How the Jurassic Park Franchise May Have Ripped off a Children’s Book Author

As a child growing up in the 1990s, I went through a long period of infatuation—obsession, really—with dinosaurs. My love of learning about the extinct reptiles was no doubt an early indication for my parents of the geeky bookworm that I would become, and they responded by showering me with all the nonfiction and fiction about dinosaurs I could handle, graciously putting up with an imperious 6-year-old who demanded correct pronunciation of species names, as if the dinosaurs would be offended otherwise. Dinosaur books littered our home, and I absorbed an absurd amount of information that I somehow still partially retain now.

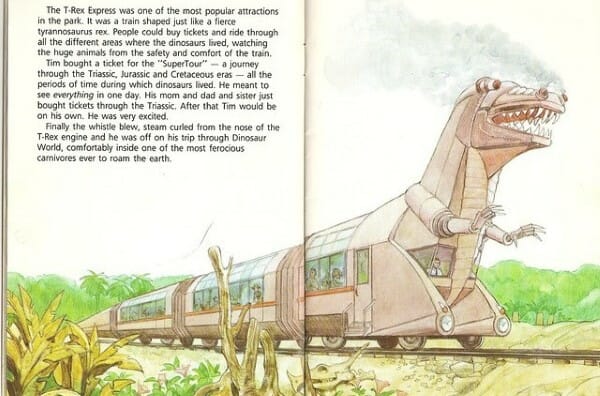

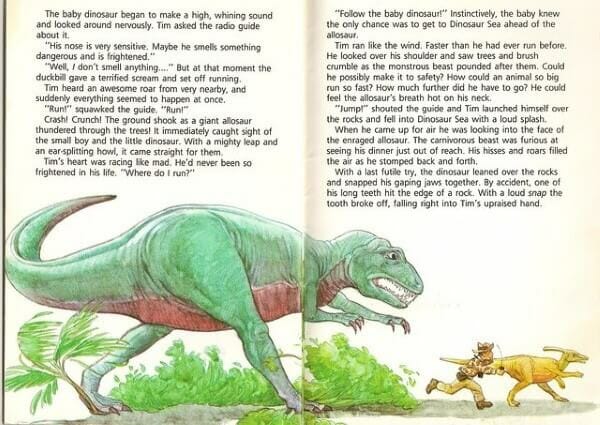

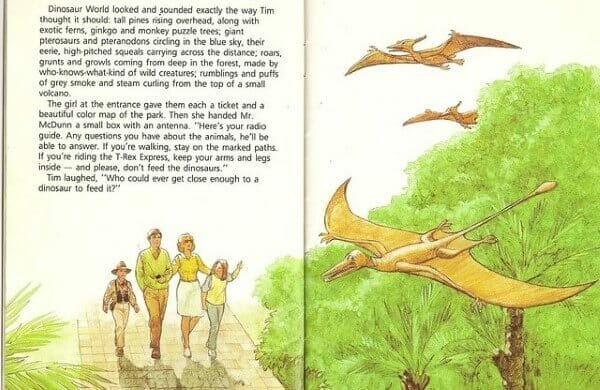

There was one book in particular, though, that captured my attention as a young boy—a fictional account of a futuristic dinosaur amusement park, fraught with danger and thrills. There were scenes of dinosaurs hatching in a nursery, where they were tended like domesticated livestock by uniformed park scientists. There were electric fences, and automated vehicles that shuttled guests around the park. There was a sage dinosaur expert, and a young protagonist named Tim.

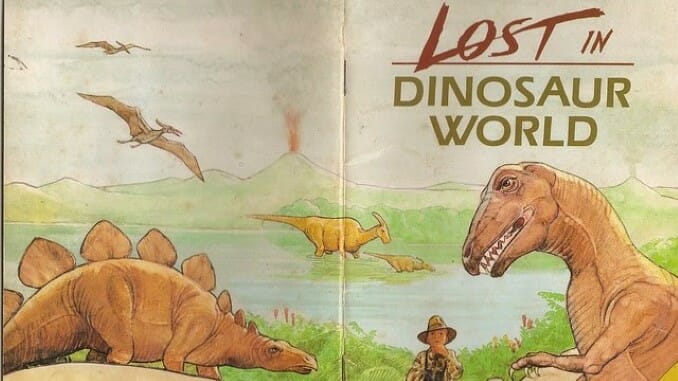

Was the book in question Michael Crichton’s classic 1990 novel Jurassic Park? Nope. Absolutely not. I was entirely too young to be diving into Jurassic Park in the early 1990s—what I had was the next best thing, a book called Lost in Dinosaur World by children’s author Geoffrey T. Williams. Here’s the thing, though: Lost in Dinosaur World was first published in 1987—three years before Crichton’s novel became a bestseller that would eventually be adapted as Steven Spielberg’s 1993 blockbuster. As author, Williams immediately cried foul, pointing to the numerous similarities between his work and the work of Crichton, and eventually Spielberg. And in the wake of the film’s massive success, a fed-up Williams brought a lawsuit against Crichton, Spielberg and everyone else in his way, attempting to prove that his copyright on Lost in Dinosaur World had been infringed upon.

Courts ultimately, and perhaps unsurprisingly, sided with the prolific and bestselling novelist, and his friend, the most astoundingly successful motion picture director in history, rather than a relatively unknown children’s book author. The Lost in Dinosaur World lawsuit faded into obscurity, and the Jurassic franchise has subsequently gone on to reap more than $5 billion at the box office alone, not even including the likes of merchandising and spin-offs. Those OG Jurassic Park lunchboxes weren’t free, you know.

But now, with Jurassic World Dominion looming, let’s take a moment to dive back into the strange similarities of Lost in Dinosaur World, an emblem of my childhood that just might have been ripped off into one of the biggest film franchises of all time.

An Adventure in Dinosaur World

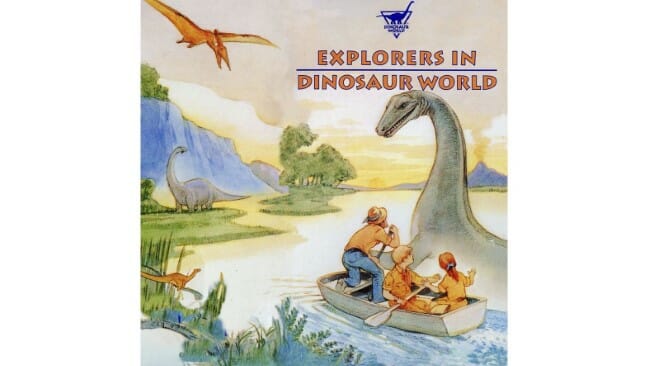

Lost in Dinosaur World was actually only one entry in a series of “Dinosaur World” books by author Geoffrey T. Williams, the second after the original Dinosaur World published in 1985, and followed by Explorers in Dinosaur World and Saber Tooth: A Dinosaur World Adventure in 1988. All four are short children’s adventure stories with some lovely, moderately accurate (in a scientific sense) illustrations, set in an amusement park/nature preserve that features real-life dinosaurs. The book is still available to purchase here and there online, and via Audible you can even hear the audiobook version that I absolutely wore out in a tape player as a dinosaur-obsessed 6-year-old. To this day, the ominous musical cues remain seared into my brain.

The goal of the Dinosaur World books is clearly to be both entertaining for kids and also lightly informative and educational, sprinkling factoids throughout that I can only imagine my parents grew very tired of hearing. Williams, in his lawsuit, described the setting as “an imaginary present day man-made animal park for dinosaurs and other prehistoric animals, where ordinary people can, in presumed safety, visit, tour and observe the creatures in a natural but high-tech controlled habitat.”

That certainly does sound almost indistinguishable from the setting of Jurassic Park, does it not? Williams certainly thought so, but let’s get a bit deeper into the actual events of Lost in Dinosaur World in particular.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-