Square One: Sofia Coppola’s The Virgin Suicides (1999)

Whenever a filmmaker of note premieres a new film, it’s a good time to revisit that director’s first film to gauge how far he or she has come as an artist. With The Beguiled hitting theaters this weekend, we take a look back at Sofia Coppola’s The Virgin Suicides. (Spoiler Alert: the following article contains spoilers for Lost in Translation, Marie Antoinette, The Bling Ring and the main film under discussion.)

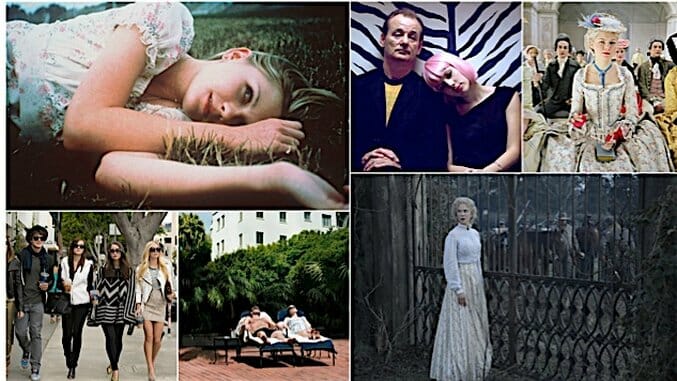

Sofia Coppola seldom tells us what the young women of her films are thinking. Not when it seems to matter most, anyway. In Lost in Translation, it is obvious that Charlotte (Scarlett Johansson) suffers from disillusionment, but in the intimate final moments between her and Bob Harris (Bill Murray), we are denied access to the words he whispers into her ear and are thus uncertain about her thoughts at the end of the film. Similarly, Marie Antoinette, despite making patent its titular character’s feeling of suffocation through oppressively opulent mise-en-scène and Kirsten Dunst’s subtly expressive performance, turns the queen of France into an inscrutable blank in the film’s coda, which observes the high tide of the French Revolution crashing against the doorstep of Versailles. Confronted with what is probably the most dramatic event of her short lifetime, Marie Antoinette is, unexpectedly, less readable than ever, facing a moment of crisis without betraying an iota of her thoughts to us. And in the courtroom-set scene near the end of the The Bling Ring, the originally spirited Rebecca (Katie Chang), the ringleader of a group of teenage burglars, appears cold and expressionless, confirming what we’d suspected all along—that her previously charismatic demeanor was all a front, a way of hiding her true self from the eyes of the world.

The height of Coppola’s tendency to obscure the inner lives of young women, however, occurred at the start of her career with The Virgin Suicides, which doesn’t merely incorporate the female mystery present in her later works but thematizes it. In the film, a gaggle of slack-jawed teenage boys hanker after the five Lisbon sisters, whose enforced aloofness (courtesy of their ultra-conservative mother) and seemingly ethereal beauty make the girls objects of fascination and obsession. “We felt that if we kept looking hard enough, we might begin to understand what they were feeling and who they were.” This statement comes from the narrator (Giovanni Ribisi)—one of the boys, now an adult and reflecting upon his youth—and encapsulates the two-pronged approach that Coppola takes to explore the film’s central motif of female unknowability.

On one level, The Virgin Suicides is about the sisters, “what they were feeling and who they were,” but more specifically, it is about how those on the outside—boys and men, especially—can’t ever fully understand such things. It is about respecting the mystery inherent to any person but especially to young women, a demographic too often doubly marginalized on account of their gender and youth. At one point in the film, a male doctor expresses confusion at why Cecilia, the youngest Lisbon sister (Hanna R. Hall), tried to kill herself, given that she supposedly hasn’t yet experienced the trials of adulthood. In response, she looks him straight in the eye and says, “Obviously, doctor, you’ve never been a 13-year-old girl.” Coppola, still young at 30 when she made her debut, has. And from The Virgin Suicides onward, the enigmatic quality of her female characters seems to have been designed, at least to some extent, to honor the private lives of young women.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-