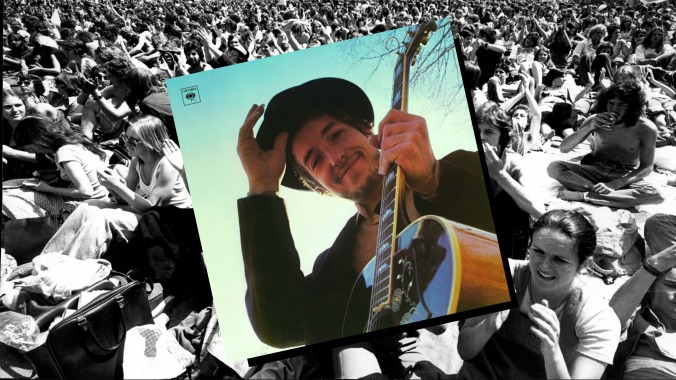

Time Capsule: Bob Dylan, Nashville Skyline

Released 55 years ago, Dylan’s ninth studio album is not a radical album, but a domestic and deeply humane pocket of love songs that rarely linger. He may not be gospelizing American strife, the Civil Rights Movement or impending nuclear war, but his lyricism remains profound and his sincerity glows in the context of the great country band playing behind him.

Nashville Skyline is, depending on the day, Bob Dylan’s greatest feat. Here is the best songwriter of his generation, barely four years removed from turning the folk world inside out with his “going electric” performance at the Newport Folk Festival in 1965, yet again transforming on tape. Putting out the Bringing It All Back Home, Highway 61 Revisited and Blonde on Blonde triplicate in a two-year span remains one of the most important three-album runs in the history of popular music, but Dylan turned his focus towards a rootsy, agrarian, anti-trend record in John Wesley Harding in 1967—releasing it in a year met by a reverie of psychedelic, audacious material from the Beatles (Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band), Jimi Hendrix (Are You Experienced?) and the Doors (Strange Days), Cream (Disraeli Gears) and Love (Forever Changes). John Wesley Harding was experimental, sure, but the album was placid and swiftly disinterested in existing in the context of whatever counterculture had become the world’s precedent.

Dylan had spoken about making a country album in Nashville as early as 1965 in a conversation with Johnny Cash. The thought was that Cash would produce the album and capture his friend ensconced in the “Nashville Sound” that had grabbed country music a decade earlier, defining the likes of Chet Atkins, Patsy Cline, Don Gibson, Jim Reeves and the Anita Kerr Quartet. The 1960s in the South were not immune to the British Invasion’s influence, as country music reckoned with the deaths of Reeves and Cline by adopting a pop-inspired, “countrypolitan” get-up that rivaled the Bakersfield Sound spilling out of California. But the sessions between Cash and Dylan never materialized; Dylan was fully immersed in making Highway 61 Revisited and “Like a Rolling Stone,” an album and song both so generational that they remain immovable, tectonic pieces of an American landscape mid-identity crisis.

Nashville Skyline is the antithesis of the Bob Dylan we’ve long considered to be the “Voice of Protest.” It’s nothing like The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan or The Times They Are A-Changin’ or Another Side of Bob Dylan. In the year leading up to its release, the political climate in America had unraveled into a dystopia: Martin Luther King, Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy were both assassinated; the Vietnam War, under the guidance of the recently elected Richard Nixon, entered an unfathomably bleak and inescapable period; riots broke out at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago. Dylan, once a laureate of political folk song, had all but abandoned his hot-button, finger-on-the-pulse commentary and embraced something far more idyllic and cliché. Instead, it’s an “I’m in love!” record that exists perpendicular to the hellish mortality colored in multitudes on the Nashville Skyline predecessors.

I wouldn’t say that Nashville Skyline is a radical album, because I don’t measure the merits of dissent by stylistic changes. Bob Dylan quitting smoking and re-emerging with a softer, crooning tenor is not some remarkable act—especially not now, as we have lived through about five or six of his different vocal epochs. But what I will say about Nashville Skyline is that it is simple—basic, I’d even argue—domestic and deeply, deeply humane. It is a record full of love songs and utopian advances. And, for somebody like Dylan, whose mystery precedes his own vernacular, he sounds alien on Nashville Skyline. He sounds happy and, perhaps, at rest on songs that demand nothing of their listeners beyond holding and being held. He may not be gospelizing American strife, the Civil Rights Movement or impending nuclear war here, but his lyricism remains profound; “Whatever colors you have in your mind, I’ll show them to you and you’ll see them shine” is one of his greatest images, yet it comes and goes like a crack of wind.

And that’s because these 10 songs rarely linger. It takes 27 minutes to digest the album, and its longest entry is its opener—the Johnny Cash-assisted re-recording of the Freewheelin’ cut “Girl from the North Country,” clocking in at three minutes and 41 seconds. Five tracks are less than two-and-a-half-minutes long. Yet the decor of Nashville Skyline is anything but minimal; the band Dylan assembled for the sessions—Norman Blake, Fred Carter Jr., Charlie McCoy, Charlie Daniels, Bob Wilson, Kenneth A. Buttrey and Pete Drake—was a tight collective of country music’s then-finest making some of the genre’s handsomest textures, and Bob Wootton, Marshall Grant and W.S. Holland made one-off appearances on “Girl from the North Country” to complete the outfit.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-