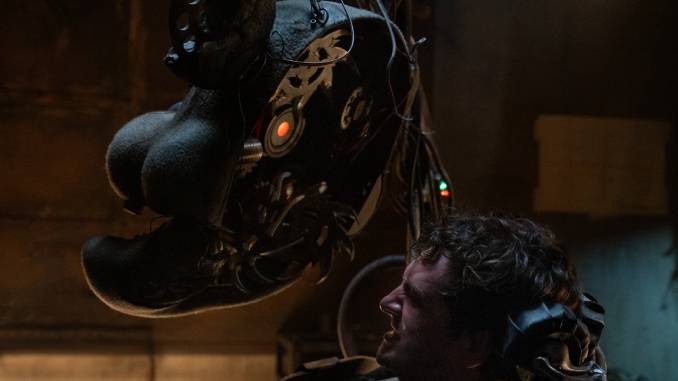

Five Nights at Freddy’s and the Allure of Let’s Play Cinema

The first time I played the horror game Amnesia: The Dark Descent, it was in a proto-livestream setting. I had my computer hooked up to the living room TV of a friend’s college apartment. We’d turned off the lights, drawn the curtains and poured ourselves drinks. Over the course of the evening, a room stuffed with increasingly rowdy viewers watched me navigate the uncanny depths of a cursed castle, my impotent hero pursued by shadow monsters. It scared the hell out of me. My friends, scaredy-cats all, loved it. Five Nights at Freddy’s found its fame in similar fashion: Let’s Play videos filled with freaked-out gamers, hamming up their reactions as they played for an audience of horror newbies, reveling in the bond-forming chemical reaction between vicariousness and schadenfreude. The film adaptation of the animatronic horrorshow gave the box office a jump scare, but it’s no surprise why: The franchise, and how its viewers/players interact with it, is a natural evolution of the guided rites of passage that have long welcomed initiates into the wider world of horror.

As our Tara Bennett wrote in her review of the adaptation, Five Nights at Freddy’s “is firmly an entry-level tween/teen horror film meant to woo that age demographic into the world of scares with some edge and blood.” She’s not alone in thinking so. BJ Colangelo makes the case that Five Nights at Freddy’s is both gateway horror and camp cinema. Agreed. Singin’, dancin’, killin’ Chuck E. Cheese parodies powered by the souls of murdered kids…that’s an idea ridiculous enough (and in poor enough taste) that I’m sure John Waters would find it hilarious. I’ll add to that: Five Nights at Freddy’s is gateway horror, camp cinema, and a multimedia blend that reminds us how the internet has influenced the youthful discovery of the impermissible.

When Five Nights at Freddy’s turned out to be a hit, my friend lamented that the movie sucked. Another replied that he was simply too old to appreciate it. He didn’t have the built-in mental overlay that so much of the film’s intended audience automatically applied to the film: A small implied box in the corner of the screen, with its webcam focused on the next generation of horror hosts. Having that association certainly won’t make the movie—an ouroboros of B-horror ideas, recycled into half-hearted videogame ideas and back again—any good, but it will make it more accessible for a certain crowd.

The series is angled towards the horror-curious, who found an entry point thanks to a degree of separation that’s long helped indoctrinate new converts to the genre. Now, though, the home of horror-by-proxy has shifted from staying up late for the midnight movie to browsing YouTube’s algorithm-driven database. There, whether you’re looking or not, those after gameplay videos can find thousands of Let’s Plays centered on horror. Many of these boast magnetic, superlative titles.

Markiplier, who made his bones hamming it up in Amnesia freak-out videos, named his first filmed foray into Five Nights at Freddy’s “SCARIEST GAME IN YEARS.”

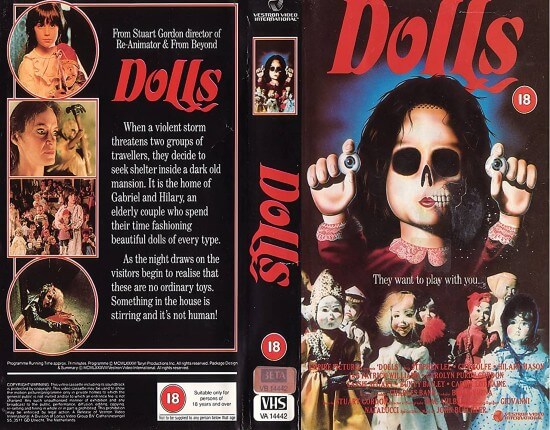

An eye-catching pullquote, a hint of danger—YouTube’s video store is stockpiled with the same taboos that’d have a kid trying to sneak an R-rated title past the clerk at a Blockbuster in the ‘90s. A goober making a cartoon face while pointing to a game screencap (with the game itself boasting a camp-horror reimagining of a kid’s birthday destination) can be just as tantalizing, and ultimately tame, as the box art of Stuart Gordon’s Dolls.

Obviously every kid is gonna try to rent this.

As those over-the-top facial expressions—wide-eyed and shocked—flooding your search results imply, these videos are hosted by players putting on a show. They lean into the genre’s trappings, playing up their reactions to match the theatricality at hand. And they found that the more they leaned in, the bigger their success.

The most viral games of the mid-2010s were horror games, games that were better as spectator sports. Like the schlockiest B-movies that still hold a fond place in your heart, being good was secondary to attracting an audience. Though riffing, explanation and theorizing are common Let’s Play practices across genres, horror games especially encourage this constant patter. It allows the player to make the game accessible, but also to compensate for fear felt by their audience and themselves—to stave off anxiety from the telegraphed sound cues and the inevitable, reflexive flinches that their errors will bring.

And when those errors come, the viewers love it. Scare compilations do numbers. We like to see someone freak out. You empathize with the terror, but from an empowering amount of distance. It’s the same logic as being more excited than scared when listening to an older sibling tell campfire stories or recount murderous urban legends. You’re just on the edge of the forbidden, brought there by something familiar.

Blending performance and participation, these Let’s Players (or Twitch streamers, for that matter) speak directly to their viewing audience, and in doing so create the same kind of characterized chaperone companionship as the bolo-tied Joe Bob Briggs or the OG Big Tiddy Goth GF Elvira. It’s camp, it’s connection, it’s an invitation for continued investment in the genre. As the box office for Five Nights at Freddy’s shows, those invitations were accepted en masse.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-