Walt Disney’s Century: Tron

In the midst of its wayward period, Disney decided to Tron for it.

This year, The Walt Disney Company turns 100 years old. For good or ill, no other company has been more influential in the history of film. Walt Disney’s Century is a monthly feature in which Ken Lowe revisits the landmark entries in Disney’s filmography to reflect on what they meant for the Mouse House—and how they changed cinema. You can read all the entries here.

“Won’t that be grand! Computers and the programs will start thinking and the people will stop!” – Dr. Walter Gibbs, Tron

We were one of the first families I knew to get a home computer. My father, always into computers, actually helped my elementary school to set up the Apple IIe machines where we learned typing and played stuff like Number Munchers and Oregon Trail. My childhood was spent figuring out how to get the damn sound cards to work on games like The Rocketeer or Monkey Island (which came on seven whole 3.5-inch floppy disks). Computers were some weird combination of fascinatingly unknowable and fun in the way a bucket of LEGOs or a closet full of art supplies or a pile of roleplaying game sourcebooks is fun: With a computer you could do anything you might imagine!

Tron lives in that time of wide-eyed discovery and possibility. Video games ate quarters, user interfaces were in monochromatic text, and we still believed software moguls when they said they founded their companies in their garages. It is a random, almost miraculous turn of events that Disney even made the movie at all, and while it was a modest financial success, it remains a foundational sci-fi movie. When we envision a digital world—some strange land inside of a computer that we can perceive and interact with from within—we owe something to Tron.

Even Cheech and Chong can’t resist this stuff:

The world’s foremost software developer is ENCOM, a company that occupies a massive corporate tower, flies people in via choppers with glowing accents, and, we find, was built on stolen intellectual property. The company is run by Dillinger (David Warner, whose presence in everything always screamed “bad guy”), but his strings are being pulled by his own creation, the artificial intelligence that runs the company, known as the Master Control Program (also Warner, with his voice distorted).

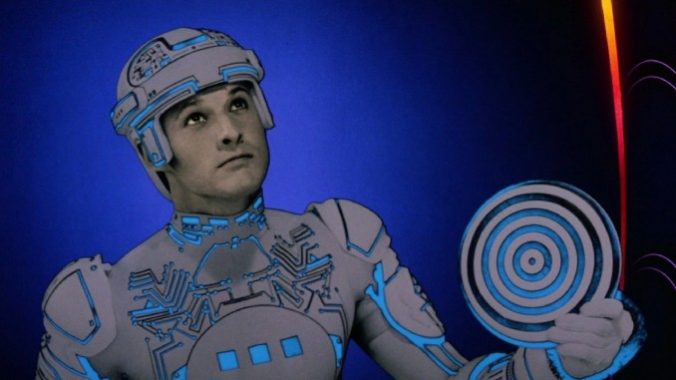

The movie opens with a view of just how oppressive the MCP is to the system it runs: Programs are anthropomorphized in the movie, within a partly animated, partly back-lit, partly computer-generated world designed in part by Blade Runner production designer and all-around-futurist Syd Mead, and French comic artist Jean Giraud, known as Moebius, who also contributed design work to the never-made Alejandro Jodorowsky adaptation of Dune. The MCP’s thugs capture programs and force them to compete in the games, gladiatorial combat contests that all have the feel of arcade quarter-munchers. The visual effects look dated, but here’s the thing: Of course they would. It’s set in the ‘80s, in a computer. Watching it again recently, it was kind of charming.

In the real world, a disgruntled former employee of ENCOM turned arcade owner, Flynn (Jeff Bridges), plots a way to break into the company’s systems and find proof that Dillinger grew the company by stealing his multi-million-dollar videogame ideas. (It is unclear if the games people are playing in the arcade are being populated by the programs in ENCOM’s systems, since the games at Flynn’s arcade are all exactly identical to the ones happening inside the computer world. The writers didn’t make it clear, and I guess you’re not supposed to think too hard about it.)

After a failed attempt to breach ENCOM that’s foiled by the MCP, Flynn’s antics raise the security level at the company, something that pisses off his old colleagues Alan (Bruce Boxleitner, who also plays the title character), Lora (Cindy Morgan) and Dr. Gibbs (Barnard Hughes). Gibbs in particular is righteously indignant that company employees are being locked out by the system, their programs subsumed into the code of the MCP.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-