The 25 Most Important Movies in Special Effects History

It’s true, on the most elemental level, that all one really needs to “make a movie” is a camera and a subject to point it at. Since the advent of the motion picture camera, people have been capturing footage in this way. But for just as long, they also yearned to depict things that didn’t yet exist in our reality. They wanted to dream up entirely new worlds, or infuse our existence with elements of the whimsical, fantastical or horrifying. And this is where special effects come to play in the art of filmmaking.

But what are “special effects,” really? It’s a term more loaded and generalized than it might first appear to be–indeed, in the modern filmmaking world “special effects” doesn’t even cover all the bases, as that term is sometimes considered apart and separate entirely from “visual effects.” The latter is typically used to describe the post-production digital effects work that now typifies any big-budget motion picture, while the former is a catch-all term that includes everything from mechanical effects, to traditional optical effects, to the use of prosthetic makeup and beyond. This is a field of extreme depth and artistry, a nesting doll of sub-fields and arcane niches that fuse together every combination of skillset imaginable. At the end of the day, perhaps it’s best to just call them all “FX,” while acknowledging just how deep that rabbit hole goes.

And in the last century plus of cinematic development, there are few fields that illustrate the story of film’s evolution with the same grandeur and creativity as the world of FX. Each film on this list serves as a milestone in its own way, and watching them in order is like going on a guided tour through the development of various techniques that would astound audiences and help to enshrine many of these movies as enduring classics to this day.

One thing is constant: Each of these films contains elements of special effects work that, at the time of their release, were truly awe-inspiring to the lucky patrons witnessing these films in a theater. So let’s dive into this appreciation of the art of movie FX, from primordial to state of the art.

Here are the 25 most important movies in special effects history:

1. A Trip to the Moon (1902)

Director: Georges Méliès

As a practicing stage magician, multi-hyphenate director Georges Méliès knew perfectly well the value of the arts of illusion and deception. It made perfect sense, then, for the pioneering experimenter in narrative film to incorporate many of these same elements into his work, most famously in the form of 1902’s fantastical A Trip to the Moon. Many techniques that we would today consider basic cinematic editing were at this point instead effectively thought of as special effects: The use of tools such as dissolves, multiple exposures, or even the basic substitution splice or “stop trick.”

What’s the “stop trick”? It’s really as elemental as it sounds: It’s when a director poses his actors in the middle of an action, stops rolling and then changes positioning or adds/subtracts something from the image before starting to shoot again, in order to surprise the audience. The technique was used in film as early as 1895’s 18-second short The Execution of Mary Stuart to simulate the monarch’s decapitation, but Méliès turns it to much more lighthearted and comedic purposes. His brave “astronauts” exploring the moon’s surface are befuddled by the things they find there, such as their umbrellas turning into giant mushrooms thanks to the stop trick. Suffice to say, cinematic FX would come a long way in the century to follow, but many of its most enduring techniques are found here.

2. Metropolis (1927)

Director: Fritz Lang

Film’s first few decades were a time of rapid development and evolution in terms of both narrative complexity and visual ambition. Here we are, two decades after the proto-narrative of A Trip to the Moon, and Fritz Lang’s magnum opus Metropolis is 153 minutes long in its original release, packed with every manner of special effect from start to finish. The mere concept of “making a film” has changed so dramatically in this period, it’s incredible to imagine being a filmmaker who witnessed this kind of breakneck evolution firsthand–the sky must have really felt like the limit, and the advent of “talkies” was just around the corner.

Special effects technician and pioneer Eugen Schüfftan left his mark on Metropolis in numerous aspects, with extensive use of miniatures in the titular city, along with matte paintings and the film’s iconic creation of the “Maschinenmensch” robot costume. Chief among the novel contributions of Metropolis, though, is the technique still named for its technician, the “Schüfftan process,” which involves partially obscuring the camera lens with a mirror to composite an image that combines live performers with miniature sets. In this way, Schüfftan was able to populate the city and bring the futurist dystopia of Metropolis to life.

3. King Kong (1931)

Directors: Merian C. Cooper, Ernest B. Schoedsack

In terms of films that were ultimately ahead of the FX curve, King Kong remains one of the most impressive examples. Thanks to the painstaking work of animator Willis H. O’Brien, combined with top-notch employment of matte painting, miniatures and especially rear projection, King Kong was able to bring to life giant monsters in a way that would barely be evoked with similarly powerful effect for decades to come.

Stop-motion animation is likely the technique that Kong remains most famous for to this day, employed in sequences like the iconic battle between Kong and the rampaging Tyrannosaurus of Skull Island, which took seven weeks of backbreaking stop-motion work to film. Willis O’Brien was an unmatched technician in the field, engineering new-to-film techniques on a daily basis throughout the filming of King Kong. Crucially, he was also passing on that knowledge to the likes of protege Ray Harryhausen, who would go on to make several contributions of his own on this list. At the same time, though, the FX work of King Kong also extends far beyond stop-motion, combining pioneering rear projection work and gigantic props in order to allow performers like star Fay Wray to interact with the great ape.

4. Things to Come (1936)

Director: William Cameron Menzies

Not so well known today as the extravagant excesses and incredible sets of historical epics like Cecil B. DeMille’s Cleopatra, the British Things to Come nevertheless employs the same sort of grandiose sense of scale, while tacking on the ambition to depict an entire century of technological progress in man’s future. Depicting author H.G. Wells’ musings on how human life might evolve (or degrade) from 1940 to 2036, it includes both a prescient look at a hypothetical second world war, and a hellish dystopian future evoking the industrialized, smoke-belching nightmare of Metropolis. The depiction of heavy industry and massive future machines and factories feel like a dire warning of humanity’s lack of empathy for the working man and the species itself as we hurtle toward a cold, bleak existence as cogs in an indestructible war machine. The miniatures work here is some of the most ambitious and monolithic you’ll ever see in any era.

5. The Wizard of Oz (1939)

Director: Victor Fleming

The effects of The Wizard of Oz are somehow so big, bright and in your face that the modern viewer almost glazes over them in the way we tend to do with current digital effects. How, for instance, does one realistically convey a huge tornado on the horizon in 1939? With 35 feet of muslin cloth wrapped around a steel gantry and sprayed with dirt via compressed air hoses, that’s how. That’s the kind of ingenuity that was being employed by FX director A. Arnold Gillespie on this movie, which also makes extensive use of matte paintings and fantastical sets. A personal favorite: The sequence of transition from sepia-toned black and white to glorious Technicolor was achieved in a single shot by painting the interior of a room entirely black and white and using a black-and-white painted body double for star Judy Garland. The black-and-white girl is seen only from behind, and as she exits the frame to enter the colorful land of Oz, she’s simply replaced by Garland stepping into the frame. It’s a classic example of the so-called “Texas Switch.”

6. Citizen Kane (1941)

Director: Orson Welles

There are certainly grandiose sights in Orson Welles’ iconic rise-and-fall story of Charles Foster Kane, but much of its technique is meant to be functionally invisible to the viewer while still affecting an almost unconscious sense of awe. Welles seems obsessed here with the creation of sights and images that “should be” visually impossible, but are achieved through clever use of techniques such as compositing multiple shots or employing rear projection to show something so seemingly small as a background scene through a window. Characters peer down from balconies at seemingly impossible angles. Kane bangs away on his typewriter while we clearly see Jed Leland’s face as he approaches from 50 yards away. The whole thing is an optical FX masterclass, and that’s before even getting into its nuanced use of age makeup to steadily transform the likes of Welles across an entire lifetime. The more you learn about filmmaking, the more astounding Citizen Kane tends to become.

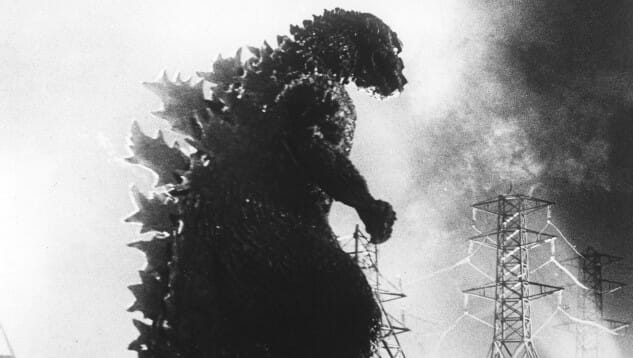

7. Gojira (1954)

Director: Ishiro Honda

The original Godzilla is perhaps unsurprisingly chock full of miniatures in particular, but that isn’t really its lasting FX contribution at the end of the day. Rather, it’s the way it fuses all its elements together — the man in the suit, the miniature sets, the reaction shots and forced perspective citizenry running for their lives — that brings those sometimes rough-around-the-edges miniatures to life. Honda and company were effectively creating a whole type of visual language here; the vocabulary with which one films a giant monster attack and the subsequent destruction. Techniques pioneered here would be used through the days of giant rear-projected atomic monster attacks in American films such as Them!, or The Giant Gila Monster, while the actual Godzilla costume would pass into cinematic legend, being tweaked and refined through the numerous sequels of Godzilla’s Showa Era until 1975. Suffice to say, there’s never been a subsequent giant monster movie that doesn’t owe Godzilla a debt, even if few have ever replicated its somber mood or gravitas.

8. The Ten Commandments (1956)

Director: Cecil B. DeMille

Not many directors ever have a chance to revisit one of their own works three decades later, bringing to bear the cutting edge of special effects in the process to do everything they wish they could have done the first time. Cecil B. DeMille, though, had just such a chance in his final feature The Ten Commandments, after having first directed a silent version way back in 1923. And this time around, no expense was spared, from the massive Egyptian palace sets, to the burning bush, to the main event: The Israelites’ march through the parting of the Red Sea. Considered one of the most complex and labor-intensive visual effects ever filmed at the time, the parting of the sea involved not only location shooting in Egypt itself, but also the building of a U-shaped trough at Paramount that held 360,000 gallons of water. It was the filling and dumping of water from these massive tanks, coupled with the filming of a huge waterfall on the Paramount backlot, that were composited together (and played in reverse) to achieve the effect of the vertical walls of water drawing back to let the Israelites pass. In terms of sheer power and spectacle, it was an effect difficult for anything else of the era to top.

9. Jason and the Argonauts (1963)

Director: Don Chaffey

The pioneering stop-motion special effects of Willis O’Brien, as seen in King Kong and Mighty Joe Young, were passed on to protege Ray Harryhausen, who took the art form to what many would consider to be its zenith in the 1950s and 1960s. In fact, the more time and budget Harryhausen had access to, the more spectacular the results he was able to achieve, first in giant monster films such as The Beast From 20,000 Fathoms, and eventually in what is often considered his magnum opus, Jason and the Argonauts. The film is rife with these effects, as in the battle between Jason and the many-headed hydra, or the titanic bronze guardian statue Talos. But Harryhausen’s Dynamation technique shines most brightly in the classic fight between Jason’s crew and a group of seven reanimated skeleton warriors, all of whom were hand-animated by Harryhausen and Harryhausen alone in a process lasting four months. Consider the fact that he needed to expertly match all of those skeleton movements to human choreography already shot, before using rear projection and split screen to seamlessly bring the images together. Very few artists have managed to replicate this kind of thing since, thanks not least to the backbreaking level of labor and passion necessary to do so.

10. 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

Director: Stanley Kubrick

When it comes to Stanley Kubrick’s 2001, it would probably be easier to go through it and note which pieces of FX work weren’t novel or cutting edge for the time. This film is one of those great, seminal watershed moments in the history of cinematic special effects, the kind of moment that raised the bar in a permanent way and made it far more difficult for other films in similar genres to live up to the same kinds of standards.

Audiences of the day were blown away by so many aspects of Kubrick’s starkly realistic envisioning of human space travel, achieved through a wide variety of means. There was, for instance, the 36-foot diameter centrifuge built for the production that contained many of the spaceship interiors, allowing for sequences in which the astronauts appear to walk on walls or ceilings in zero gravity. The palpable feeling of weightlessness captured here was something that viewers had never before witnessed, adding to the balletic precision one so often observes in Kubrick’s work. Then there are the groundbreaking uses of automated, motion-controlled cameras — and of course, the iconic “Star Gate” sequence in the third act, in which an astronaut entering an extraterrestrial monument is given the psychedelic trip of a lifetime courtesy of slit-scan photography. Audiences walked out of 2001 knowing they had just seen something unlike anything that had ever appeared in theaters before.

11. Jaws (1975)

Director: Steven Spielberg

The film credited with cementing the conception of the “summer blockbuster,” Jaws was a notoriously difficult and laborious production for a young Steven Spielberg. In truth, just about nothing went right, as the ambitious young director insisted that it should be shot on location in the ocean, making it the first major motion picture to do so. Budget quickly ballooned out of control, ending up at more than double its original figure, and crew referred to the film by a decidedly unimpressed nickname: Flaws.

The most famous source of headaches was of course the mechanical shark itself, and the tales of everything that went wrong with “Bruce” over the course of the shoot have been well established in Hollywood lore for decades. Subsequently, the shark’s many planned appearances in the film were toned down, with sequences like the opening nighttime attack on a lone swimmer instead being rendered in ways that showed the shark’s effects rather than its physical form. Spielberg has since concurred with the many observers who noted that the beast’s hidden nature in the film’s first two acts greatly amplifies the power of its eventual appearance once it engages in a battle of wills with the Orca. Particularly in sequences like the mad scramble and death of Quint, those remorseless, gnashing teeth and “lifeless eyes” retain the power to inspire more nightmares today than the thousands of CGI sharks multiplying in the deep in the decades since. Thanks to its timeless FX, Jaws feels just as vicious as ever.

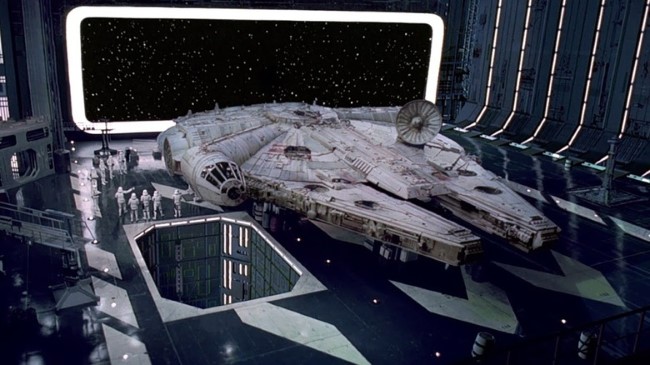

12. Star Wars: A New Hope (1977)

Director: George Lucas

As in the case of 2001, there are American movies before Star Wars, and American movies after Star Wars, and those two eras were subject to very different expectations from the audience. Before the film we now know as Episode IV: A New Hope, the audience point of reference for battles in space may have still been old Flash Gordon serials, or 1950s flying saucer pictures. George Lucas and the cutting edge technicians at Industrial Light and Magic changed all that, raising the bar of expectations to heights that would increasingly be unattainable for smaller productions. I pity the FX technicians working on Star Wars rip-offs as the decade came to a close, knowing they couldn’t come anywhere close to the FX first seen here, even as the approach of The Empire Strikes Back threatened to raise the bar once again.

Star Wars shines in many aspects of cinematic FX, including the skillful use of matte paintings to bring alien worlds and starships to life, and its impressive sets depicting everything from ship interiors and living quarters to alien dive bars. But it’s the miniatures that really bring Star Wars to life, the incredibly detailed and textured depictions of buildings and starships. The design aesthetic of those ships truly stood out as something novel in the era — not sleek and smooth, but bumpy and engineered, real space hulks sporting dirty “carbon scoring” and battle damage. The film wastes no time: From the very opening moments of Star Wars, the sense of scale, the immensity of that first Star Destroyer, evoke a setting filled with technological marvels.

13. Alien (1979)

Director: Ridley Scott

If the design aesthetic of Star Wars was notable for being a bit more on the dingy and “lived-in” side, then the world of Alien can only be described as downright septic. This was the most complete rejection of the spic-and-span nuclear age sci-fi aesthetic that audiences had ever seen at the time — the Nostromo of Alien is truly a hunk of junk, the equivalent of a desalinization plant or decommissioned oil tanker hurtling through the stars at the speed of light. It feels like a small thing to say now, but this was an immensely influential choice in terms of production/set design. As each hatch and rusted door of the Nostromo screeches open, it communicates to the viewer just how little care the mysterious “Corporation” has for its workaday, wage slave starship crew, a deeply cynical extrapolation of how corporate America would extend its philosophies into the stars and beyond. This is what space travel looks like when the bean counters care only about the bottom line.

And then there’s the titular alien, or the “xenomorph” as we all collectively agreed to label it. The nightmarish vision of Swiss artist H.R. Giger really can’t be credited enough, casting aside common animal and mythological inspirations to instead birth something that was more like an unholy fusion of biological and mechanical efficiency. Wreathed in what appears to be some combination of chitinous armor and corrugated plastic tubing, it feels as far away from human as any costume actually occupied by a human actor can really feel. Together, the ship and its stowaway combine to evoke what is simultaneously one of the most mundane and bleakly disturbing visions of humanity’s future.

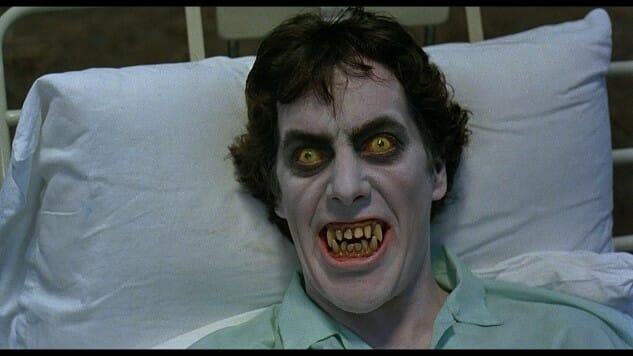

14. An American Werewolf in London (1981)

Director: John Landis

The 1980s were a high-water mark for many classic special effects disciplines, representing the peak of various techniques before the slow but steady advancement of computer-generated imagery would begin to displace any number of traditional FX techniques. By the end of the 1980s, in something like the fantasy feature Willow, a pivotal “morph” or transformation scene might be possible via CGI, but here in 1981 they still had to physically turn man to wolf in John Landis’ classic An American Werewolf in London, and the film is that much better off for the seeming limitation.

What follows remains one of the most iconic and painfully unnerving scenes in horror history, as protagonist David undergoes his first full-on werewolf transformation. Special effects and makeup maestro Rick Baker earned his first (of many) Oscars for the outrageously long and detailed sequence, sparing no expense or shred of empathy as we watch all of the man’s limbs elongate, crack and bend into terrible new forms. There have been many werewolf transformations in movie history, many of them more suggested than depicted, but An American Werewolf in London commits itself with sadistic glee to what looks like the most painful version of this process we’ve ever seen. The film itself is often cited as a horror-comedy, but that “comedy” is more a morbid brand of gallows humor perfectly represented in the savagery of the transformation — the only laughs are there because they have to be, as joking is the only alternative to breaking down into hysterics at the cruelty of it all. Becoming a lycanthrope has never seemed more distinctly unpleasant.

15. The Thing (1982)

Director: John Carpenter

John Carpenter’s The Thing was famously savaged by critics and detested by audiences upon release, with many calling it a depressing, nihilistic but simultaneously excessive affair, but the one area that engendered no complaints (beyond disgust) were its mind-blowing special effects. Those came courtesy of a merely 21-year-old Rob Bottin, who only a year earlier had provided the best non-American Werewolf transformation scene in The Howling. The Thing, however, would test him like nothing ever had before or since, and one assumes it was only his youth that got him through the grueling year he spent living on the Universal lot, during which time he was reportedly hospitalized for exhaustion and double pneumonia, among other things. He was heading up a project frequently spinning out of control, and improvising the entire time as he dreamed up a shape-shifting monster that far exceeded any of the plans Carpenter originally had for the film. Every conceivable technique and material was used to create the film’s goopy effects: Mayonnaise, creamed corn, K-Y Jelly and even microwaved bubble gum.

The result is transformation scenes that remain absolutely legendary to this day — many would still cite The Thing as perhaps the pinnacle of practical FX in the entire era, in scenes like Norris’ chest bursting open to bite the hands off Dr. Copper, or Norris’ head then stretching and sprouting crab legs in an attempt to scuttle away. Bottin performed labors of love here that will never be repeated.

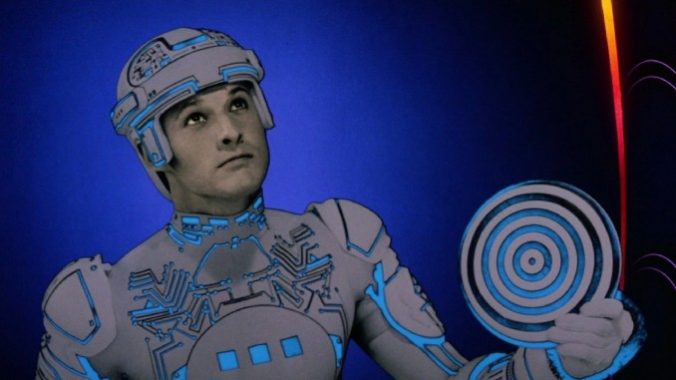

16. Tron (1982)

Director: Steven Lisberger

It’s funny to think that Tron might well have never come about if director Steven Lisberger hadn’t become infatuated with the game Pong in 1976. But he did fall down that rabbit hole, and it led to a unique vision that would take the resources of Disney to turn into a genuinely novel reality. Many times in a list like this one, we describe results as being “unlike anything the audience had ever seen before,” but in the case of Tron that’s almost an understatement. This film was bringing visuals to play that almost no one else had ever even conceived as a possibility, much less executed.

Granted, those FX only make up a small portion of the overall film that is Tron, which isn’t terribly surprising given the limitations the crew here was facing. Consider this: The rudimentary computer animation being created here was being worked up on a system with just 2MB of memory, and less than 330 MB of storage! And yet they were able to pioneer methods for combining backlit animation with 2D computer animation and live-action filming (in black and white, mind you), fusing them together into an aesthetic that would heavily inform the depiction of “cyberspace” for decades to come. You might think of this as computer animation’s big coming out moment in the world of cinema, and once the genie was out of the bottle there was never going to be any putting it back.

17. Who Framed Roger Rabbit? (1988)

Director: Robert Zemeckis

The films of Robert Zemeckis have frequently walked the cutting-edge path of avant garde visual effects, in ways both groundbreaking (Back to the Future) and legendarily disconcerting (The Polar Express). He is, in short, never afraid to venture into uncharted waters in search of a revelation, regardless of whether the result may well fall squarely into the uncanny valley. One of his most enduring successes, though, has to be the perfectly realized fusion of traditional hand-drawn animation and live-action photography seen in Who Framed Roger Rabbit?, a film that raised the bar in terms of the art of combining the performances of human actors with their fictional co-stars. None of it would work, of course, without the totally committed performance of Bob Hoskins as world-weary detective Eddie Valiant, and his ability to project maximum exasperation even when he was performing into thin air. In other moments, mime artists, puppets, mannequins and even robot arms were used to help human actors more perfectly interact with space that would later be filled with cartoon characters.

The technological marvels of Who Framed Roger Rabbit?, meanwhile, came into play on both the set and the long post-production process (14 months!), combining the extensive use of motion-controlled cameras with incredibly precise fusion of on-set practical effects (such as pyrotechnics) with cartoon images drawn to fit those moments in the months after shooting. A seemingly simple visual, such as the sparkly sequins of Jessica Rabbit’s nightclub dress, often provided the biggest challenges — an effect eventually achieved by filtering light through a plastic bag that had been scratched with steel wool. Inventive and frugal all at once, eh?

18. Terminator 2 (1991)

Director: James Cameron

From the moment it was conceived by James Cameron, Terminator 2 was always meant to be a true special effects showcase, one designed to show up the evocative but more rudimentary FX of the original film in every way imaginable. And it certainly had the budget to make it happen: At around $100 million it was the most expensive film ever made at the time, with more money set aside for visual effects and stunt work than just about any other production. And indeed, although a lot of contemporary adulation is still directed at the computer-generated effects that brought to life the antagonist T-1000, many of Terminator 2’s most jaw-dropping moments are the practical ones, such as its ridiculous truck crashes and pyrotechnic conflagrations. Go back and watch something like the minigun sequence just to appreciate the sheer volume of bangs, squibs and explosions being thrown around — to appreciate the hedonistic glory of traditional action moviemaking.

At the end of the day, though, it was of course the five minutes or so of the T-1000’s “liquid metal” form that really put Terminator 2 over the top as an FX marvel. Industrial Light and Magic coaxed every bit of horsepower out of their equipment in pulling it off, in a process so computationally intensive that it reportedly took 10 days for the equipment of the 35-person team to render a mere 15 seconds of footage. A lot of credit likewise belongs to the steely performance of actor Robert Patrick, whose lithe physicality and ability to readily swap between ultra-focused determination and false humanity made him a perfect foil to the more naïve Terminator played by Arnold Schwarzenegger. Little things, like Patrick learning to sprint without moving his face or visually breathing, help immeasurably in selling the indestructible menace of his character, even when visual FX aren’t being employed.

19. Dead Alive, aka Braindead (1992)

Director: Peter Jackson

We should note that advances in special effects technology, technique and inventiveness are by no means driven only by massive productions on the scale of something like Terminator 2. A blockbuster film helmed by the likes of James Cameron or Robert Zemeckis has the luxury of employing (and paying) the best artisans in the business to bring their worlds to life, but that has never stopped the most enterprising and hungry would-be auteurs from finding their own jury-rigged solutions to the same problems. Just ask someone like Sam Raimi, who made his name via Evil Dead and its DIY gross-out effects on a miniscule budget, paired with hyperkinetic camera work. Or you could ask none other than Peter Jackson, who somehow went in the space of a decade from shoestring New Zealand zombie splatter comedy to a trilogy of the most acclaimed, FX-laden blockbusters in history in The Lord of the Rings.

That Kiwi zombie comedy was Braindead, known to us stateside as Dead Alive. It captures the same irreverent, transgressive energy as Evil Dead and its sequel, but pumps the FX up to even more absurdly ambitious (and gratuitous) heights. Jackson must have known this would be the case going on, electing to shoot on Super 16mm rather than 35mm in order to save budget on film stock, electing to put as much cash into splatter FX as possible. And oh lord, how Dead Alive throws the blood and guts (and limbs, and viscera) around. There’s some grotesquely inspired puppetry and animatronics, paired with gaudy and fantastical lighting, and combinations of all of the above, such as the sequence of a zombified woman having a light bulb shoved into her head, which illuminates her from within like a lamp. But nothing can top the absolute carnage of the infamous lawn mower finale, and the reported 300 liters of fake blood subsequently sprayed over every possible surface. Even Raimi must have been impressed.

20. Jurassic Park (1993)

Director: Steven Spielberg

Jurassic Park was simultaneously a quantum leap forward in cinematic special effects in both the computer-generated and practical effects camps. At the time of its release in 1993, it’s easy to see why it was the computer-generated dinosaurs that were attracting the most attention–audiences had never seen such beautifully rendered and textured creatures on screen before, in sequences such as the raptors hunting the kids in the resort kitchen, or the T-Rex triumphantly bellowing under the falling Jurassic Park banner in the finale. This was a watershed moment on par with the likes of Star Wars, one of those magical blockbuster reveals when it immediately became clear to everyone involved that cinema was not going to be the same afterward. Computer-generated creatures were going to be held to a very different standard in 1994 than they were in 1993.

In retrospect, however, it’s the practical effects of Jurassic Park that remain the most potent marvel revisiting the film today, other than Spielberg’s effortlessly effective characterization. The animatronics are nothing short of stunning, bringing to life full-scale models of some of the most massive and awe-inspiring creatures that have ever walked the earth. The T-Rex animatronic head used in scenes like the rainy Jeep attack contains so much personality and nuance as we watch its pupils contract and the massive weight of its skull bear down on the car containing Lex and Tim. From the heaving breathes of the sick Triceratops, to the puckish, almost brotherly bickering of the raptors as they nip at each other, these animatronics mimicked the depth of personality found in actual creatures in a way that has rarely been replicated in the 30 years since.

21. The Matrix (1999)

Directors: Lana and Lilly Wachowski

The Matrix is, first and foremost, a brilliant method to fuse the high-flying, wire-aided action choreography of classical Hong Kong cinema — particularly the wuxia martial arts genre — with the hard-boiled cyberpunk stylings of William Gibson. The artificial world in which almost all of humanity resides, the titular Matrix, is such a gift to both action choreographers and special effects maestros for the essentially blank check of creative possibilities it promises. Anything can happen when it’s the chosen one destined to break free from the artificial simulation you’re depicting, and it lends real-world rationale to the fantastical action thus depicted within The Matrix. Each act of physics-defying action is an act of rebellion, an attempt to display mastery of mind over simulated matter. The famed bullet time effect, achieved via the compellingly named method of “time slice” photography, combined with pioneering use of virtual camera movement, is the soul of this philosophy — it imagines the depiction of something that should be impossible, via a method of filming that should also be impossible, at least as far as the audience understands it during the initial viewing.

But The Matrix simultaneously extends its visual effects influence far beyond some of its flashiest and most famous (and then endlessly copied and parodied) sequences. The look and texture of most every setting within The Matrix itself reflects the sinister tint of artificial reality, achieved among other ways through just-subtle-enough digital color correction, the same technology that would be much-publicized in the following year’s O Brother, Where Art Thou?. With that said, each subsequent release of the film on physical and digital media over the next 15 years featured vastly different color tones, making the “true” look of The Matrix (how green is it supposed to be?) into something of a riddle that was finally put to bed, more or less, by a 2018 4K remaster overseen by original cinematographer Bill Pope. It’s a point worth highlighting: Even a “complete” effect tends to continue evolving in the years after a film leaves the theater. Thanks to home video and the streaming world, FX remain living documents.

22. The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers (2002)

Director: Peter Jackson

Although the likes of Jurassic Park illustrated the possibility of human actors interacting with fully computer-generated, lifelike creatures in a way that looked near photorealistic, the thought of doing the same thing with a fully realized, pathos-infused main character in a film series was a bridge that took some time to cross. George Lucas certainly gave it a try via Jar Jar Binks in 1999’s Star Wars: Episode I – The Phantom Menace and we all know how that turned out. Even the dogged efforts of Star Wars geeks to revamp the reputation of every film in the prequel series in the years since can’t change the fact that Jar Jar was created as largely disposable comic relief, even with the most generous of interpretations. Gollum, on the other hand? This was the breakthrough in grafting computer-generated images to motion-captured performance that managed to take the stigma of digital characters away from the industry for the first time. And it was made by Peter Jackson merely 10 years after he was mowing down those zombies with the lawnmower in Dead Alive. What a quantum leap, right? We’re already on the record in calling the entirety of this Lord of the Rings adaptation an improbable miracle, one that was extremely fortunate to arrive in this precise moment.

It was Jackson’s own Weta Digital that shepherded these efforts to bring the first truly three-dimensional, legitimate CGI character to life. This was a process involving years of tinkering, and a major selling point for getting the trilogy made in the first place: They had to prove they could take the capering of actor Andy Serkis and transpose both the physicality and genuine emotional delivery to the “gangle creature” that is Gollum. And it all comes through in the face of poor Smeagol — the manipulation, the entitlement, the rage, the fear, the deep-seated but ultimately hopeless desire to throw off his worst impulses. Never had audiences been able to read so many nuances in the face of a computer-generated being.

And it doesn’t stop with Gollum, either, as The Two Towers also broke ground on vast improvements to the depiction of huge, computer-generated crowds, allowing for sweeping vistas at the Battle of Helm’s Deep that seemed to show hundreds or thousands of soldiers all engaged in independent motion and combat. All told, it was a massive milestone in the evolution of visual effects, existing capably alongside old-school Hollywood practical effects trickery.

23. The Curious Case of Benjamin Button (2008)

Director: David Fincher

Some day in the future, we’ll likely find ourselves explaining to kids that the age of a performer was once a major factor — the major factor — in determining what kinds of movie roles were available to them at any given time. Through the use of makeup, one could stretch the window of viability to some degree in either direction, but only in rare instances could someone who is objectively the wrong age for a part be expected to portray a character. And when they ask how this all changed, The Curious Case of Benjamin Button is the film we’ll be pointing them toward. It wasn’t the first to combine practical and digital methods for aging and de-aging a primary character, but it was the first film to blend those styles of FX in a way that was so seamless, the audience was able to effortlessly suspend its disbelief. In doing so, it paved the way for the semi-blasphemous current digital model, for better or worse, which effectively lets performers in the latest MCU entries play any age the screenwriter wishes. Age has never been more accurately described as “just a number,” at least when it comes to Hollywood casting departments.

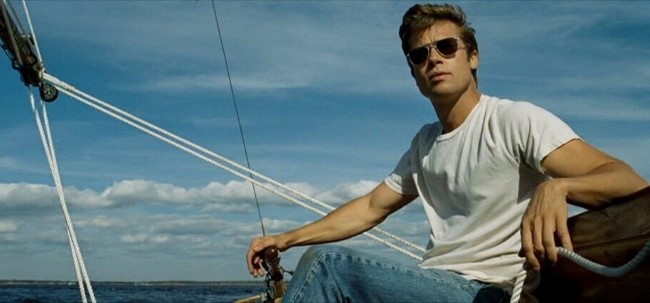

The work in Benjamin Button, though, is often beautifully subtle. The more ostentatious bits are what stand out, particularly the film’s early scenes with a withered Brad Pitt (a perfectly central 45 years old at the time of shooting) attempting to caper like a young boy. But it’s the central meat of the film, the moments when the FX are rendering him at 5, 10, 15 years from his current age in either direction, that really stand out for their pathos in retrospect. It gets a lot of emotional mileage out of Pitt’s “descent into youth” and the concrete certainty of impending death.

24. Avatar (2009)

Director: James Cameron

![]()

The discourse leading up to the release of the long-delayed Avatar: The Way of Water in 2022 was a funny thing. Across the internet, detractors of James Cameron’s first film had vociferously claimed for years that Avatar had been an extreme aberration of interest in 2009, a surge of curiosity created by cutting edge visual effects, and that the film had ultimately had “zero cultural impact” in the decade plus that followed. They ignored such elements as the widely reported stories at the time of “post-Avatar depression” among the film’s fans, real life people who were so distraught about not being able to live in the symbiotic world of Pandora that they were left feeling suicidal at the prospect of returning to our own human society. So no, it was never fair to say that Cameron’s film somehow lacked “cultural impact,” any more than it lacked influence on the next decade of blockbuster filmmaking. Rather, it became the new template for what a truly massive, CGI spectacle would really look like, remaining more or less unsurpassed until its own sequel finally arrived in 2022.

Consider: It was only seven years earlier that Gollum was making history as the first really three-dimensional, fully nuanced character composited from computer-generated imagery and informed by the performances of motion captured actors. Seven years, and now practically everyone in Avatar falls into the same category. That is an exponential leap of complexity, in a very short time. To kids of the 2000s, it’s safe to say that this was their Star Wars moment.

25. Mad Max: Fury Road (2015)

Director: George Miller

Much has been made of the incredible practical effects present in Mad Max: Fury Road over the course of the last decade or so, especially by a particular camp of cinematic FX purists who hold the film up as a sacred object to ward off the taint of what they tend to describe as CGI dominance. And yes, there are amazing in-camera FX captured here, from an entire legion of spiked desert vehicles, to Cirque du Soleil acrobats swaying on swinging poles in the wind, to an actual guitarist in a swinging harness, shooting streams of real liquid fire from his flamethrower instrument. But the achievement of Fury Road goes beyond simply the ridiculously complex (and ridiculously dangerous) practical FX and stunts department to the overall visual incarnation of George Miller’s fantastical imagination itself, which required the synthesis of both roaring slabs of metal and CGI visuals heightened to the point of apoplexy.

Fury Road stands out today as one of the most “visually engineered” films ever made — only the desert itself calls to mind anything from our own reality, and most depictions of that desert in the film are replete with expressionistic CGI backgrounds, or storms, and dramatic color correction. At every moment, the visuals of Miller’s film call attention to themselves, highlighted by his own use of dramatically scaling framerate from moment to moment, which he tweaked to allow the audience to see exactly as much of any given effect as he decided was appropriate. Together, they form a garish ballet of twisted metal, electric orange explosions and savage survival, an undertaking that was both incredibly expensive and draining to everyone involved. It’s only natural to assume that Miller’s upcoming Furiosa film will be held more in check by studios unwilling to go through that kind of development hell again, but perhaps he’ll manage to surprise us one more time.

Jim Vorel is Paste’s resident genre movie guru. You can follow him on Twitter for much more film content.