Our Stupid World Has Made The Postman Relevant

Costner’s second over-ambitious post-apocalypse film finally finds its moment to shine.

I watched The Postman once when it came out 23 years ago and have never laid eyes on it since, and yet in the intervening years I seem to have remembered almost all of what’s notable about it. This is baffling to me because its main sin is that it’s far too long (three hours?!) and too boring—the scenario just doesn’t call for such an epic runtime. And yet, its one-note characters are distinctive, its silly lines are delivered with conviction, and its racist/nationalist/survivalist bad guys don’t get to hide behind implication and innuendo as we are shown why they are evil sacks of shit. Characters with names like “General Bethlehem” and “Ford Lincoln Mercury” stare each other down in this thing, and it’s all totally in earnest.

It is a considerably better movie than it got credit for back in 1997, when it was savaged by critics and flopped in theaters. Evidently it has not been forgotten: people have been joking about it on Twitter ever since word began to get out that now, in 2020, the postal service is under threat.

As the president flagrantly and openly declares that he has sabotaged the U.S. Postal Service to better his chances in an election, with plague ravaging the country and one political party all but openly courting white nationalism, The Postman is suddenly, for the first time ever, a relevant movie.

There is truly no indignity we as a nation will not be made to suffer, it seems.

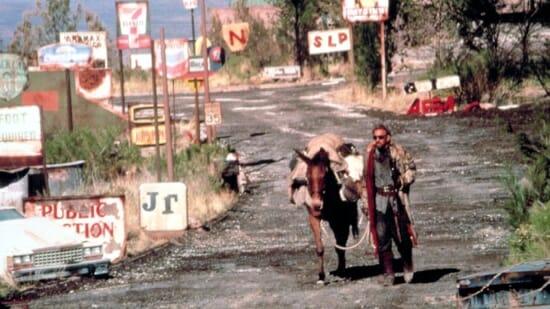

Set in the distant future of 2013, Costner plays an unnamed drifter wending his way through the pristine Pacific Northwest of a fallen United States, with only his loyal mule Bill to accompany him. Costner’s chief weakness during these times is that even when he’s trying to play a cranky loner, he still seems avuncular. Performing Shakespeare in exchange for thin gruel whenever he drifts into a town, he’s abducted and pressed into the Holnist army, a pack of white supremacists led by General Bethlehem (Will Patton). We know they are white supremacists because Bethlehem is clear that his involuntary conscripts must be of the right ancestry and one of the other captured men who is of mixed race gets called a slur by one of the true believers. The bastards even cook Costner’s mule with a snide line about how it’s impure.

After seeing firsthand the deranged, hyper-masculine feudalist fantasy he’s up against, Costner slips the leash and escapes into the wilderness, where he discovers a postman’s uniform and a sack of undelivered mail and decides to try to con a small town with talk of being a representative of a reformed U.S. government. He seems to be on the verge of getting shot by a local sheriff before his gambit pays off. Every scene in this thing is over-dramatized, including the one where the very eldest member of a walled-off Oregon community hears her name in Costner’s desperate mail call and the hope-starved residents decide he’s legit.

Because this is also a vanity project, Costner falls in with an adoring young woman, Abby (Olivia Williams), who wants his seed—it’s okay, her husband is sterile and he’s totally doing her a favor! Not long after he rolls on, she’s captured by Bethlehem and her husband murdered before her eyes. We breathe a sigh of relief later when she reveals to Costner that Bethlehem never succeeded in raping her because the guy was impotent the whole time—so on the one hand the movie is reassuring you that its fertile young love interest isn’t damaged goods but on the other it’s pointing at the KKK’s collective junk and snickering, and you wonder how much more of this well-meaning movie you can take.

Costner, who by now has taken his grift regional, rescues Abby from Bethlehem and passes a long winter in hiding with her. Digging out with the thaw, the two encounter painfully earnest postal carriers who are being organized by the young man who insisted Costner swear him in as a letter carrier, Ford Lincoln Mercury (Larenz Tate), and Costner realizes he’s inadvertently kicked off an effort to revive pre-apocalyptic society.

It is unforgivable, really, to watch some of these scenes and for the very first time take their earnestness at face value. Ford has organized dozens of postal service routes throughout Oregon, created a sorting center where little baskets and cubby holes with the handwritten names of towns on them are visible, and seems to be bossing the food and ammo responsibly and democratically. His multiracial cooperative stands in contrast to the violence of the might-makes-right Holnists. It inevitably leads to a war between the two factions, one Costner prosecutes with the help of a former Vietnam vet.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-