Happy Together: Guy Ritchie and Jason Statham Step Back from Their Blockbusters

With Happy Together, Jesse Hassenger examines collaborations between actors and directors that have lasted for three or more non-sequel films.

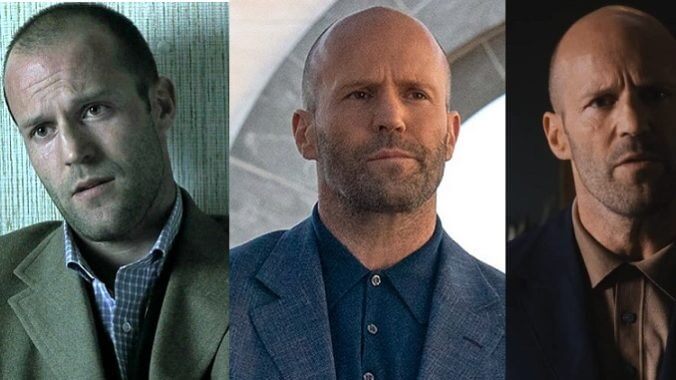

For several movies early in his career, Jason Statham blends in. Most of his trademarks are in place immediately: the balding-dome head, the gravelly cockney accent, the expression fixed somewhere between a wry deadpan and an intimidating glower. But in Lock, Stock, and Two Smoking Barrels, the 1998 Guy Ritchie crime caper that served as Statham’s big-screen debut, he’s one of many rough-hewn British lads; part of the plot hinges on mistaking various groups of scofflaws for each other. Statham isn’t even the only guy in the cast named Jason — nor is he the only Jason who makes it over to Ritchie’s follow-up film Snatch. He’s paired with his Lock Stock co-star Jason Flemyng, who was at the time the more recognizable actor, having appeared in Spice World, mind.

Yet in terms of leading roles, Statham has outlasted virtually all of his Brit castmates in either movie. (Brad Pitt and Benicio del Toro, obviously, are doing fine in that respect.) He has appeared in billion-dollar franchises like the Fast and Furious movies and all-star line-ups like the Expendables series; he’s starred in his own film series like Transporter and The Meg; he hasn’t slunk back to streaming-only programmers or television. Meanwhile, Guy Ritchie has found similar success: He kickstarted a well-liked Hollywood franchise (Sherlock Holmes) and directed a billion-dollar Disney movie (the live-action Aladdin). So it’s a bit unusual that Statham and Ritchie have only really crossed paths when scaling back down. Despite their many individual successes, the modest hit Snatch was only recently overtaken by Wrath of Man as their highest-grossing film together, helped along by two decades of inflation, and seemingly unlikely to be challenged by their latest film, Operation Fortune: Ruse de Guerre.

Ritchie’s career is too varied to claim that he turns all of his movies, big or small, into style-first exercises in cinematic cheek like Snatch. At the same time, Ritchie does have a way of circling around the idea of big-ticket entertainment, supplying more flash and attitude than traditional action-movie set pieces and payoffs. Think of how many of the best moments from his Man from U.N.C.L.E. remake have to do with tossing off action (like a boat chase that finishes up in the background as one character pauses for a snack) in favor of more fashionable imagery (like Alicia Vikander wearing cool pajamas and sunglasses). This tendency becomes all the clearer when examining his collaborations with Statham. Operation Fortune: Ruse de Guerre is the closest they come to a traditional star vehicle, and still extracts its greatest pleasures from smaller moments.

But let’s use some Ritchie-style scrambled chronology to jump back to Snatch, where it’s striking to re-examine Statham’s presence in light of the action star he would become. Though not top-billed, he narrates the picture, establishing him as a character who comments on the action at least as often as he enters the fray; he’s the literal voice of Ritchie’s self-amused ins and outs. His character, Turkish, is a fight promoter, rather than the fellow throwing punches; Turkish briefly brandishing a baseball bat is nothing like what Statham would get into a couple of years later in The Transporter, where he gets covered in oil and slicks his way through a fight with a bunch of literal axe-men. The Transporter trilogy is primarily a series of fights and chases featuring a genuine Olympic athlete, yet Ritchie’s movies assign the work of bare-knuckle boxing to the likes of Brad Pitt and Robert Downey Jr. rather than Stath.

Granted, Statham was a diver, not a boxer, and neither of Statham and Ritchie’s first two features are exactly action pictures, despite containing plenty of fisticuffs and gunplay. Yet as Statham established himself as a champion on-screen brawler in his Transporter series, fighting off axe attacks and knocking down doors, Ritchie still stubbornly refused to unleash him, instead placing him front and center for a turgid dud called Revolver that came out around the same time as Transporter 2. Revolver only sounds like the kind of gangster goof Ritchie was then best-known for; it’s more like Ritchie and Statham in permanent slow-motion, not a flourish but an affliction. Statham plays a criminal with a price on his head, recently released from prison while remaining stuck in another kind of limbo: a chin-scratching faux-psychological bullshit session revolving around faux-Buddhist philosophizing and Kabbalah symbology. (Ritchie was married to famed Kabbalah enthusiast Madonna at the time, and spends ample behind-the-scenes DVD time enthusing vaguely about “the concept” his movie is apparently bringing across.)

Outside of Ritchie’s orbit, Statham was proceeding like a kind of B-movie James Bond, splitting some characteristics of that British icon into a pair of 2000s franchise characters. Frank Martin of the Transporter trilogy has Bond’s shiny car and mission-driven ethos; Chev Chelios of the Crank movies is forced to indulge in Bondian levels of hedonism just to keep himself alive (which, come to think of it, is also Bond’s excuse). Statham further busied himself playing a variety of parts in on-screen heists, assassinations, and gambling excursions in movies of varying quality released at a steady, sometimes worrying clip. By the time he hooked back up with Ritchie some 15-plus years later, his first director had plenty of experience in a less niche-driven section of Hollywood, having made no fewer than four movies intended to jump-start some kind of franchise.

Indeed, why wasn’t Statham a part of Ritchie’s King Arthur project? Was he being saved for a future value-add to the planned franchise, the way he joined Fast and Furious as a part-six mic drop before serving as a villain, ally, and spinoff subject in subsequent films? Though it earns its rep as a misbegotten blockbuster wannabe, Ritchie’s Arthur is also pretty fun; much of it decorates his cheeky-bruv gangster sensibility with expensive fantasy trappings, and leaving Statham out of it just feels like a fundamental misunderstanding of the B-movie energy that keeps the film going. It was probably too much to hope for Statham playing a part in Ritchie’s Aladdin, turning that movie into a reenactment of one of Twitter’s all-time greatest threads; King Arthur, though, seemed doable.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-