The Lost, Weird Art of Vanilla Sky

Last year marked the 20th anniversary of Cameron Crowe’s seminal film, Vanilla Sky, a film I watched and then rewatched for the first time this month. My viewing of the film came during a dire time in my life, early in February when I was still feeling jaded by the year’s recent Sundance output. I had mostly been doing rewatches of films that I loved, or first watches that were either flat-out bad or not quite exhilarating. Everything changed for me after watching Vanilla Sky, a movie that, ironically, was adapted from a Spanish film that played at the 1998 Sundance Film Festival.

I feel like it’s possible that everyone is born implanted with a loose cognizance of Vanilla Sky, because it feels like I have been aware of the film for most of my life. The movie has certainly held a weird, nagging little niche in my mind since around middle or high school; that image of a wistful Tom Cruise staring off into the distance flanked on all sides by a picturesque, Mac screensaver background, his eyes following me as I downloaded songs from the soundtrack off of Limewire. But I never really knew what Vanilla Sky was about (what a treat for me, then, to finally witness at the ripe old age of 27). I knew it was a film that maintained something of an odd reputation over the years, and that Crowe infamously freaked it with the track list. I also knew that it was a science-fiction film, even if, as I watched it, I struggled to understand how it fell into that genre before I arrived at the final act. Simply put, they don’t make them like this anymore.

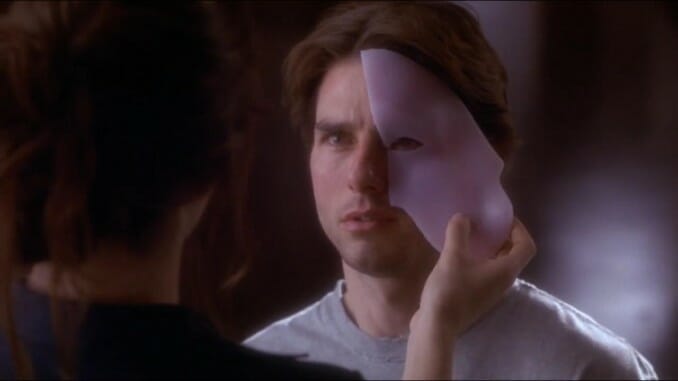

Having now seen Vanilla Sky, it’s a movie that I don’t think could ever truly disappear from the cultural consciousness even if the creators desperately tried to remove all traces of the thing. I firmly believe that if the world ended tomorrow, Vanilla Sky would still persist, like a dream held tightly in the back of one’s mind that the dreamer can no longer discern from reality or memory. Or, perhaps, even more appropriately, like the intrusive vestiges of David Aames’ (Cruise) former life that antagonize him and turn the lucid dream that he chose to embark upon into a nightmare. This is after falling in love with Penélope Cruz, after his quasi-lover Julie Gianni (Cameron Diaz) attempted to commit murder-suicide with him in her car and disfigured his beautiful face, after having committed suicide, and after being cryogenically frozen—by which point the movie had already turned into 10 different movies that reveal themselves like Russian nesting dolls across the narrative.

I was only six when it came out, but I’m positive that I’m not the first person to watch or revisit Vanilla Sky in the past few years and come away with a more acute feeling than ever that things—in the film industry, but also everywhere—are worse now. It’s a film that could only have been made at the turn of the millennium: That post-Matrix technological and existential fixation with finding oneself trapped in an artificial world, during a time when Tom Cruise was still at the top of his game and eager to make dramatic movies with auteurs (though, at this point the Mission: Impossible domino had already been struck down), when Jason Lee and Cameron Diaz were still sought-after cinema regulars and, of course, when a mainstream, Hollywood movie as insane as this could have been made with any budget behind it at all. I hate to be the kind of person who says “watching this piece of art is like being high” while having watched it stone-cold sober. But watching Vanilla Sky is truly like being high and having your high mutate from euphoria, to hilarity, to paranoia, to fear, to calm fatigue, right before you finally nod off into a deep and blissful sleep.

For those unfamiliar, Vanilla Sky follows Cruise’s David Aames: Wealthy heir to his late father’s publishing company, which he struggles for ownership of alongside a board of shareholders he refers to derogatorily as “The Seven Dwarves.” On the side, he has a not-quite-romantic but very much sexual relationship with a woman named Julie Gianni (Diaz), who views their relationship as both very sexual and, unbeknownst to David, very romantic. At a party, David’s best friend Brian Shelby (Lee) introduces him to Sofia Serrano (Penélope Cruz), who David quickly falls for—much to the chagrin of Julie. Scorned by David and, apparently, deeply unstable, Julie offers David a ride to work the next day, having followed him from his party to Sofia’s apartment where he had spent the night. After espousing an absurd monologue—in which Diaz has to utter the sentence “I swallowed your cum, that means something” with the kind of complete and total sincerity that got her nominated for numerous awards that year—Julie intentionally loses control of the vehicle and crashes the car. Julie is killed in the crash, David is left permanently disfigured and, suddenly, he must now navigate through life as a shudder weird and ugly person while he develops an increasingly passionate romance with Sofia.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-