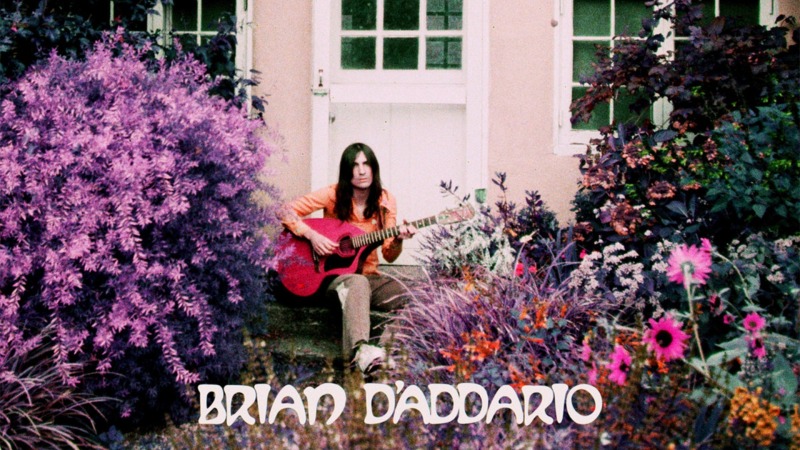

Brian D’Addario’s First Solo LP Till the Morning is Beautiful, But Nothing New

While this is a solo record, Brian’s younger brother, Michael, co-produced the album and sings on five out of the 11 songs.

Brian and Michael D’Addario dropped their fifth album as the Lemon Twigs, A Dream Is All We Know, only last year, so it feels like a quick turnaround for the former to release his debut solo record. However, most of the songs on Brian’s album Till the Morning have been floating around for some time now, just waiting for the right home. “These were tunes that piled up over the years but when I started putting the album together, it really hung together musically and thematically. It’s country baroque,” Brian explains in a press release. And while there are slide guitar moments here and there, as well as some Carter Family inspiration, Till the Morning still fits decidedly in the Lemon Twigs’ velvety, carefully crafted ‘60s-style pop sound.

That sonic consistency is no surprise considering that Brian’s younger brother, Michael, co-produced the album and sings on five out of the 11 tracks. Even when Brian’s operating on his own, those songs still feel like B-sides from a forgotten Lemon Twigs LP (which in turn sound like something that was unearthed from the Beatles or the Beach Boys’ storage units). “Till the Morning”—a Brian-only affair, with Paul D. Millar engineering—is a warm, jaunty springtime air that channels Simon and Garfunkel and includes the standout line “If I knew where my mind went tucked beneath your thighs / I’d go there more often.” The best track on the album is “Company,” which starts with straightforward piano flourishes and Brian’s voice, until strangely orchestral electric guitar and Moog synths traipse in, buzzing furiously like a kicked hive.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-