Nobody’s Son: The Legacy of Dashiell Hammett

Dashiell Hammett’s detective fiction inspired the cinematic anti-heroes of the East and West

“Here we are, weakly caught in the middle, and it is impossible to choose between evils. Myself, I’ve always wanted to somehow or other stop these senseless battles of bad against bad, but we’re all more or less weak – I’ve never been able to. And that is why the hero of this picture is different from us. He is able to stand squarely in the middle and stop the fight.”

—Akira Kurosawa on his film Yojimbo

“The cheaper the crook, the gaudier the patter.”

—The Maltese Falcon, by Dashiell Hammett

Anybody can lapse into a parody of film noir or detective fiction almost on command. The deadpan worldview and gut-punch prose of the genre have long since joined the song “Born To Be Wild” among things that used to be revolutionary and now exist only to lampoon themselves. When kid-friendly productions like A Prairie Home Companion and Calvin & Hobbes can play with the grim postwar private eye, we can conclude it has lost its edginess.

But despite that, I don’t think a lot of people actually engage with the original work. Bill Watterson himself admitted to not having really read any of the detective stories that Calvin’s Tracer Bullet character spoofs.

“Tracer Bullet stories are extremely time-consuming to write, so I don’t attempt them often. I’m not at all familiar with film noir or detective novels, so these are just spoofs on the clichés of the genre,” he wrote in The Tenth Anniversary Book of Calvin and Hobbes.

It’s too bad. Before it was done to death, the hardest of hardboiled detective fiction inspired numerous touchstones of 20th century cinema’s treatises on the fatalistic pride of the Wounded Male Anti-Hero. A lot of it began with one thin, sickly man with a pencil mustache.

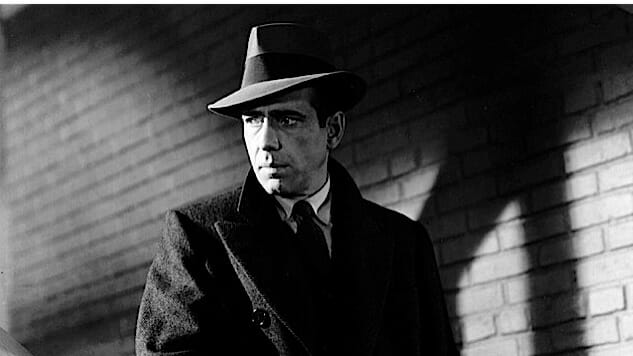

When Toshiro Mifune or Clint Eastwood or Humphrey Bogart stride into a hopeless fight with only their grit and our belief that they’ve just got to win, they’re many times following the dance steps of largely forgotten crime writer Dashiell Hammett.

![]()

“Who shot him?” I asked.

The gray man scratched the back of his neck and said: “Somebody with a gun.”

—Red Harvest, by Dashiell Hammett

A man (usually a man) rolls into a dust-choked town that looks like little more than a hole in the ground. We don’t know who he is, but we sense he’s dangerous. The casual cruelty of this town is put on display somehow: A dog runs by with a man’s severed hand in its jaws in Yojimbo (1961), a dead man with a sign tacked to his back rides out of town on the back of a horse in A Fistful of Dollars (1964).

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-