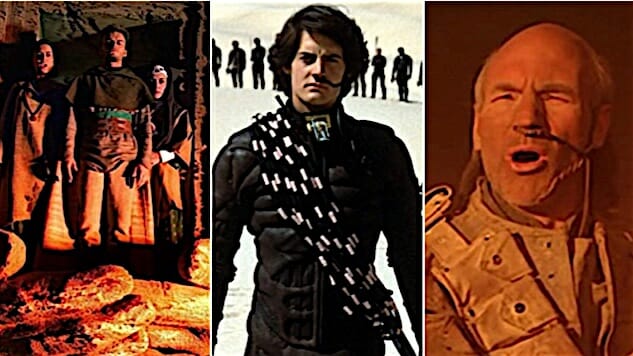

Return to Dune: A History of Dune Adaptations

Will a two-parter overcome the problems that have hobbled the novel’s many adaptations?

Reverend Mother: “Many men have tried.”

Paul: “They tried and failed?”

Reverend Mother: “They tried and died.”

It would take generations of genetic meddling, years of neurological martial arts training, and the aid of a mind-expanding drug to produce the sort of human being who could even imagine a Hollywood influenced by Dune instead of the Jaws– and Star Wars-chasing blockbuster industry we’ve been given. Considered the crown jewel of science fiction writing, Frank Herbert’s novel has proven either challenging or outright impossible to faithfully and satisfyingly adapt to the screen, depending on how you feel about the attempts so far.

As a result, I feel like a lot of the general movie-going public probably isn’t as familiar with the story as they are with, say, the backstories of superheroes. Merely describing the plot of the thing can make you feel like you’ve shed your clothes and donned a sandwich board and tin-foil hat, but, well: In a distant, interstellar future where feudalism and monopolistic capitalism abide under an emperor, and all travel and commerce depend upon a strange awareness- and mind-expanding drug called “spice” (because artificial intelligence went Terminator earlier and humanity has outlawed thinking computers, and safely traveling faster than light requires the ability to see through time and space and crunch insane numbers) which is only available on the planet Arrakis, also known as Dune. Dune is a vicious, arid desert planet with an oppressed and secretive indigenous people known as the Fremen, whose adversities and dogged determination have made them the baddest dudes in the cosmos.

As the original 1965 novel opens, the emperor plans to betray the noble House Atreides to their enemies, the violent and hedonistic House Harkonnen, essentially assigning the Atreides the brutal task of overseeing spice mining on Arrakis. The novel follows the young Paul Atreides as he and his mother barely escape the feud with the Harkonnens alive and fall in with the Fremen. The wrinkle in all this is that Paul is the result of ninety generations of careful breeding and political manipulation all aimed at making him the next stage of human evolution. Unfortunately for the schemers responsible, their plan worked, and Paul comes roaring back from his presumed death with an agenda of his own.

I’m not sure if that made sense, but I hope it clarifies for you why this particular intellectual property is so resistant to adaptation. Any one part of that premise I went into above depends upon a small mountain of lore that I—or a coherent movie with a runtime of less than 12 hours—could not possibly expound upon. This is among the densest texts I’ve ever voluntarily read, but the reason I’m far more excited about an adaptation of this than another boring-ass take on Great Expectations is that Dune’s vast and weird sci-fi setting wraps around a deliciously fun plot peopled with larger-than-life characters, punctuated by love and heartache and freaking knife fights. Squint at the right parts and it’s a surefire hit.

It’s for that reason that I understand the unbearable anticipation with which the far-flung fans of this franchise await the upcoming adaptation by director Denis Villeneuve, whose recent work you might recall I found to be thoughtful and intelligent. But still, could this be the one that breaks Villeneuve? Better men have tried.

Jodorowsky glimpses a different timeline.

“I wanted to make a film that would give the people who took LSD at that time the hallucinations that you got with that drug, but without the hallucinations.” —Alejandro Jodorowsky, Jodorowsky’s Dune

Though it’s the most recent development in the history of Dune film adaptation, it’s almost impossible to talk about anything that came after without starting with the film that never was. In the 1970s, Chilean-French director Alejandro Jodorowsky, fresh off two cult hits with El Topo and The Holy Mountain, was given carte blanche to do whatever the hell he wanted, and on the advice of a friend chose to adapt Dune. The impossibly ambitious project never came to fruition, and at this point never will.

If you’re a fan of the novels or at all interested in Jodorowsky’s work, you can rent the feature-length documentary Jodorowsky’s Dune for a very reasonable price from various streaming services and be taken on quite a ride. Teaming up with artists like Chris Foss and H.R. Giger—before Alien catapulted him into the nightmares of generations of moviegoers—Jodorowsky produced an entire art book with detailed storyboards and concept art, all with the express goal of showing the money men that he knew exactly how he was going to go about filming every single shot of his clown-sh*t vision.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-