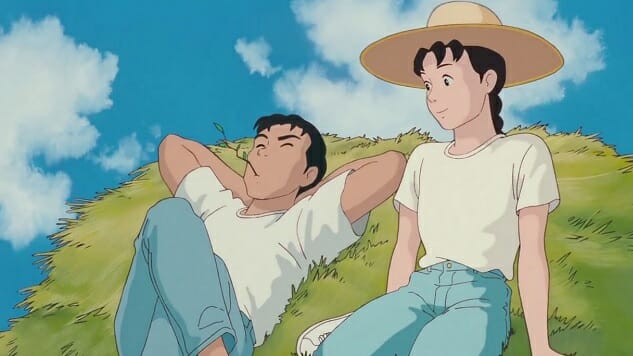

Only Yesterday

Only Yesterday is incredibly boring; Only Yesterday is incredibly captivating. Isao Takahata, Studio Ghibli’s co-founder and genius filmmaker, first released his wonderful ode to the rich complexities of a mundane existence back in 1991, but the picture failed to secure either a theatrical run or a home video release here in North America. No more, though: Only Yesterday opened in New York City on New Year’s Day and goes nationwide this Friday, so all Ghibli completionists and devotees can finally get the chance to see the film (and hear its English-language cast) for themselves on the big screen. For them, and anyone with even cursory admiration for the Ghibli name, the 25-year wait should be well worth it.

Only Yesterday does a lot of things, and it does all of them well. The film balances thoughts on everything from 1960s Beatlemania, to income inequality, to consumerism, to sexism against its overarching premise, which sounds banal to the point of tedium on paper but proves magnetic in practice. The film tells the story of Taeko Okajima in the past and present tense, flipping back and forth from memories of her childhood to her current state as an unsatisfied 20-something toiling away in Tokyo at a job she can only tolerate. At the movie’s onset, Taeko is going on holiday in Yamagata, where she plans to help out her brother-in-law’s family with the local safflower harvest. On her way to the countryside and even after she arrives, she constantly finds herself musing over flashbacks to her schoolgirl days in the 1960s.

As a girl, Taeko is voiced by Alison Fernandez. As a woman, she is voiced by Daisy Ridley, whose name is by now synonymous with Star Wars. Unsurprisingly, Ridley’s work here is quieter, smaller, and more muted than her work in The Force Awakens, but she is just as dazzling as she narrates her world through the filter of Takahata’s artistic lens. Takahata has made a rhythm-of-life movie with an accent all its own, though you can trace its cadence both back and forward through the years. The filmography of the great Yasujiro Ozu is an immediate influence on Only Yesterday, both in terms of its personal, familial scope and its idyllic backdrop: Late Spring, Tokyo Story and Floating Weeds in particular feel like immediate reference points here, but you can sense Ozu most, perhaps, in how deliberately Takahata structures Taeko’s journey. Only Yesterday is slow, but it is impeccably measured. Its two-hour running time doesn’t tick by as much as it stands majestically still.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-