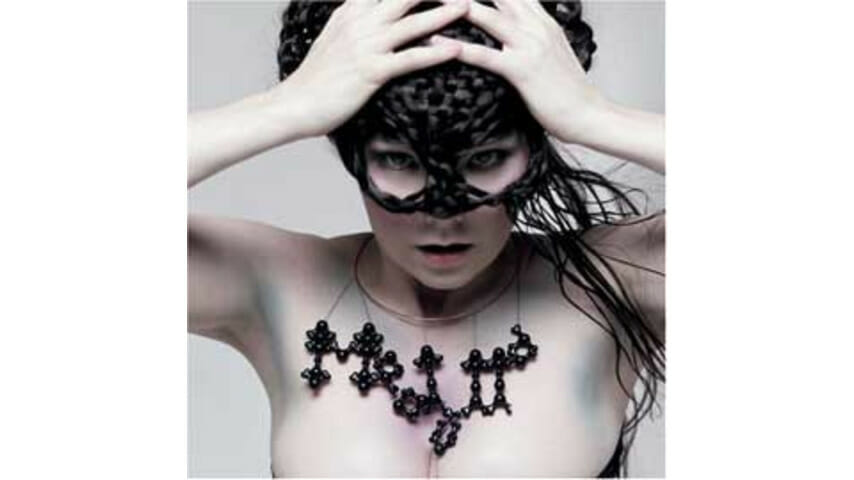

Björk: Björk – Medúlla

The reality that pop music—capable of accommodating endless permutations of the same essential form—has evolved in any meaningful fashion is wondrously strange. Even musicians considered textbook iconoclasts have conformed to the same instrumental formula as rock’s earliest purveyors. The Clash’s blistering political discontent incited a generation of British youth to question the establishment and its inherited value system, but the band’s arsenal—guitar, bass, drums—contented itself in the status quo. As if we needed proof: these are wonderfully inexhaustible building blocks.

Of course, along came the computer age, which further peeled back the ceiling on what was considered possible. The synthetic quality of modern life found yet another expression, another cathartic voice, in manufactured sound. All of a sudden, musicians who spent their acne-bothered pubescence indoors staring at computer monitors and resentfully butchering piano scales found themselves holding the power. Synthesized music emerged and musicians turned their focus toward its full-scale exploitation in the interest of patching together some novel approach.

For many artists, it wasn’t enough to revitalize rock’s established “classical” form; say, strumming a dismally familiar I-IV-V chord progression on a Rickenbacker electric guitar fed through a vintage VOX amplifier and reheating an old Beatles vocal melody—admittedly derivative, but seldom a bad recipe. True genius, as they understood it, meant defying convention. For instance, you might consider looping the flutter of a Scissor-tailed Hummingbird’s wings, recorded in zero gravity, through a metal pipe, and then screaming Portuguese obscenities over the mix until your vocal chords are shredded raw (keep in mind, a film documentary of this quest may prove more lucrative than the sound recording itself).

As we’ve learned from studying genetics, however, the overwhelming majority of DNA mutations prove maladaptive; they simply cause functional and developmental aberrations, ultimately speeding the affected organism’s demise. The same holds true in music. But then there are contemporary artists who, like Darwin’s finches before them, have mutated in ways that equipped them to survive beyond their allotted 15 minutes or so. Some have even altered music for the better—The Flaming Lips, David Byrne, Radiohead, Wilco. And, of course, Björk, whose newest creation, Medúlla, sprouted legs and crawled ashore in late August.

For the uninitiated listener, Medúlla appears to have hitchhiked its way 300 million light years across space to earth aboard a hurling meteor from an infinitesimally-distant spiral galaxy called Zentron-IV, whose snow-covered planets house 18-headed spider-like organisms who survive by drinking interstellar dust through lidless silver eyes.

“Ancestors” (easily the most bizarre cut on Medúlla) opens with a series of exaggerated sighs, the kind of melodramatic vocalizations with which choirs or drama groups often warm up their voices prior to a performance. A little odd, perhaps, but innocuous enough from a listening standpoint, considering the sighs are accompanied by measured piano lines. But as the four-minute track unfolds, the listless sigh splits amoeba-like into a chorus of similar female voices which alternately sing unintelligible words or moan distractedly. The keening sigh—our protagonist, if you will—eventually ramps up into a hyperventilated gasp, rendered even more unsettling by the introduction of a (computerized, I pray) bestial grunt that can only be described as a warthog on the verge of climax.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-