Piven, playing a lost pal, immediately calls out Martin’s subtle dig at his profession as a realtor, jostling out an immediate apology. Most of the time, though, he reacts to life updates with a kind of wide-eyed curiosity: When Piven’s character reveals that another mutual acquaintance sold him his car, there’s genuine inquisitiveness when Martin asks: “Didn’t he break your collarbone and steal your woman?” Later, the professional killer defuses a physical conflict with the same overly aggressive guy rather than kicking his ass. Over in Romy and Michele, a reminiscence over a nerd they once pranked is more succinctly (though also hilariously) interrupted with one of them asking: “Didn’t he die?”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-