The Bourne Identity Had the Useless, Brutal Security Surveillance State Figured Out 20 Years Ago

Not fight editing, though.

There’s a moment in every kid’s life when they discover that the adults in the room are just as clueless as anybody else. That’s usually a rough time. Worse is when you discover that the adults in the room are evil, and are in fact disdainful of the concept of good. The kids dragging themselves to school while their classmates and teachers die on ventilators have recently come to learn this sobering fact. For those of us of draft age in 2001, though, 9/11 was really the moment of epiphany. The ineptitude and laziness that led up to it, the furious scramble to put in place a useless security apparatus after it, the senseless choices to invade foreign countries when what was really necessary to bring the perpetrators to justice was already in place, all illustrated very clearly that the grown-ups just did not know what they were doing unless what they were doing was bad and wrong. They had endless, manic zest for that kind of thing, and no credit limit on making it happen.

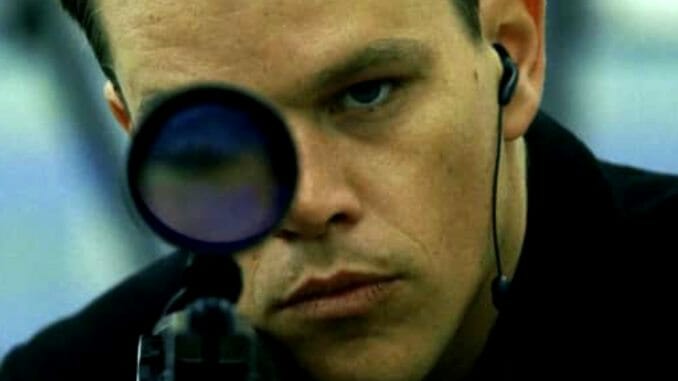

The Bourne Identity, which turns 20 this year just a little bit after the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq (which the United States spent trillions of dollars to definitively lose), is a fascinating watch today for several reasons aside from marveling at how little Matt Damon has aged. It’s the kind of film that big studios have basically stopped making anymore in favor of superhero films. There are surely visual effects or green screens somewhere in it, but if there are, you are generally unable to tell where. It is a movie with practical effects, roaring car engines, breaking glass, bloody fistfights and one good gratuitous explosion.

It is also a movie that has glorious, bone-deep, inspiring contempt for the U.S. security apparatus and the sneering bureaucrats who think nothing of spending $30 million dollars not on cancer research or new textbooks for Atlanta schoolchildren, but to make stupid weapons that, surprise surprise, leave trails of unnecessary and appalling collateral damage in other countries. The Bourne Identity and its two matter-of-fact, quite-good sequels ask “What if one of these absurd, unnecessary, wasteful weapons had its laser guidance system accidentally pointed at the guys who designed it? And the missile in question was Matt Damon’s fist?”

It’s a bit on the nose that a movie about a guy named “Bourne” begins with our protagonist pulled from water, awakening as a completely blank slate. Jason Bourne (Damon) has near-total amnesia. He can read, write and speak a babel of tongues, instinctively assess threats, and punch out Zurich police and field strip their stupid little guns without thinking, but he otherwise has no clue about his past life. He only learns his name is supposedly “Jason Bourne” after he follows up on a Swiss bank account number encoded into a laser thingy that was surgically implanted into his hip. (Admittedly, a Post-It would probably have been washed out, considering that the fishing ship that saved his life found him several dozen miles off the coast of Marseilles.)

Bourne also happens to be “John Michael Kane” and several other aliases, all represented by a rainbow coalition of passports stashed in the bottom of his safe deposit box, along with a hoard of cash and a handgun. He’s confused and scared about his situation. The Pentagon (or the CIA, or whoever it is) meanwhile, are alarmed: One of their top-secret one-man-army killing machines has gone missing and now seems to be gearing up to go rogue. Why else would he go clean out his stash after failing his mission to assassinate an exiled African leader (Adewale Akinnuoye-Agbaje)?

We are assured by a room of very annoyed white men—who wear a collective $10,000 in Joseph A. Bank apparel and whose heads warrant no more than a hundo of monthly expense at Great Clips—that this leader still being alive is extremely inconvenient for them. They’re even angrier somebody had the cojones to actually try to kill him (and worse, fail in a way that might hang it on them). One of those annoyed white men is Abbott (Brian Cox, who survives this film only to get schooled in the sequel). Beneath him is the unrepentant Conklin (Chris Cooper), the one directly handling Treadstone, Bourne’s black-ops outfit, and who immediately decides Bourne needs to die.

Nikki: He killed our man.

Conklin: Well, you’ve gotta clean that up.

Nikki: No, I can’t clean it up. There’s a body in the streets.

Conklin: So?

Nikki: There’s police! This is Paris!

Conklin is your favorite boss: He needs everything right now no matter what time zone you happen to be in, wants you to hack into things faster, and does not have any time anywhere on his calendar to talk about how literally all of this is his fault. There’s nothing flashy or showy in his performance. Very little that’s even overtly sinister. He probably has a wife and kid he’s planning to take on a trip to the Upper Peninsula in a week right after he’s done not tipping the housekeeper. Entitled arrogance is sort of the whole point of his character.

Desperate, confused, but way better at doing spy shit than any of these chumbolones, Bourne falls in with lost European drifter Marie (Franka Potente, whose death in the opening of the sequel is a crime). Conklin’s privacy-shredding surveillance technology has no idea what to do with poor Marie, who we’re introduced to as she’s trying to secure a visa and who’s barely had a stable address in years. Marie and Bourne lead the spooks on a chase across Europe, complete with car chases, fistfights and Matt Damon yelling at/killing a bunch of guys who are so reflexively violent, suspicious and cynical that it doesn’t occur to any of them that they could maybe try talking to him first.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-