Will We Ever Learn from Walk Hard?

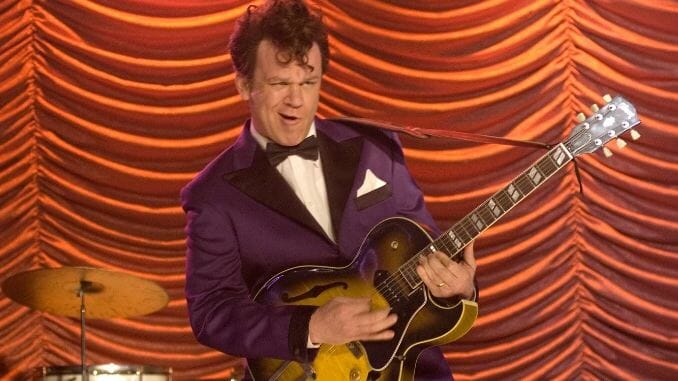

“Dewey Cox has to think about his entire life before he plays,” explains Sam McPherson (Tim Meadows), as Cox, the legendary country music star gears up for one last live rodeo. Bathed in melodramatic shadow, hand to the wall, head pensively turned down, Cox (John C. Reilly) takes us back to when it all began: His humble farm boy roots; the familial tragedy that defined him; his big break, crest to stardom and fall from grace; and all the women, drugs and vices scattered about as obstacles along the path towards eventual, late-career self-actualization. Does that timeline sound a little familiar? Dewey Cox wasn’t a real guy, but a satirical amalgamation of real artists and the hack movies made about their lives. Meadows’ line of dialogue is now one of Walk Hard’s most iconic; no less incisive now than it was over a decade ago, it’s parroted by those poking fun at modern music biopics and their cookie-cutter style.

So, what happened?

That question continues to plague the minds of many. In a perfect world, it seemed like Walk Hard: The Dewey Cox Story—a collaboration between Jake Kasdan and Judd Apatow, who worked together on Freaks and Geeks—should have killed the films it set out to parody and their paper-thin structure, recycled time and time again, each instance bequeathing less worthwhile results. Meant to satirize all music biopics, though specifically films of the time like Ray, about R&B legend Ray Charles and, more obviously, James Mangold’s Johnny Cash biopic Walk the Line, Walk Hard hit theaters on December 21, 2007. It received mostly positive reviews but was a box office bomb, taking in only $20 million against a $35 million budget. But it’s gained a staggering reputation, one that’s come to a head as music biopics have been enjoying another moment in the sun. Walk Hard’s increasingly resonant presence in pop culture now hangs on the periphery of every music biopic made in its wake. With every new music biopic, at least one person goes viral on Twitter just by questioning why these films continue to be made after Walk Hard put them in the dirt.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-