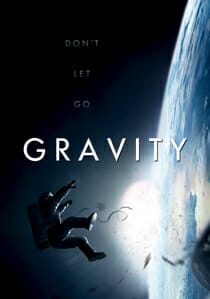

Gravity

Gravity is a revelatory, stunning cinematic experience. That’s more than enough to make it a great film, and a groundbreaking one, and yet director Alfonso Cuarón’s latest work can’t help but feel a bit disappointing at the same time. So much expertise and vision have been brought to bear, but in some ways the movie’s greatness only makes its flaws more noticeable. Gravity gets so close to being the astounding achievement it wants to be that it’s heartbreaking to watch it fall just short.

Probably the best use of 3D in a narrative film yet, Gravity tells its tense story in about 90 minutes, but the brutal intensity of its suspense is such that it feels much longer. It’s a cliché to praise a tense movie by saying you won’t be able to breathe while watching it, but that compliment has far more relevance when discussing Gravity since the movie’s plot is built around the need to find oxygen.

A team of NASA astronauts, led by veteran commander Matt Kowalsky (George Clooney) and inexperienced engineer Ryan Stone (Sandra Bullock), are orbiting high above Earth in the midst of repair work on a satellite. But their operation is cut short when mission control informs them that space debris is hurtling toward them, forcing Kowalsky and Stone to return to their shuttle. Unfortunately, they don’t get back in time: The debris tears the shuttle apart, killing the rest of the crew. Kowalsky and Stone are the only ones left alive, and with their oxygen tanks running low and communication with Earth severed, they must try to make their way to an orbiting space station before their air runs out—or they’re struck by another flurry of debris.

Cuarón has proved himself to be one of our most successful, fluid filmmakers, crafting a surprisingly thoughtful erotic drama with Y Tu Mamá También, producing a deeply dark sci-fi thriller in Children of Men and being responsible for the strongest installment of the Harry Potter franchise (Prisoner of Azkaban). His ability to meld accessibility with personal vision has been consistently rewarding and exciting, and for much of Gravity, he once again delivers muscular mainstream filmmaking with a poetic sensibility.

Working with longtime cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki, Cuarón never stops emphasizing the precariousness of the astronauts’ situation. Even before the initial debris shower, we get a sense of the vast, cold, airless emptiness of space that envelops the characters, leaving them with little margin for error if, say, their protective suits suddenly malfunction. Utilizing long unbroken shots that glide around Kowalsky and Stone, Gravity wants the viewer to be immersed in both the majesty and terror of outer space, and the 3D only heightens the immensity, which is important since physical distance between people and lifesaving objects like space stations becomes vitally important as the stakes escalate.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-