Every Park Chan-Wook Movie, Ranked

What tips you off that you’re obsessed with a director is all in the less glamorous side of film criticism. It’s not the verbose essays or incisive reviews, but the weird hunger you get to watch their new work, how many short films you can scour the internet for once you’ve gobbled up their features, and how relentlessly you badger those around you to join your obsession. You know that scene in Oldboy? The famous one where he charges down a corridor armed with a hammer and bludgeons his way through unlimited goons? That’s us bullying our friends and loved ones to watch Park Chan-wook movies – and ranking them. There’s zero difference.

The South Korean auteur made a name for himself with his meditations on revenge and his stylized glimpses at thundering violence, but what elevates his work from so many others is the tenderness that fuels all the depravity. It’s the doomed romances, the wounded vulnerability his characters show, and how much his films play to the senses. They don’t just want you to look at something beautiful, they want you to know what touching it feels like, what the specks of blood and brush of bodies against you would feel. Park has an unmatched eye/nose/ear for the breathless and soul-crushing, something his romance-mystery Decision To Leave takes to new heights.

Here is every movie by Park Chan-wook, ranked:

N/A: Trio (1997)

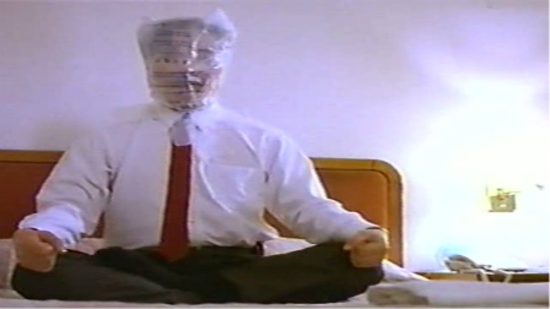

All the information as to the plot of Park Chan-wook’s sophomore feature, Saminjo (Trio), is as follows: “A suicidal saxophonist is pushed over the edge after he discovers his wife’s infidelity.” The film, sadly, is nowhere to be found online (legally). In fact, it’s unlikely it was ever translated into a language aside from Korean, or reproduced onto anything apart from VHS. There’s a 49-second clip of a VHS rip on YouTube, with a hilarious comment thread of seven different people asking for the full movie with subtitles, and no answers. There’s a Reddit thread of someone who claims to have a digital copy, and was asking around if anyone could contribute to a subtitle track. I tried to ask my friend to do the same but no dice. What’s more, Park Chan-wook himself is probably responsible for this, as he’s disavowed all of his feature work before Joint Security Area for being embarrassingly amateurish. Doesn’t look like Trio will end up on any comprehensive ranked list any time soon, unless a reviewer in Korea rents a hard copy.

10. The Moon Is the Sun’s Dream (1992)

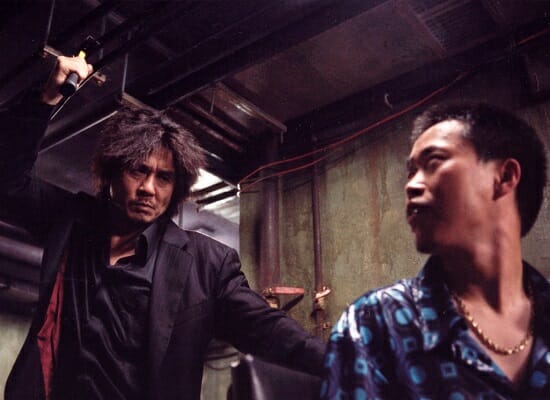

Park Chan-wook hates his first two films, electing to pronounce Joint Security Area as his actual film debut, and has voiced his desires to erase every copy of his preceding ones. Unfortunately, I am a completionist asshole, and sought them out anyway. The Moon Is the Sun’s Dream is a very low-budget melodrama about a photographer, a gangster and his girlfriend. There’s a lot of wry humor, little interspersions of violence and a tearfully tragic ending. There’s very little information to be found about this film, which is understandable for something that can only be seen in 720p on YouTube, but it’s not as bad a watch as Park die-hards have proclaimed elsewhere; there’s enough clever editing and camera trickery to keep your eyes engaged, and the trite story doesn’t ever feel completely insincere. Still, it’s miles below anything he’s shot afterwards, and it’s clear that, as his filmmaking interests matured, he had little interest revisiting stories that felt as cheap as this.

9. I’m a Cyborg, But That’s OK (2006)

Right after completing the Vengeance Trilogy, Park Chan-wook needed a break from traumatic violent flare and sought out lighter, gentler material. And so he turned to…a psychiatric hospital. While Park’s second collaboration with the powerhouse screenwriter Jeong Seo-kyeong turned out to be the most minor of their efforts, it proved another success for Park’s signature blend of grave, difficult topics with an abrasively light tone. Watching it as someone who’s dealt with their fair share of mental illness, it takes a lot to dismiss how much of I’m a Cyborg is dedicated to a series of “quirky,” idiosyncratic dramatizations of severe conditions; it can increasingly feel like these characters are othering mental illness rather than forging empathy with it. That said, Park and Jeong’s treatise on psychology is undoubtedly tied to the Korean culture in which they write, and when the climax comes about, it’s hard to deny the collective powers of these two storytellers. If there’s one thing that Park and Jeong love, it’s an unlikely romance.

8. Stoker (2013)

2013 was a big year for South Korean greats to English-language debuts, with Bong Joon-ho’s Snowpiercer and Kim Jee-woon’s The Last Stand, but thankfully Stoker is more similar in quality to the former’s quality rather than the latter’s. A crackling, hypnotic gothic drama that threatens to be off-putting on first watch, this marked Park Chan-wook’s first project he had no hand in writing (working from a script penned by Prison Break’s Wentworth Miller?!), but he more than makes up for it with a domestic drama that bears resemblance to A Tale of Two Sisters and pretty much nothing else Hollywood was making at the time. It doesn’t feel as dramatically polished or impactful as his Korean-language work, and you can sort of see every beat in the surrogate father/husband story playing out a scene or two before it comes, but there’s enough really unpleasant turns to keep you marveling from a distance at its strangeness. Plus, thanks to our protagonist’s extrasensory sensitivity, the stylism is cranked up to hypercharged levels; every sound is squeezed to its maximum allowance and the tiny imprinted fragments of images are jaggedly shoved to the forefront of our vision. There’s the Park we know and love!

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-