Simply the Best: The Strange Legacy of 1932’s Grand Hotel

“People come, people go, nothing ever happens.” Those are the final words Grand Hotel leaves us with. The 1932 MGM film won Best Picture at the fifth Academy Awards and since then has found itself nestled into pseudo-obscurity. An ensemble cast of characters, intersecting stories and then a swift end. The film’s most notable aspect is its one strange honor: Being the only Best Picture winner to not be nominated in any other category. The film came, the film went and no fuss was ever made. But 90 years after its Best Picture win, it’s time Grand Hotel got its due. Its win was not a fluke, it was an acknowledgement of how Grand Hotel broke open how a film can work. Grand Hotel featured the first star-studded cast to ever grace the silver screen. The biggest names in Hollywood all crammed into one picture, an exhibition of celebrity itself. The Academy in 1932 understood what we have forgotten: Grand Hotel changed everything.

Grand Hotel is an adaptation of the play of the same name, both written by William A. Drake. MGM hired prolific screenwriter and director Edmund Goulding to direct, best known for directing 1947’s Nightmare Alley. Based on Vicki Baum’s German novel People in the Hotel, the film features the intersecting stories of a group of visitors to the Berlin Grand Hotel in classic portmanteau style. A sullen ballerina (Greta Garbo), a lovelorn conman (John Barrymore), an industrial General Director (Wallace Beery), a stenographer (Joan Crawford), a dying accountant (Lionel Barrymore), with a doctor (Lewis Stone) and the hotel’s porter (Jean Hersholt) rounding out the cast.

Once the technological spectacle of filmmaking passed, stars were the next aspect of movies the public latched onto. As early as 1909, there were calls to know more about the actors seen on the screen. Richard deCordova writes “the emergence of the star system can… best be seen as the emergence of knowledge.” People relied on their knowledge of who these performers were, and the exact types of characters they embodied. A star that continually brought in high box office receipts was the best bet for a studio’s success. But Grand Hotel came to be in the wake of the greatest shakeup to cinema since its inception: The arrival of the talkie.

Grand Hotel was made only four years after The Jazz Singer became the first feature with sound and “talkies” quickly became the main goal of most major studios. MGM was the slowest to switch, afraid its contracted actors wouldn’t be able to survive the transition. MGM was king when it came to talent, using the slogan “more stars than there are in heaven” to market its impressive roster. MGM’s first major sound film was 1929’s The Hollywood Revue, an exhibition of its best performers, and a decisive message that the studio would embrace sound by relying on their brightest stars. Plotless musical revues came into fashion with the advent of sound, spawning such franchises as the Broadway Melody films that began in 1929 that launched an entire genre. But The Hollywood Revue was notable in its sheer star power—MGM was going to use its biggest asset to its advantage.

It’s hard to imagine how all-star Grand Hotel’s cast was in 1932. The year the film was released, Greta Garbo was the highest paid talent in Hollywood. Wallace Beery won the Academy Award for Best Actor that same year and would be the highest paid actor for years to come (Grand Hotel was one of the last times he didn’t receive top billing). Lionel and John Barrymore were members of the most prolific acting family in history, performing in the same movie for the first time. Joan Crawford had made herself the defining star of the flapper era. Lewis Stone, with a miniscule part, had been nominated for an Academy Award three years prior. And Jean Hersholt had acted in 100 films prior to Grand Hotel. Castings that never came to be included Clark Gable in Wallace Beery’s role and Buster Keaton in Lionel Barrymore’s. It was about as star-studded as the sky could allow.

Grand Hotel relied heavily on the personas of its stars. Garbo, best known for her sullen and soulful characters, plays a sullen and soulful ballerina. John Barrymore is charming and Lionel is eccentric. Beery’s character is domineering and commands his screen presence. And Crawford is, of course, a smart, sophisticated, career-focused woman with a quick wit that hides an inner softness. Grand Hotel was designed as an exhibition, a highlight reel of the characters each actor could play in their sleep.

But Grand Hotel is not a lazy composition. The film remarkably assembles the best actors that transitioned from silent films to sound. The influence of silent film acting is very apparent, the main cast relying heavily on the histrionic acting style, using dramatic movements to convey thoughts without words. Lionel Barrymore scours his hotel room for his wallet, crawling around every corner, crying out his same desperate pleas. Garbo lounges and moves like she’s in molasses, but springs to life when she finds love. Crawford gives the best vocal performance of the cast, giving textured readings to her no-nonsense lines. In her last scenes, when she’s overcome with sorrow and hope, that softness she’s always been capable of glows as bright as it ever did.

The story structure of Grand Hotel is its most noteworthy element beside its talent. The intersecting character tapestry was not an original invention, but Grand Hotel became the most high-profile example on film at the time. It’s a story told in small moments, mimicking the literal revolving door of the hotel. Its scenes exist as dioramas of moments lost in a busy place, the story’s roots as a play shining through. Grand Hotel is also a pre-Hays Code film, allowing it more leeway when it comes to depicting more risque moral behavior. Characters gamble, affairs are being had, prostitution is heavily implied, and John Barrymore’s death is surprisingly violent. Goulding’s direction works in service of his performers and their intersecting moments. Occasional shots are noteworthy—like panning over the heads of the telephone operators as they connect calls or a tracking shot of guests approaching the front desk—but mostly the camera exists merely as a frame in which to view the tableau.

The 1932 reviews for Grand Hotel tell the story of a film deserving to go down in history. Variety described the movie as “the most impressive aggregation so far of strictly Bradstreet screen names.” (Bradstreet being a data analytics company that would chart the top box office stars.) It’s a crowd pleaser on every level, one that “doesn’t lean over backward on the artistic side” with “sure-fire human appeal.” And while compliments are given to Drake’s writing, the review contends that “this group of stars make the play something of a screen epic in a season of mediocre celluloid footage.” Variety’s short-lived female-oriented review section The Woman’s Angle even gives the film the go-ahead for the ladies, writing that it’s a “film that no well informed fannette can afford to miss.” The New York Daily News called it “superb.” Film Daily said it’s “One of the classiest moving picture affairs you’ve seen in a long time.” Glowing reviews in The New Yorker and The New York Times followed. Variety passionately recommended the film “even for the extreme length of nearly two hours.” At an hour and 56 minutes Grand Hotel pushed the barriers for how long a film could be, but length doesn’t matter. Grand Hotel is not just a film, it’s an event to be witnessed.

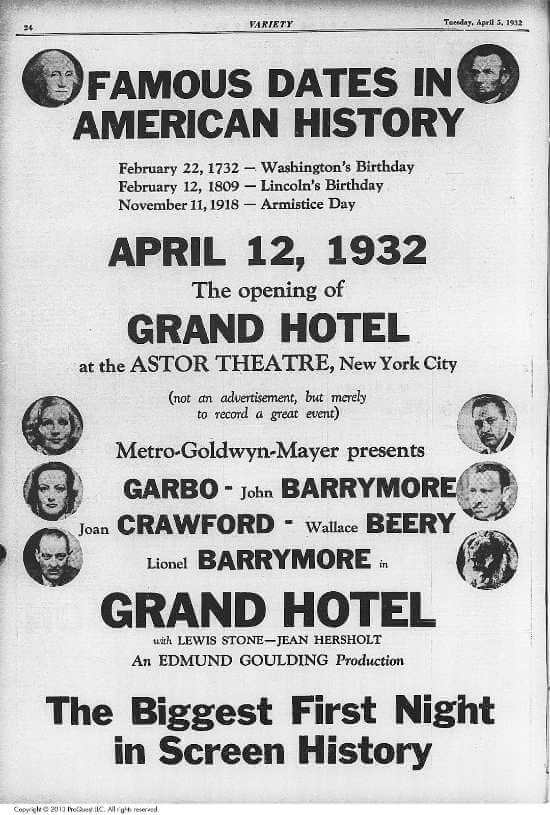

With glowing admiration, MGM pulls out all the stops for its premiere at the Chinese Theater. The event was a “mecca for the elite of Hollywood.” The front desk from the film was recreated and attendees signed the lobby guest book as they arrived. Promotional materials sent out ahead hyped up the day to the highest degree. One read “Famous dates in American History: February 22, 1732 Washington’s Birthday, February 12, 1809 Lincoln’s Birthday, November 11, 1918 Armistice Day, April 12, 1932 The opening of Grand Hotel.” A subheading describes the page as “not an advertisement, but merely to record a great event.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-