It’s Not My Time to Go: Die Another Day at 20

Despite its 2002 release date, there are almost no mentions of or references to Twin Towers in the 20th James Bond film, Die Another Day. And while Die Another Day had other things on its mind in lieu of the War on Terror in a more literal sense—something that would change when the franchise would go back to basics with Casino Royale in 2006 and make it all textual—the film’s self-referentiality makes room for its own kind of twinning, albeit somewhat abstractly.

Die Another Day, with its much maligned invisible car and Easter eggs for other Bond movies, seemed to go out of its way to not be a post-9/11 Bond film. What allusion there is gets hidden in an ellipsis: After Bond is traded as a prisoner of war in North Korea, M (Judi Dench) tells him, “While you were away, the world has changed.” Paired with George W. Bush’s claim of North Korea belonging to the same “axis of evil” as Iraq, Iran and Syria, James Chapman, author of Licence to Thrill: A Cultural History of James Bond asserts this is where Die Another Day stakes its bona fides as somewhere along a War on Terror timeline. Like all real-world geopolitics in the James Bond movies, it’s a storm cloud that hovers forebodingly, but it’s seldom the main forecast.

The shaken cocktail of proximity to actual international affairs—close enough to grant the movies stakes, but far enough away to grant audiences the freedom of fantasy—has been a hallmark of the James Bond franchise for much of its run. That the films have frequently engaged, even if somewhat delusionally, with the status of Britain’s place on the world stage, a context whose veracity at some point became negligible, allows even the most hermetically sealed of Bond movies to play a game of Her Majesty’s snake eating its own tail.

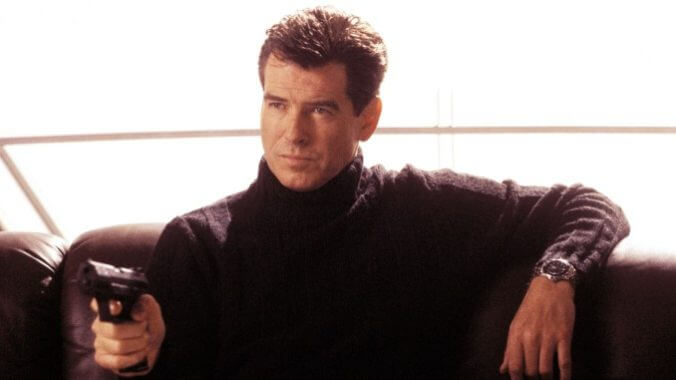

If the 20th Bond movie had been lambasted for its cartoonish reliance on CGI; for its sheepish zombification of another action movie of its era, XXX; and for its shameless product placement, what was Die Another Day if not a totem of what James Bond had become? Sure, Pierce Brosnan, still looked great in a tuxedo and, with a box office of $431.9 million, the Bond brand could still sparkle, but the temperature and attitude towards the series, once able to convey both the dream of a still-roving British Empire and the possibility of action filmmaking at its most competent, cooled considerably.

It was Brosnan’s fourth film, and the thing that has most stuck out to me about it, more than its fan service or even spiky femme fatale Miranda Frost (Rosamund Pike), was the grunt Brosnan lets out after being “saved by the bell” at the end of the pre-credits action scene. He hangs onto the bell’s tongue, with the son of North Korean general and conflict diamond trader Col. Tan-Sun Moon (Will Yun Lee) having driven over a dam to his death behind him, and when Bond releases and jumps to his feet, the squelch of stamina being squeezed from him is weighted down with the metatext of Brosnan’s real age betraying itself. The Irish actor was 49 at the time, younger than Roger Moore in his last outing as Bond in A View to a Kill in 1985, but the Bond films, like the world in which they ostensibly inhabited, had changed.

While the Bond films have always been a hodgepodge of adaptation and remixing, with Die Another Day taking elements from Moonraker (the wealthy impresario), The Man with the Golden Gun (the energy harnessing) and Kingsley Amis’ Colonel Sun (the villain’s name), it’s this very tradition that becomes a kind of working premise for the Bond film. For, if 9/11 wasn’t on the film’s mind, it was James Bond’s own longevity that was. The film’s release year was also an anniversary one, marking 40 years since Dr. No in 1962. In the gadget scene with Q (now John Cleese) alone, there are a dozen references to previous Bond films, from the poison-tipped shoe-blade from From Russia with Love to the alligator Bond uses as a stealth device in Live and Let Die. Die Another Day constantly asks itself how to manifest Bond’s legacy, and in moments it’s in objects, the tactile markers and signifiers of a secret agent whose iconography has become object d’art.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-